Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-09-2015, 05:38 PM

(This post was last modified: 02-09-2015, 09:39 PM by waynetalger.)

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Flannagan

(02-09-2015, 08:50 AM)aprirr Wrote: This is a great thread! We only have one T-206 in our collection: Stoney McGlynn. Played for the minor league Brewers and moved to our hometown to work in the aluminum factory here after his baseball days were over. I drive past the cemetery where he is buried every day on my way to work.

Man that is cool I am waiting to see if any are buried around my area or maybe from a neighboring home town where he grew up

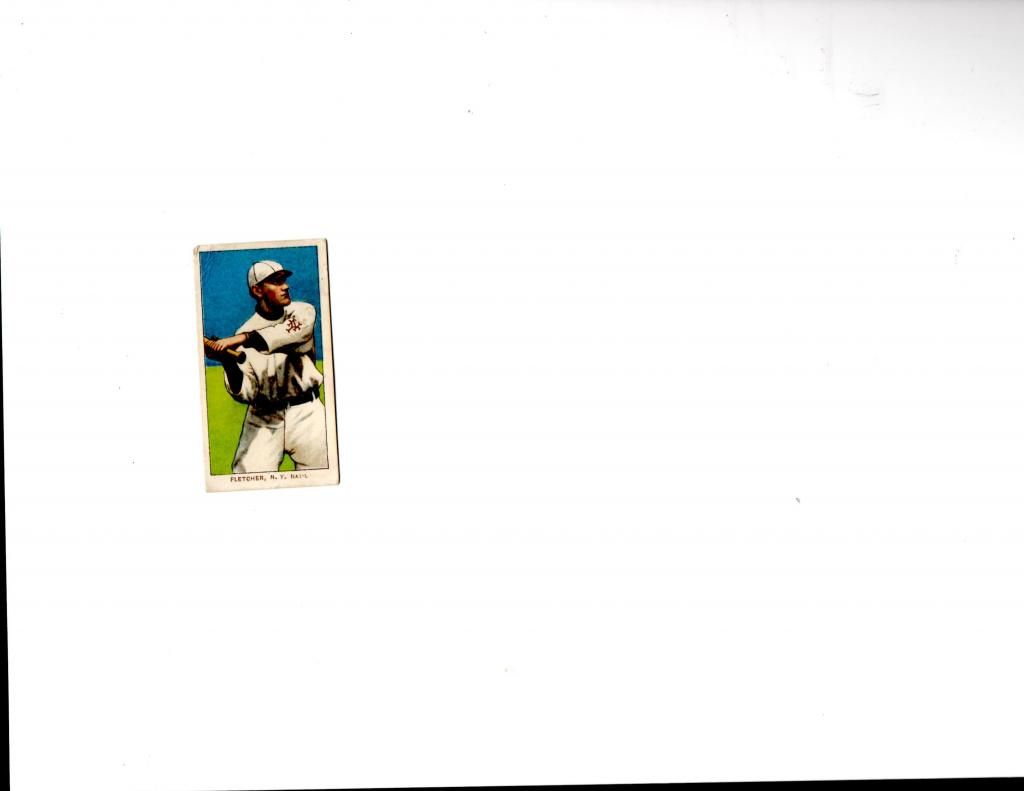

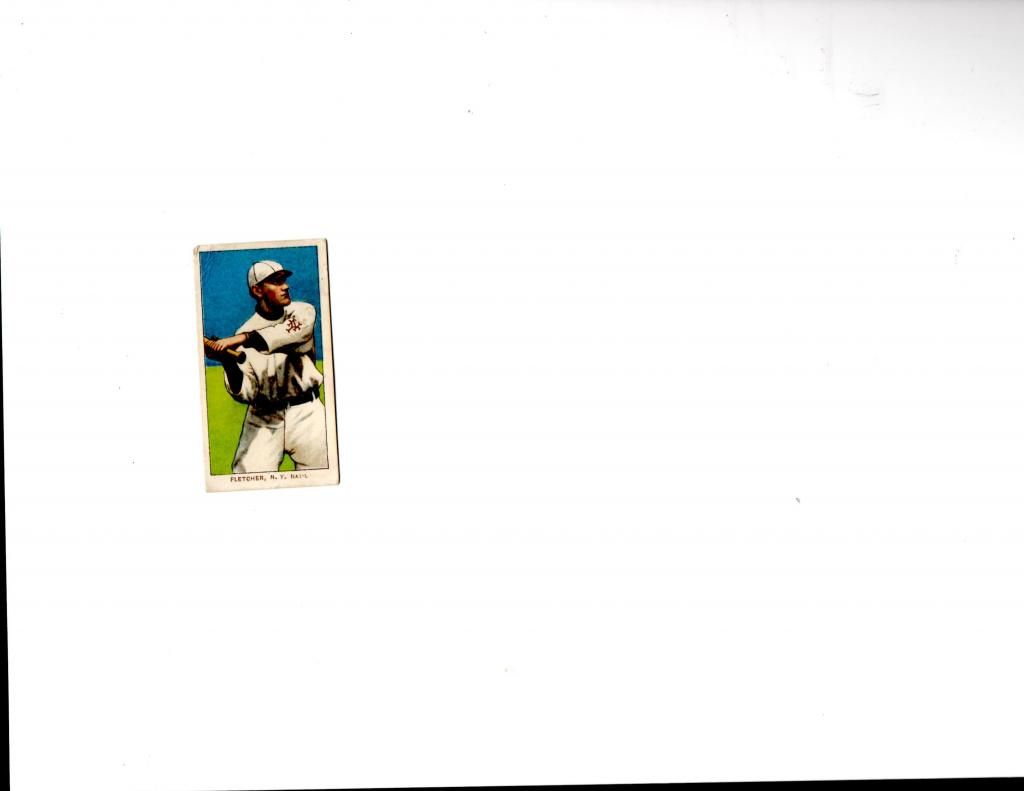

Art Fletcher

Arthur Fletcher (January 5, 1885 – February 6, 1950) was an American shortstop, manager and coach in Major League Baseball. Fletcher was associated with two New York City baseball dynasties: the Giants of John McGraw as a player; and the Yankees of Miller Huggins and Joe McCarthy as a coach

Born in Collinsville, Illinois, Fletcher came to the Giants in 1909 and became the club's regular shortstop two years later. He played in four World Series while performing for McGraw (1911, 1912, 1913 and 1917). Traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in the midst of the 1920 season, he retired after the 1922 campaign with 1,534 hits and a .277 batting average. He batted and threw right-handed. Fletcher is the Giants' career leader in being hit by pitches (132) and ranks 21st on the MLB career list (141) for the same statistic.

In 1923 he replaced Kaiser Wilhelm as manager of the seventh-place Phillies and led the club through four losing seasons, bookended by last-place finishes in 1923 and 1926. In October 1926, he was replaced by Stuffy McInnis.

Fletcher then began a 19-year tenure (1927–45) as a coach for the Yankees, where, beginning with the 1927 team, he would participate on ten American League pennant winners and nine World Series champions. On a tragic note, he served as the acting manager of Yankees for the last 11 games of the 1929 season when Huggins was fatally stricken with erysipelas. He won six of those 11 games, to compile a career major league managing record of 237-383 (.382).

Fletcher retired after the 1945 season and died from a heart attack in 1950 in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 65.

Arthur Fletcher Field, located in Collinsville, Illinois, is named for him. The field is home of the Collinsville High School Kahoks, the Collinsville Miners American Legion team, and the Collinsville Herr Travelers junior legion team

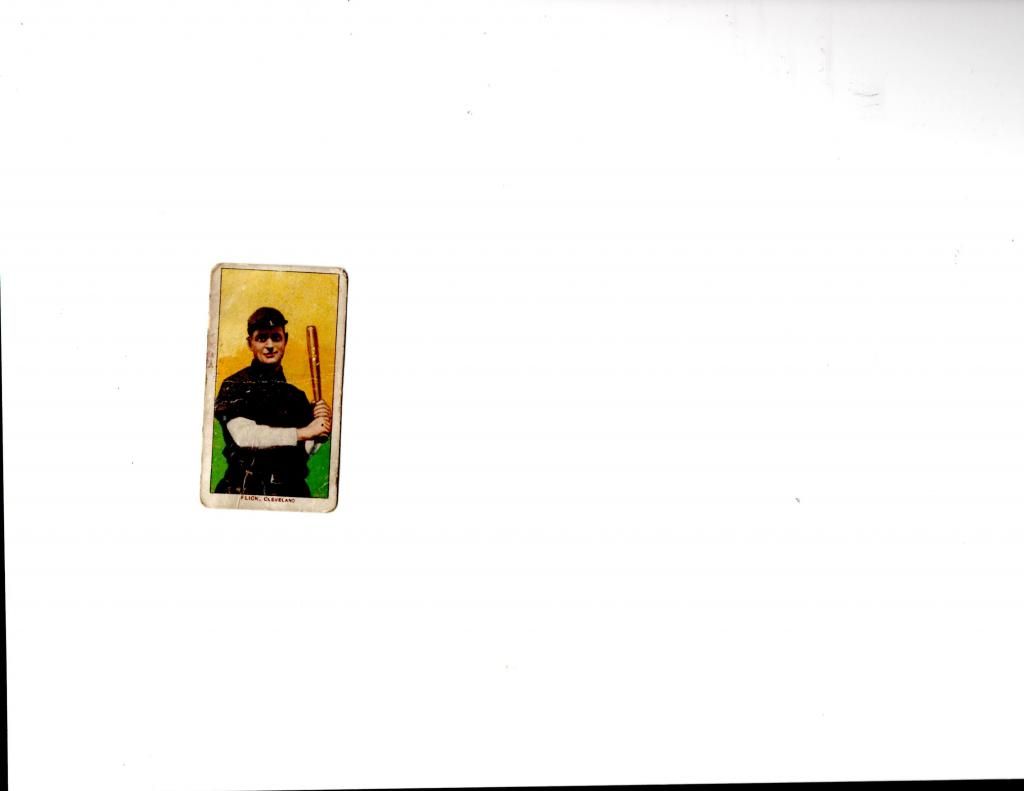

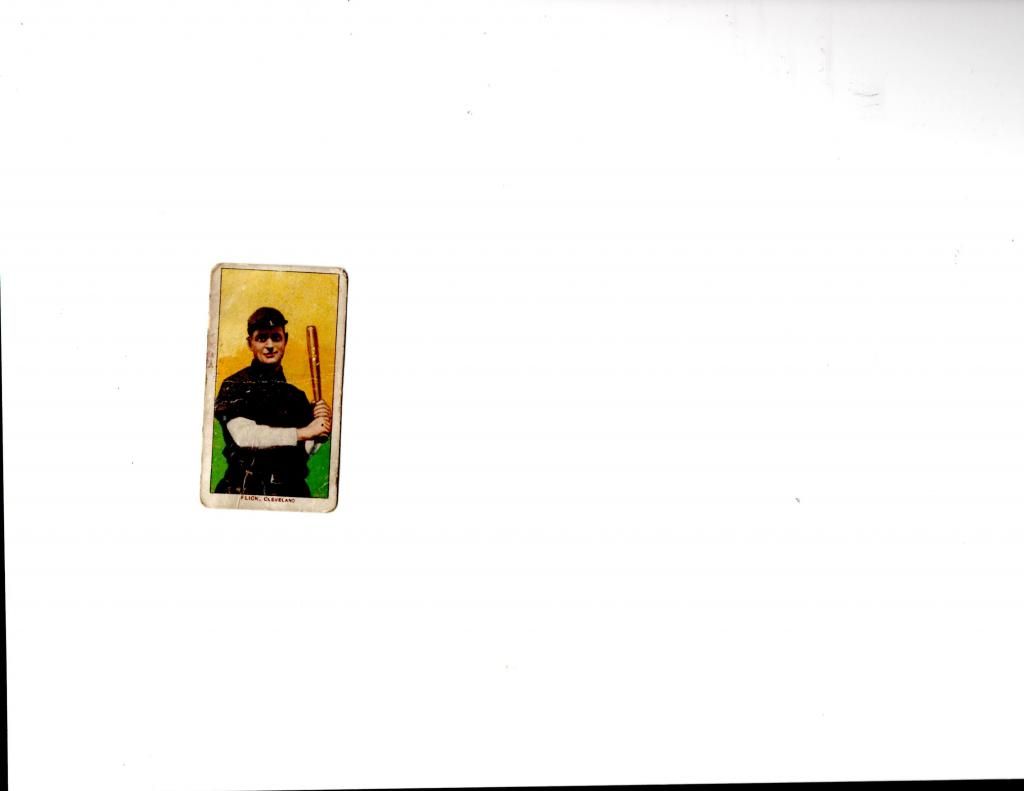

Elmer Flick (oldest living person inducted in the HOF)

Elmer Harrison Flick (January 11, 1876 – January 9, 1971) was an American professional baseball outfielder who played in Major League Baseball from 1898 until 1910 for the Philadelphia Phillies, Philadelphia Athletics, and Cleveland Bronchos/Naps.

Flick began his career in semi-professional baseball and played in minor league baseball for two years. He was noticed by George Stallings, the manager of the Phillies, who signed Flick as a reserve outfielder. Flick was pressed into a starting role in 1898 when an injury forced another player to retire. He excelled as a starter. Flick jumped to the Athletics in 1902, but an court injunction prevented him from playing in Pennsylvania. He joined the Naps, where he continued to play for the remainder of his major league career, which was curtailed by a stomach ailment.

Flick was known predominantly for his solid batting and speed. He led the National League in runs batted in in 1900, and led the American League in stolen bases in 1904 and 1906, and in batting average in 1905. Flick was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963.

Flick was born on January 11, 1876, the third of five children of Zachary and Mary Flick, on the family farm in Bedford, Ohio.[1] His father was a farmer and mechanic who had served in the American Civil War.[2] Flick attended Bedford High School, where he played catcher on the school's baseball team.[3] He also played American football, wrestled, and boxed.[2]

Flick entered semi-professional baseball by chance. When he was 15 years old, he was at a train station to support the local baseball team as it left for a road trip. Only eight of the team's players showed up at the station, so Flick was recruited to go on the trip with the team.[1] Though Flick did not have a uniform or shoes, he hit well in both games of the doubleheader, though Bedford lost both games. He joined the Bedford team on a regular basis.[2]

Returning to Bedford, Flick hunted, raised horses, built buildings, and became involved in selling real estate. He also scouted for Cleveland.[2] Only four 19th century baseball players, including Flick, were still alive in 1970. In his later years, Flick still answered requests for autographs from his fans. Proud of his longevity, Flick often completed autographs by writing the date and his age above or underneath his signature.[29]

Flick was married to Rosa Ella (née Gates). The couple had five daughters.[2] Flick died in his hometown of Bedford in 1971, at the age of 94, of congestive heart failure. He also suffered from mycosis fungoides.[2]

When Cobb died in 1961, stories written about him mentioned the attempted trade between Cleveland and Detroit, which revived interest in Flick.[2] Flick was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963 after being unanimously elected by the Veterans Committee (VC).[30] When he received the call from Branch Rickey that he had been selected, Flick did not believe Rickey at first. He said that he did not even realize that he was being considered for election at the time.[31] Flick's family had to convince him that the call was real. He was the oldest living inductee in Hall of Fame history. At his induction, the 87-year-old Flick said, "This is a bigger day than I've ever had before. I'm not going to find the words to explain how I feel."[32]

Subsequent to his induction, writers have questioned the validity of Flick's Hall of Fame membership. James Vail characterized Flick and three other Hall of Famers as "some of the most dubious VC choices ever".[33] David Fleitz wrote that Rickey's influence on the Veterans Committee led to Flick's election, as Rickey was the only committee member who had seen Flick play.[32] Author Robert E. Kelly pointed out that Flick's career was relatively short and that stronger candidates from Flick's era (such as Sherry Magee) had not been inducted.[34]

Flick was enshrined in the Greater Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame in 1977, and the Ohio Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987. A statue of Flick's likeness was created to be placed in Bedford;[35] it was funded by donations and was dedicated in September 2013. Mike Hargrove was among the baseball figures who attended the ceremony.[36]

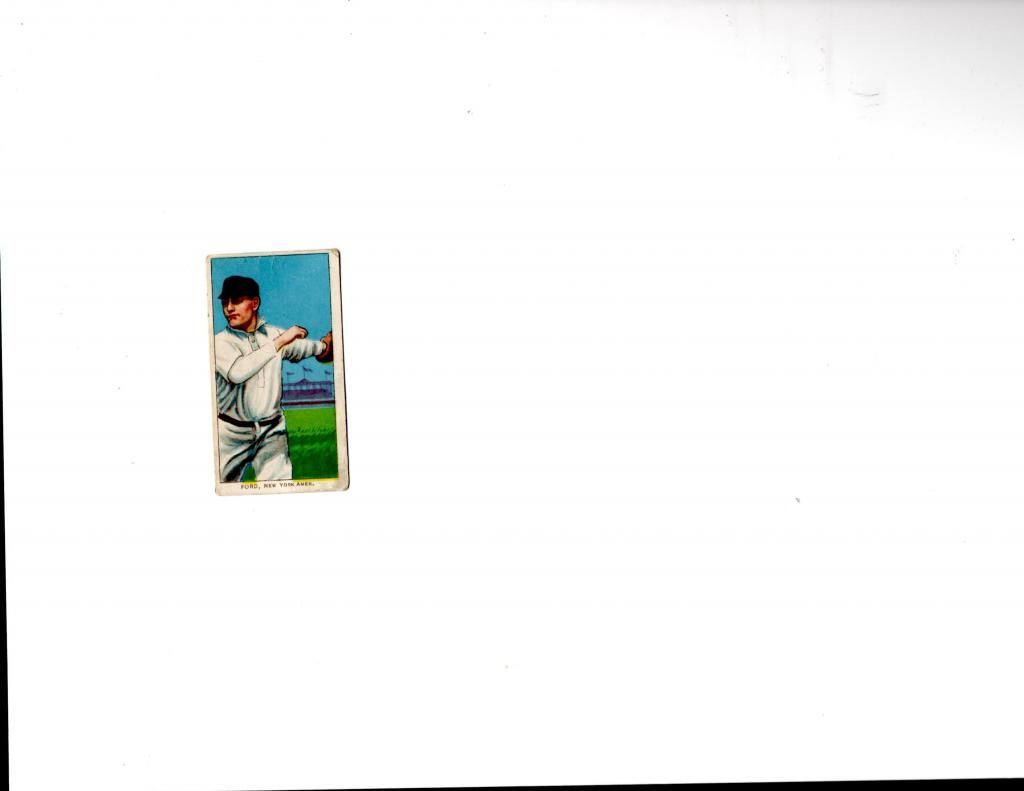

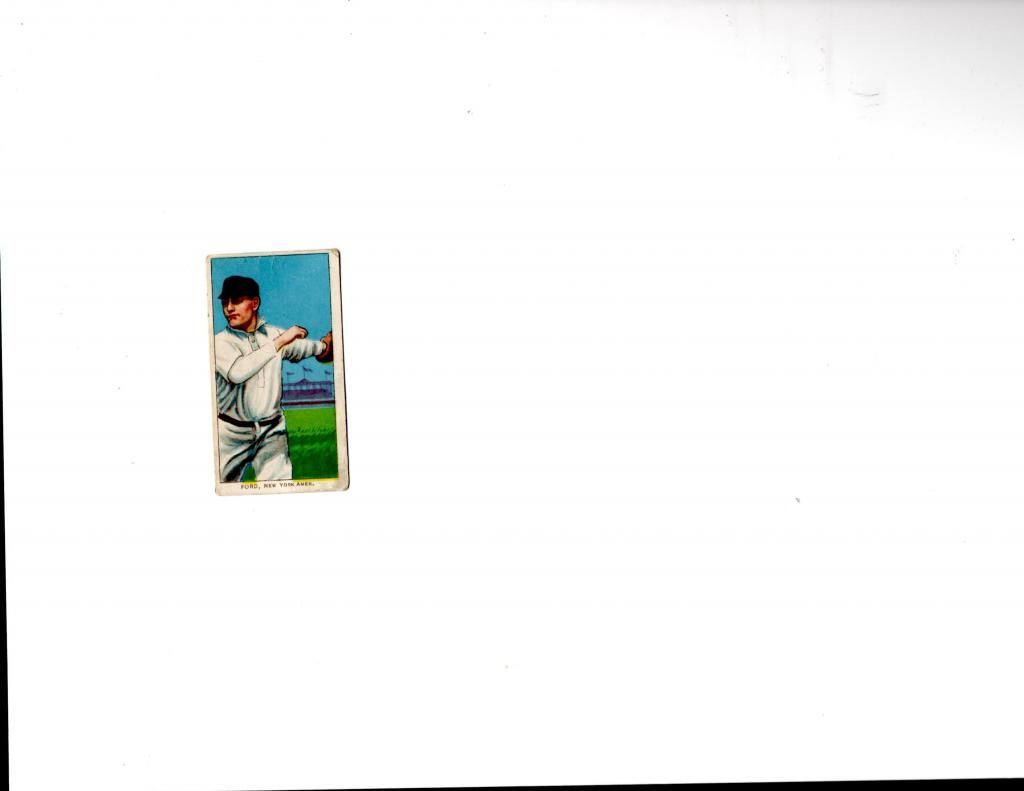

Russ Ford

Russell William Ford (April 25, 1883 – January 24, 1960) was a Major League Baseball pitcher during the dead-ball era of the early 1900s.

Ford is best known as the creator of the "emery" or "scuff" ball, a pitch that was thrown with a ball that had been scuffed with a piece of emery. Ford came across the "scuff ball" by accident when playing for the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association in 1908.[1] When pitching under a grandstand due to rain, Ford accidentally threw a ball into a wooden upright, marking the surface.[1] Ford threw another pitch with the damaged ball, and noticed how it curved more than previous pitches.[1]

Ford won 26 games in his rookie season of 1910, becoming only the third player in major league history to win 20 games and strike out at least 200 batters in his first season (Christy Mathewson and Grover Cleveland Alexander are the others).

His pitch selection included the famed scuff/emery ball, a spitball, fastball, and knuckle ball.[2]

Ford was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1989 and into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame and Museum in 2002

Russ' brother, Gene Ford, also played in the major leagues. Gene pitched in seven games for the Detroit Tigers in 1905.

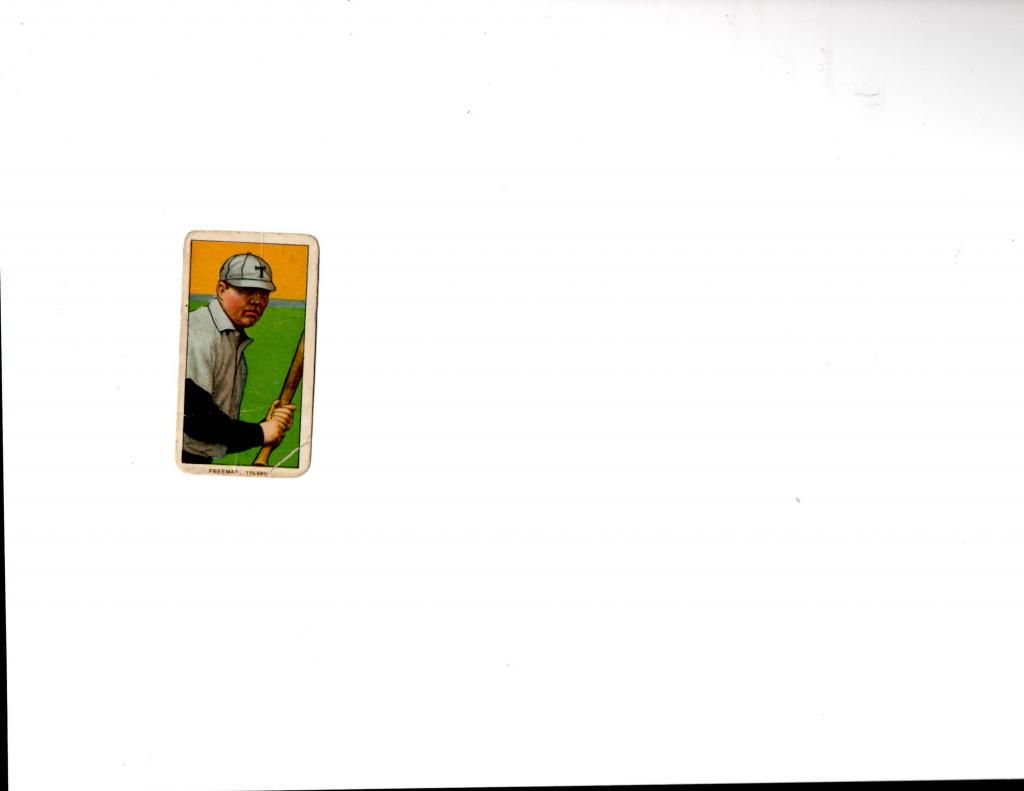

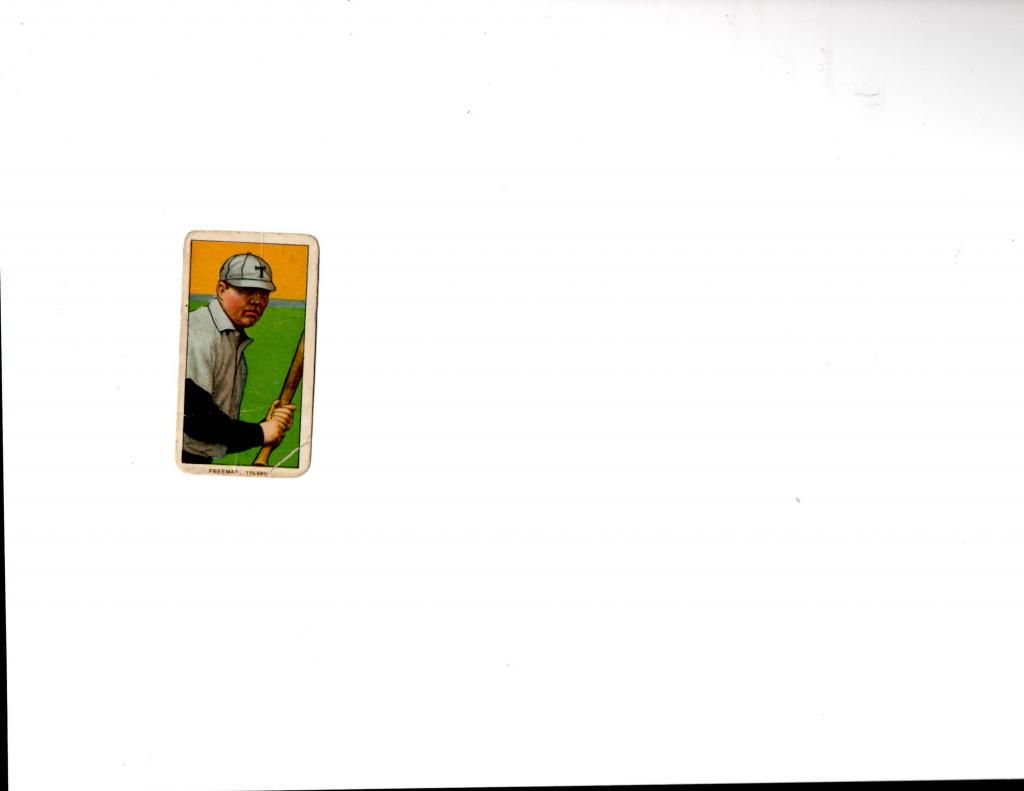

Jerry Freeman

Frank Ellsworth "Jerry" Freeman (December 26, 1879 – September 30, 1952) was a first baseman in Major League Baseball. Nicknamed "Buck", he played for the Washington Senators from 1908 to 1909.

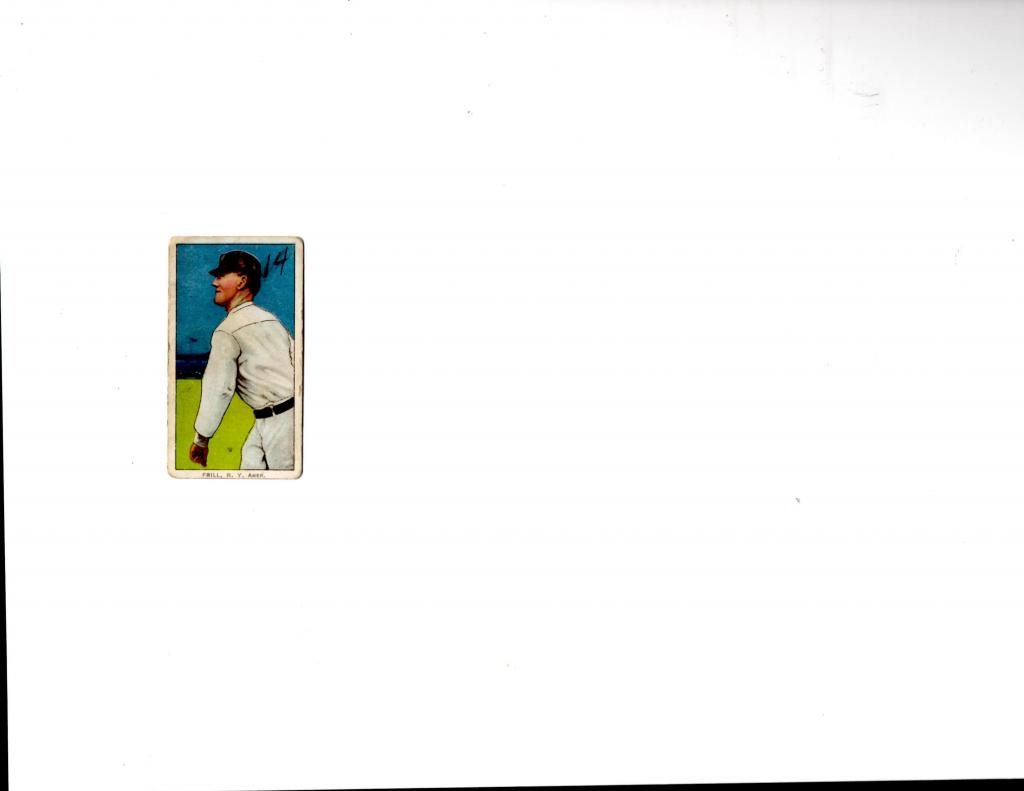

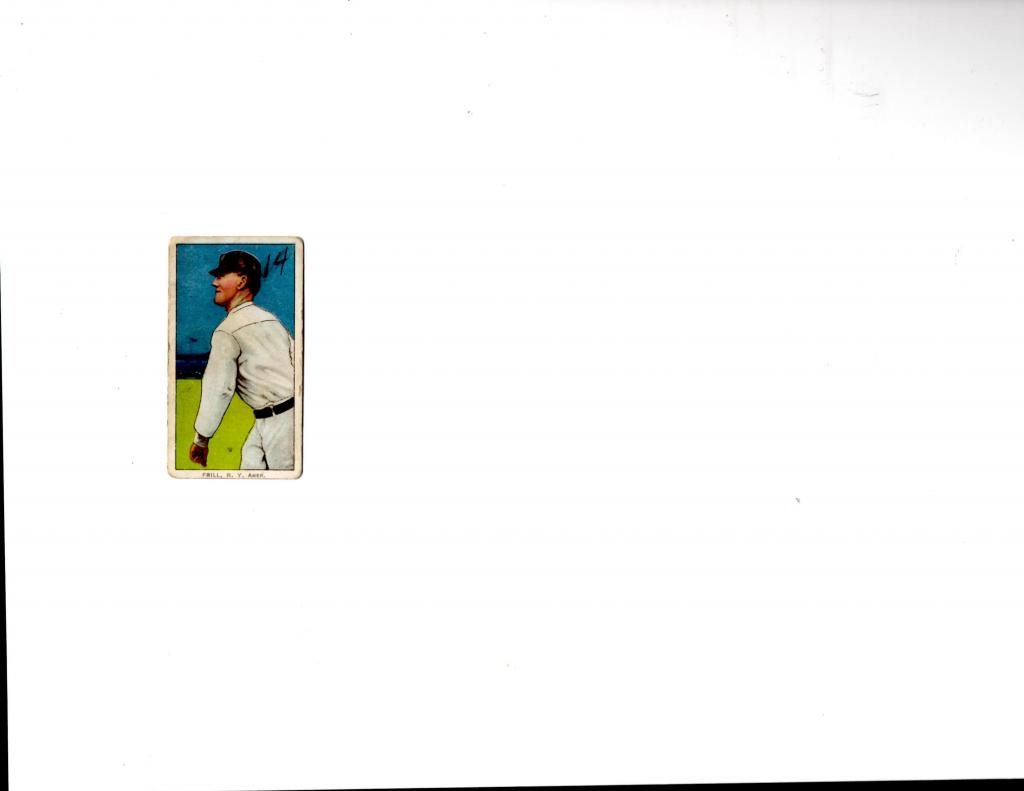

John Frill

John Edmond Frill (April 3, 1879 – September 28, 1918) was a Major League Baseball pitcher who played in 1910 and 1912 with the New York Highlanders, St. Louis Browns and the Cincinnati Reds. He batted right and threw left-handed.

He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and died in Westerly, Rhode Island.

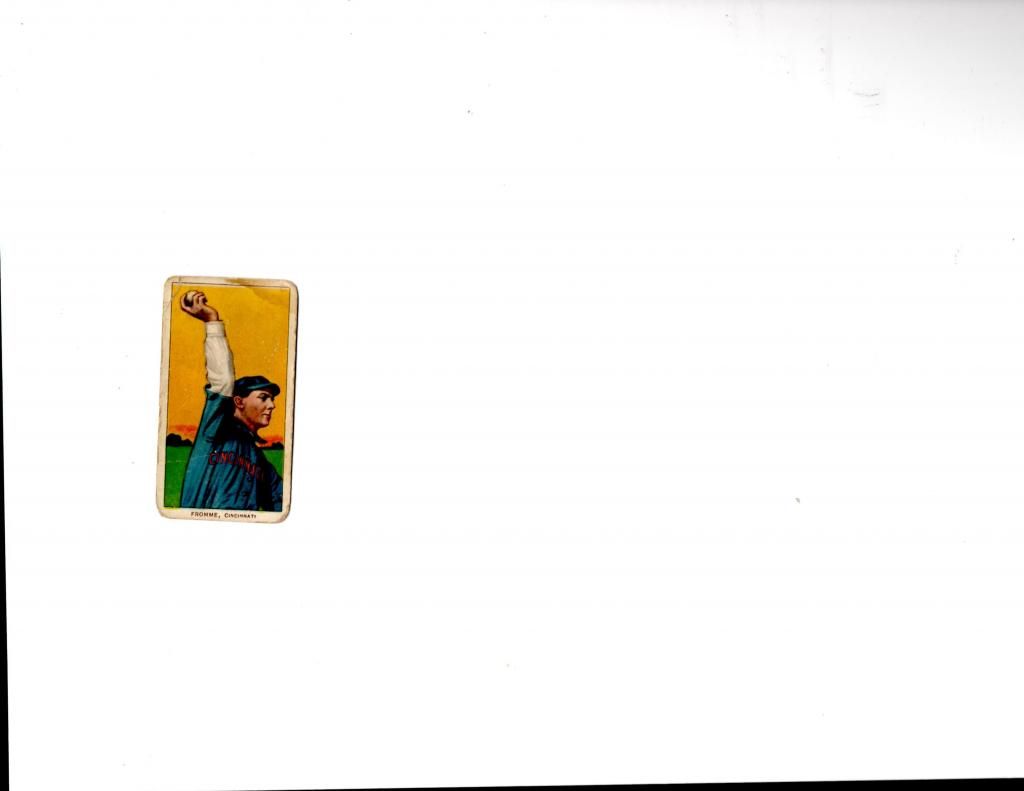

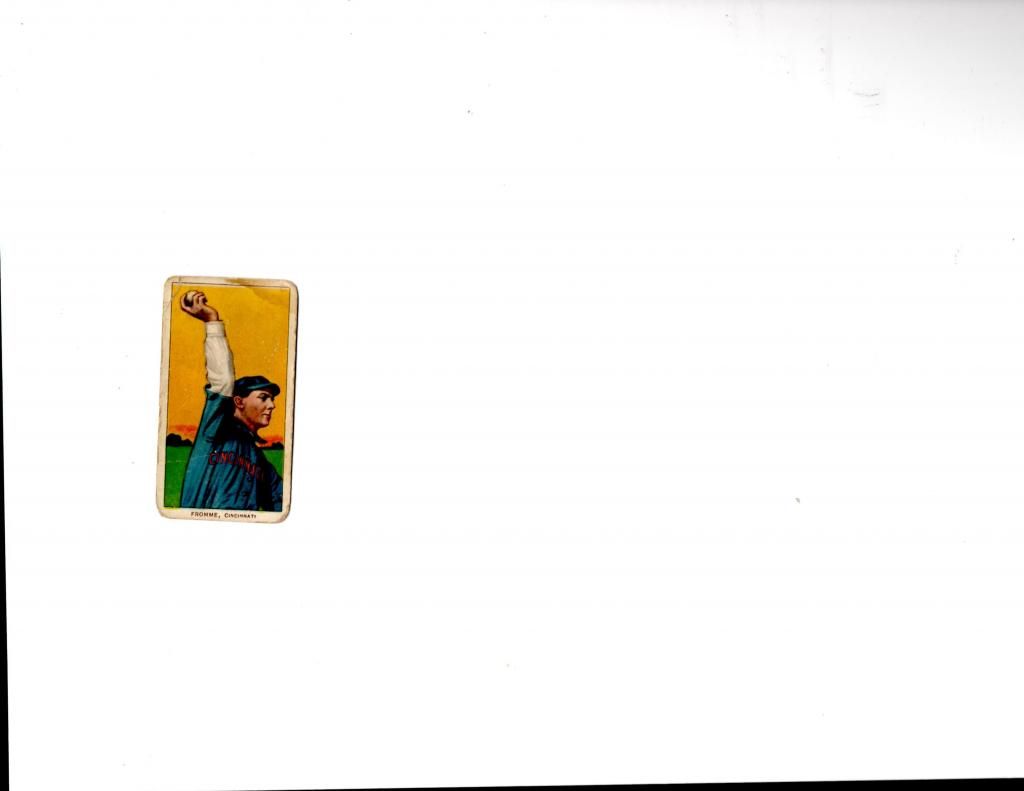

Art Fromme

Arthur Henry Fromme (September 3, 1883 in Quincy, Illinois – August 24, 1956 in Los Angeles, California), was a professional baseball player who pitched in the Major Leagues from 1906-1915. He played for the St. Louis Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants.

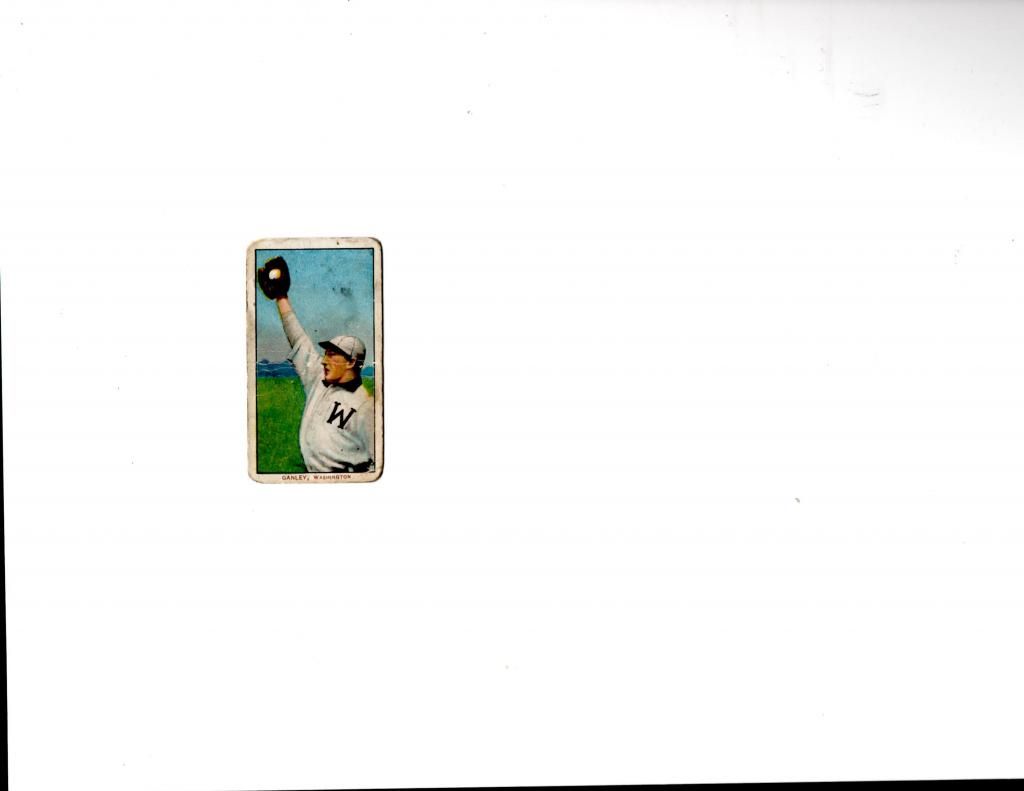

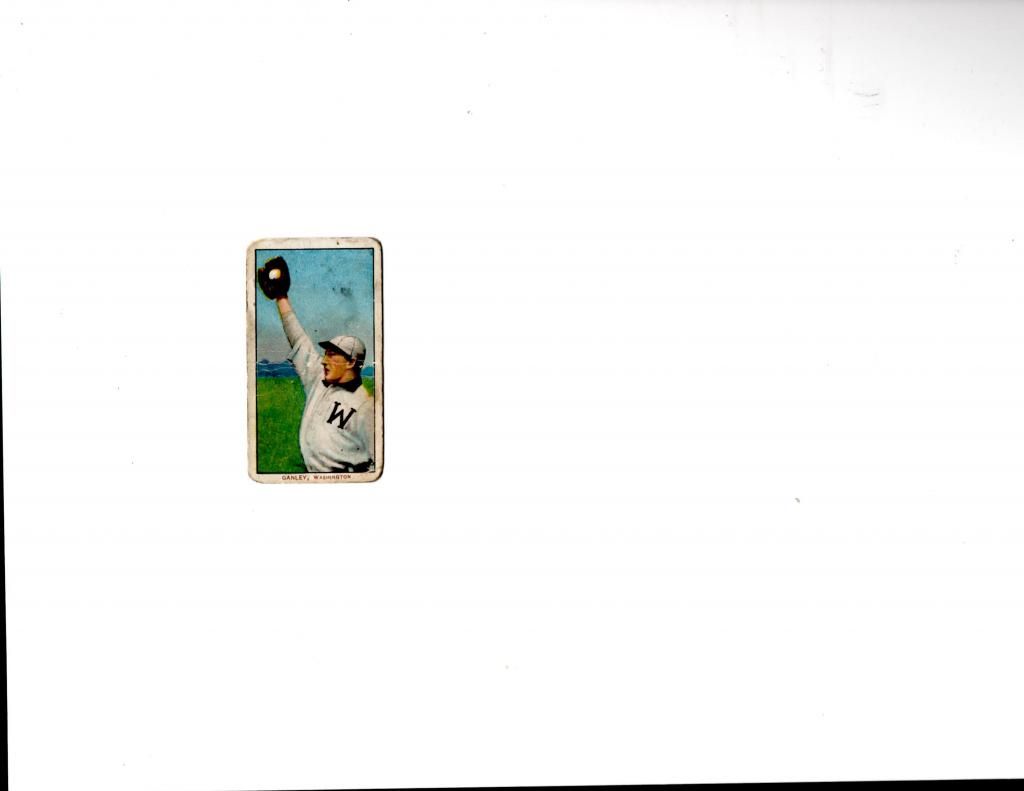

Bob Ganley

Robert Stephen Ganley (April 23, 1875 in Lowell, Massachusetts – October 9, 1945 in Lowell, Massachusetts), was a Major League Baseball player who played outfielder from 1905-1909. He would play for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Philadelphia Athletics, and Washington Senators.

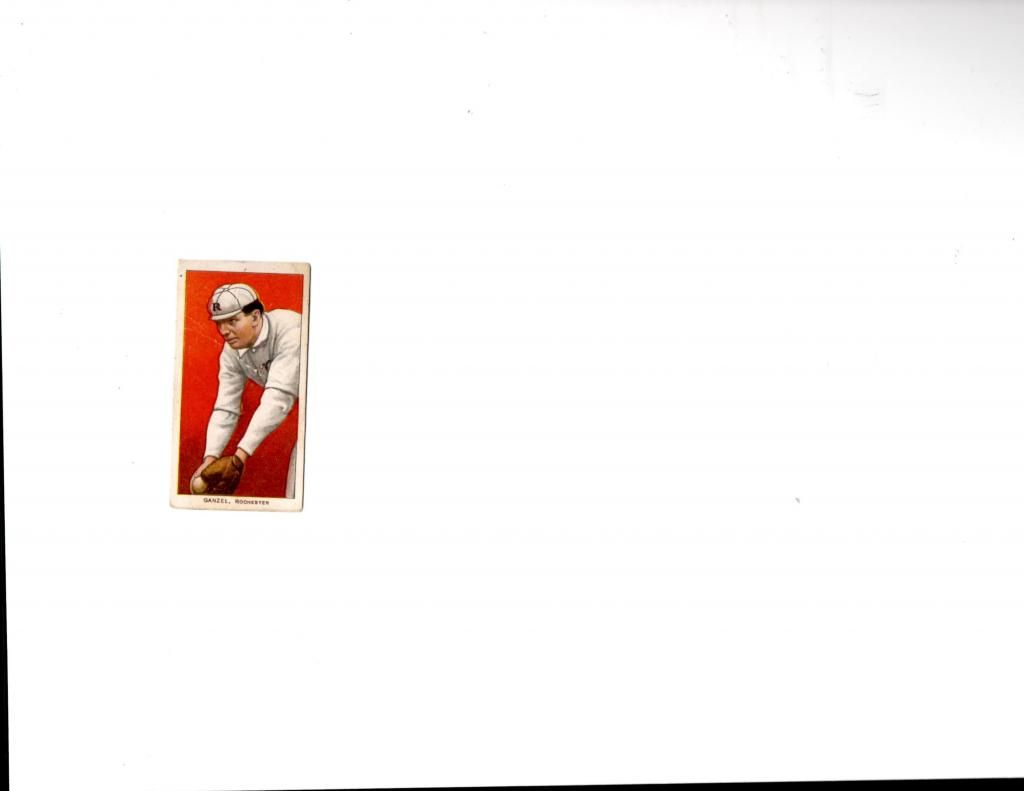

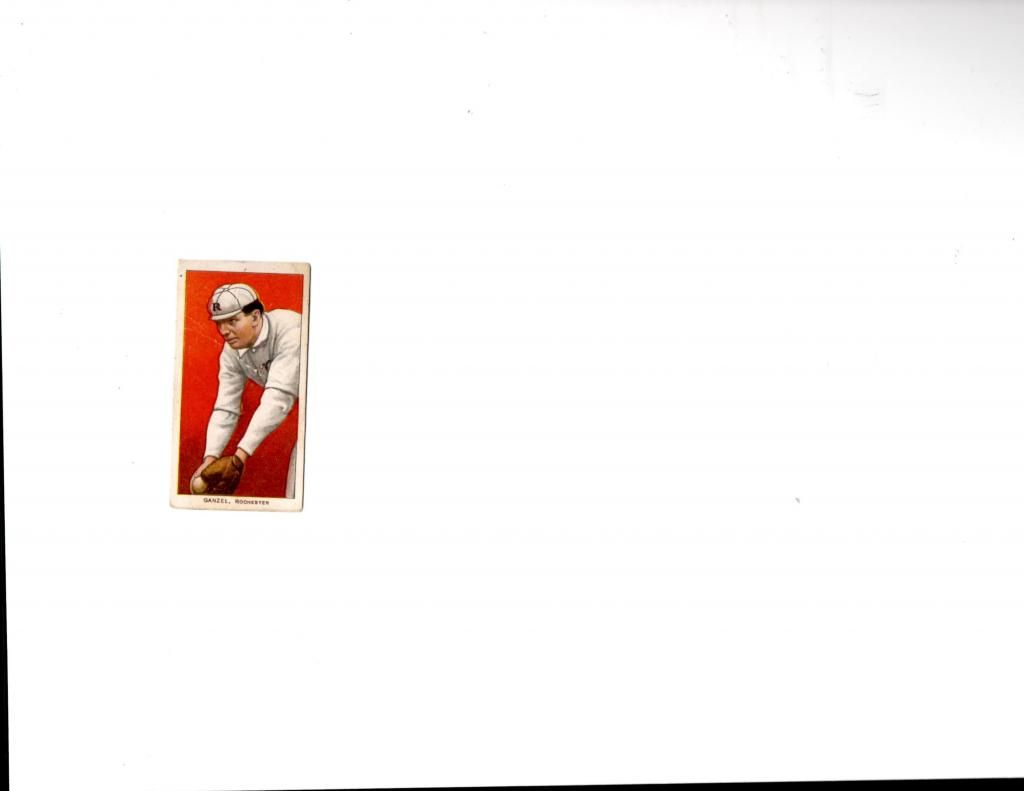

John Ganzel ( Hit the Yankees first Home Run)

John Henry Ganzel (April 7, 1874 – January 14, 1959) was an American first baseman and manager in Major League Baseball. Ganzel batted and threw right-handed. He played with the Pittsburgh Pirates (1898), Chicago Cubs (1900), New York Giants (1902) New York Highlanders (1903–1904) and the Cincinnati Reds (1907–1908). Ganzel managed the Reds in 1908 and the Federal League's Brooklyn Tip-Tops in 1915. He hit the first ever Yankee home run on May 11, 1903.[1]

A native of Kalamazoo, Michigan, Ganzel came from a family of baseball men. His brother, Charlie, was a catcher who played with the St. Paul Saints, Philadelphia Phillies, Detroit Wolverines and Boston Beaneaters during 14 seasons, and his nephew Babe Ganzel was an outfielder for the Washington Senators. Two brothers and two nephews also played in the minor leagues.

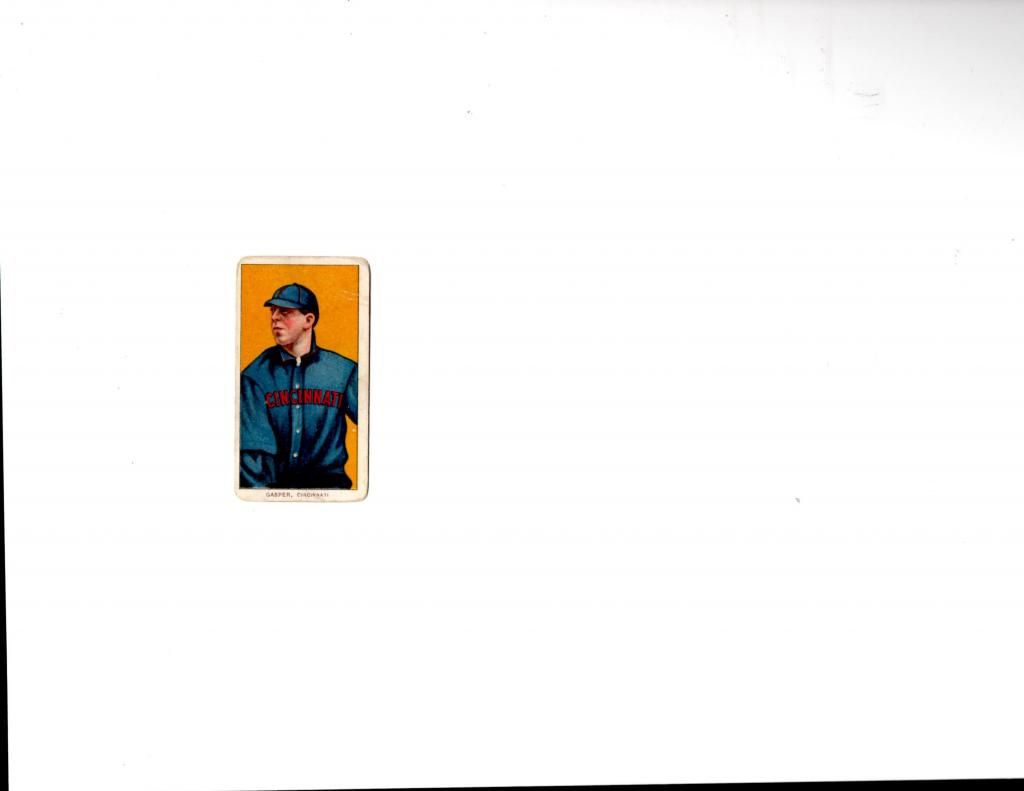

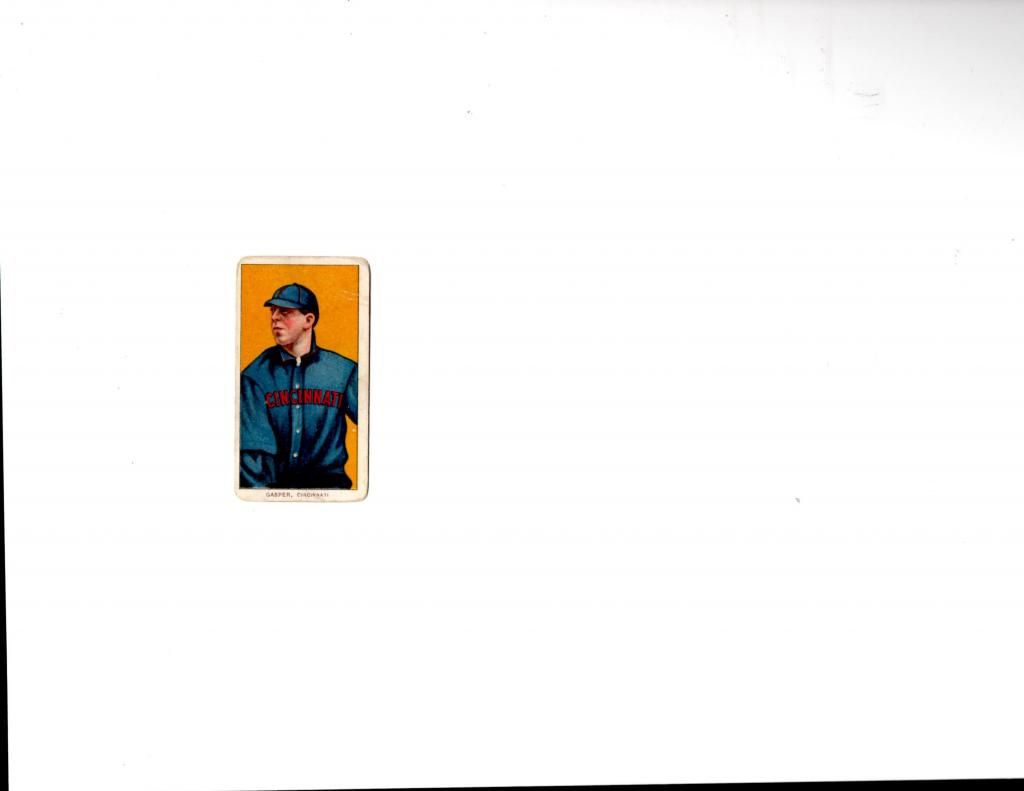

Harry Gasper

Harry Lambert Gaspar (April 28, 1883 – May 14, 1940) was a professional baseball player. He was a right-handed pitcher over parts of four seasons (1909–1912) with the Cincinnati Reds. For his career, he compiled an 46–48 record in 143 appearances, with an 2.69 earned run average and 228 strikeouts.

Gaspar was born in Kingsley, Iowa, and later died in Orange, California at the age of 57.

Rube Geyer

Jacob Bowman "Rube" Geyer (March 26, 1884 – October 12, 1962) was a Major League Baseball pitcher who played for the St. Louis Cardinals from 1910 to 1913.[1] His key pitch was the drop ball

![[Image: roughdraft_edited-1.jpg]](http://i51.photobucket.com/albums/f354/blayneroessler/roughdraft_edited-1.jpg)

Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-10-2015, 10:34 PM

(This post was last modified: 02-12-2015, 07:33 PM by waynetalger.)

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Geyer

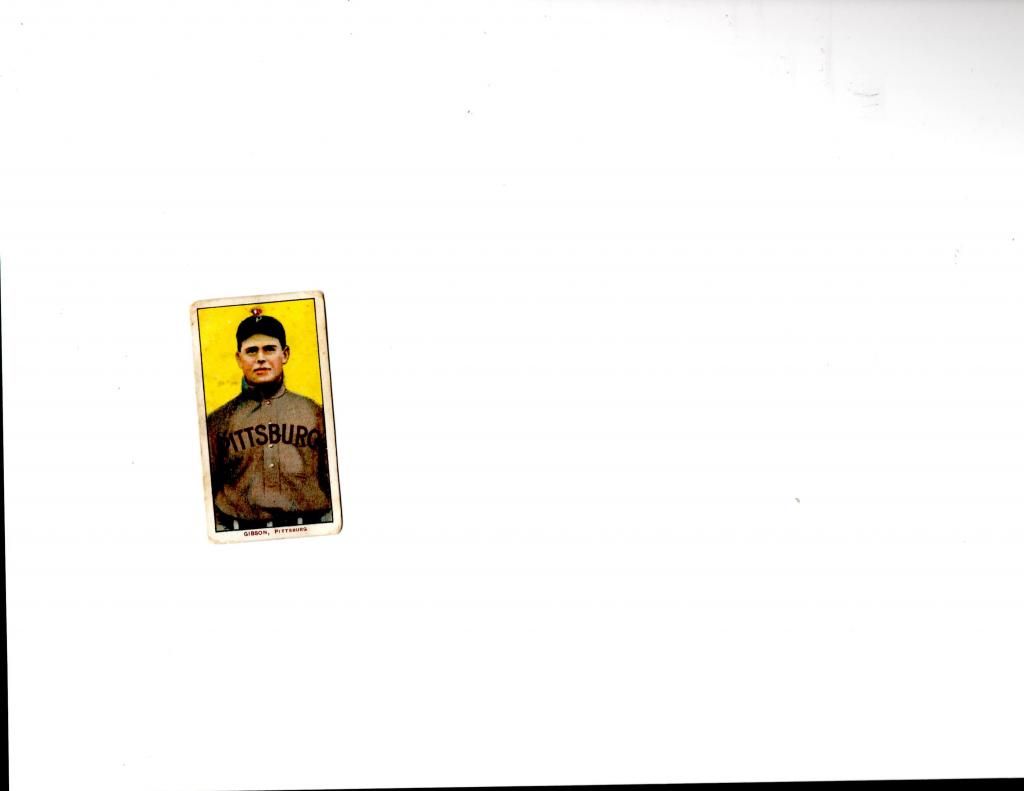

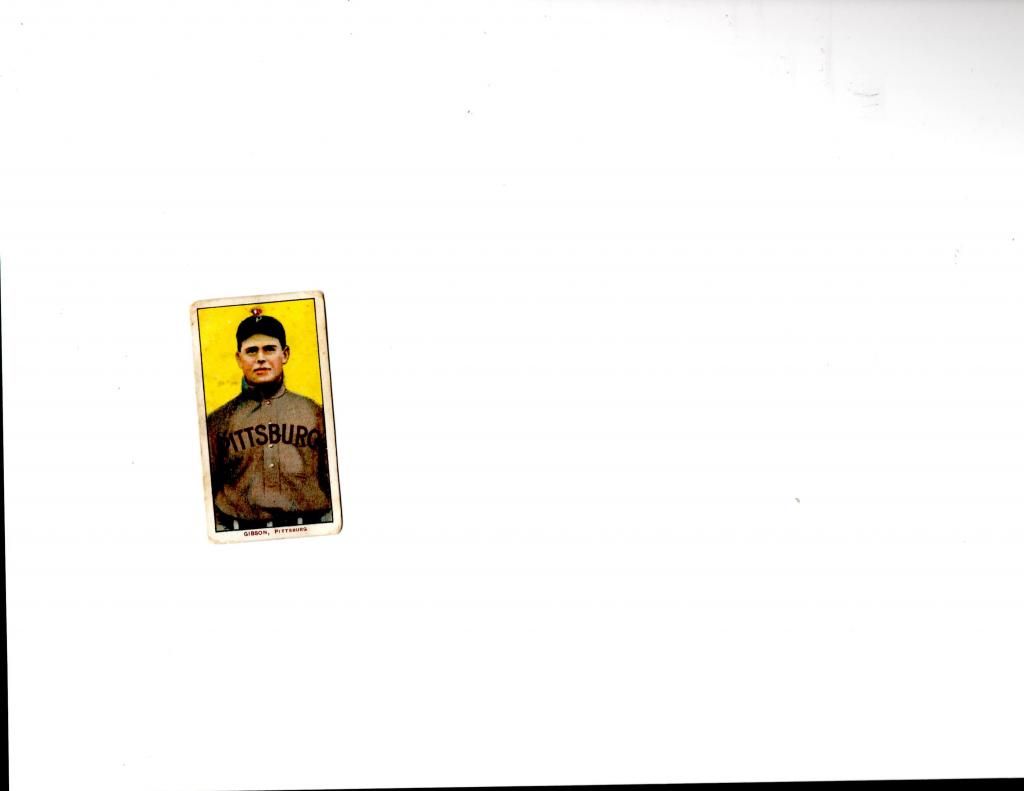

George Gibson

George C. Gibson (July 22, 1880 – January 25, 1967), nicknamed Mooney, was a Canadian baseball player (catcher) who caught for two different Major League teams, starting in 1905 with the Pittsburgh Pirates and ending his playing career with the New York Giants in 1918. In the 1920s and 1930s he served as manager for Pittsburgh and for the Chicago Cubs. Before that, however, Gibson started his managerial career with the Toronto Maple Leafs, a AAA Class team in the International League.

Gibson was the nephew of William Southam, founder of Southam Newspapers, the brother of Richard Southam, manager of the London Tecumsehs, and the father-in-law of Bill Warwick, a major league baseball player in the 1920s

The highlight of Gibson's playing career was winning the best-of-seven- games World Series with Pittsburgh in 1909 by beating Ty Cobb's Detroit Tigers four games to three.

Arriving back at the train station in his hometown of London, Ontario, on October 27, 1909, after winning the World Series, Gibson found more than 7,000 cheering fans to greet him. At the time, the population of London was approximately 35,000.

On September 9, 1909, Mooney caught his 112th consecutive game, breaking Chief Zimmer's 1890 record. Gibson's streak came to an end at 140 consecutive games behind the plate.

In 1921, Gibson, as manager of Pittsburgh, led the Pirates to his third consecutive first-division finish.

Born a stone's throw away from Tecumseh Park (today's Labatt Memorial Park) in London West, Gibson gained the nickname, "Mooney" early in his career due to his round, moon-like face. (One biographer disputes this, saying that Gibson picked up the nickname as a youngster when he played on a sandlot team known as the Mooneys.)[1]

At age 12, Gibson played for the Knox Baseball Club in a church league. In 1901, he played for the West London Stars of the Canadian League and the Struthers and McClary teams of the City League.

Today, there is a commemorative plaque prominently displayed at the entrance to the main grandstand at Labatt Park in Gibson's honour

Gibson first signed a pro contract in 1903 and developed his talents in Buffalo, New York of the Eastern League and in Montreal before joining the Pittsburgh Pirates two years later on July 2, 1905, at age 24. He had a strong throwing arm and led National League catchers in fielding percentage several times.

Gibson played in the Major Leagues until August 20, 1918, 12 years with the Pirates and two years with the New York Giants, appearing in 1,213 games.

Known as a developer of young pitchers, Gibson later managed the Pirates (1920–1922, 1932–1934) and the Chicago Cubs (1925).

On May 9, 1921, under manager George Gibson, the Pittsburgh Pirates beat the London Tecumsehs 8–7 at Tecumseh Park before 3,500 people in an exhibition baseball game. Before the game, Gibson and his team is presented with a silver loving cup by the London Kiwanis Club. Gibson thrills the locals by catching the opening inning with his 1909 battery mate Babe Adams and singling and scoring a run in his lone at-bat. London Mayor Sid Little entertains the team that evening at his home.

Gibson was named Canada's baseball player of the half century in 1958 and was the first baseball player elected to the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame. He was subsequently inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum in 1987 and was one of the inaugural 10 inductees into the London Sports Hall of Fame in 2001. In February 1955 while organizers were planning the charter season of the Eager Beaver Baseball Association, Gibson was named "honorary lifetime president

When Gibson lived at 252 Central Avenue in London during the 1920s and 1930s, his immediate neighbours to the east were members of the Labatt brewing family, with whom Gibson frequently socialized. It is believed that Gibson played a significant role in the decision by John and Hugh Labatt to purchase Tecumseh Park and donate it to the City (along with $10,000 for repairs and maintenance), which occurred on December 31, 1936, after which Tecumseh Park was officially renamed "The John Labatt Memorial Athletic Park."

Gibson died at age 86 in London and is buried at Campbell Cemetery in Komoka, Ontario, not far from his Delaware farm. Near Gibson's former farm is a road named in his honour after Gibson donated some land for public use to the area conservation authority of the day.

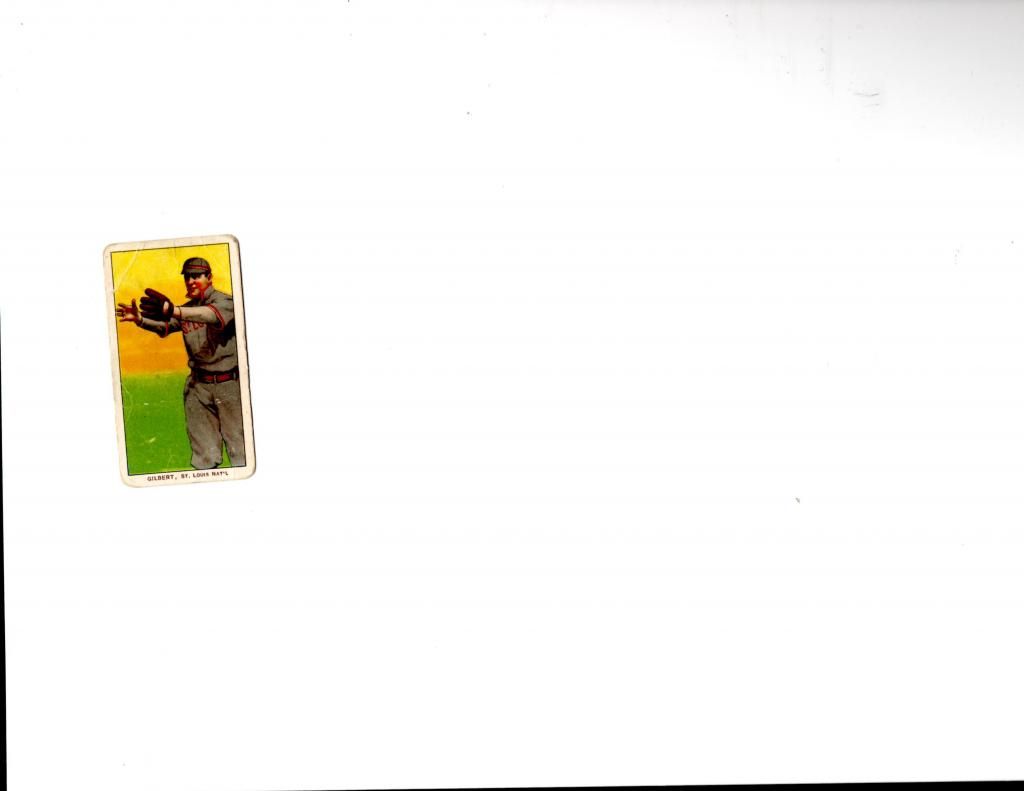

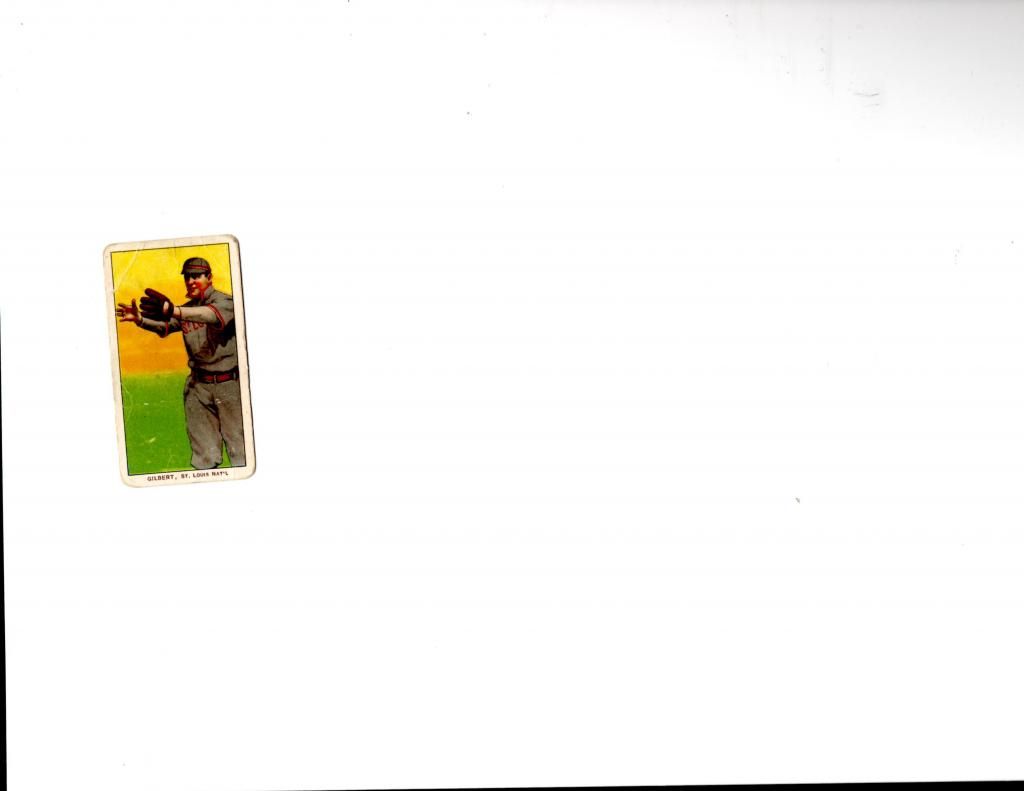

Billy Gilbert

William Oliver Gilbert (June 21, 1876 – August 8, 1927) was an American professional baseball second baseman who played from the 1890s through 1912. Gilbert played in Major League Baseball from 1901 to 1909, for the Milwaukee Brewers, Baltimore Orioles, New York Giants, and St. Louis Cardinals.

Standing at just 5 feet 4 inches (1.63 m), Gilbert was a weak hitter but a good defensive second baseman. He did hit .313 in the 1905 World Series, which the Giants won

Gilbert made his professional baseball debut in minor league baseball with Lewiston of the Maine State League and the Pawtucket Phenoms and Fall River Indians of the Class-B New England League in 1897.[1] He pitched for the Lyons franchise and the Johnston/Palmyra Mormans in the New York State League in 1898.[1] Now rated a Class-C league, Gilbert returned to the New York State League to play for the Utica Pent-Ups in 1899.[1]

The Milwaukee Brewers of the American League (AL) drafted Gilbert in 1900. They assigned him to the Syracuse Stars of the Class-A Eastern League for the season.[1]

Gilbert made his MLB debut with the Brewers in 1901. After the season, Baltimore Orioles player-manager John McGraw bought his contract from the Brewers prior to the 1902 season.[1]

McGraw jumped to the New York Giants of the National League during the 1902 season. He signed Gilbert to the Giants for the 1903 season and installed him as the team's starting second baseman.[1] Not a highly regarded hitter, Gilbert contributed with his bat as the Giants defeated the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1905 World Series,[2][3] leading the team in batting average during the series.[4]

He played with the Giants through the 1906 season. Down the stretch in 1906, McGraw replaced Gilbert with Sammy Strang, who produced better offense.[4] After the season, the Giants tried to assign Gilbert to the Newark Indians of the Class-A Eastern League.[5] Not wanting to play in Newark,[4] Gilbert refused to report. Wanting to stay in the NL, Gilbert attempted to negotiate a contract with the Brooklyn Superbas.[6]

Unable to sign with Brooklyn, he contemplated signing with an outlaw team.[7] Instead, Gilbert played for the Trenton Tigers of the Class-B Tri-State League in 1907, and coached the Columbia Lions, the college baseball team of Columbia University.[6]

Gilbert returned to MLB in 1908 with the St. Louis Cardinals. After the Cardinals fired John McCloskey as their manager after the 1908 season, Gilbert was considered for the job.[8][9] They instead acquired Roger Bresnahan and made him their player-manager.[10] He made his final MLB appearance on June 27, 1909, and served as a Cardinals' scout during the remainder of the season.[11] He was released by Cardinals manager Roger Bresnahan, a former teammate with the Giants, in March 1910.[12]

Gilbert played for the Albany Senators of the now Class-B New York State League in 1910.[13] He served as player-manager for the Erie Sailors when they competed in the Class-C Ohio-Pennsylvania League in 1911[13][14] and the Class-B Central League in 1912.[15] Gilbert stayed with Erie, competing in the Class-B Interstate League, as manager in 1913.[16] He was fired after the season.[17]

Gilbert spent the next few seasons managing independent teams in New York. Gilbert was hired to manage the Waterbury Brasscos in the Class-A Eastern League in 1921[18] and 1922, leading them to a second-place finish.[19] He managed the Denver Bears of the Class-A Western League in 1923,[20][21] and Pittsfield Hillies in the Eastern League in 1924.[19] Gilbert then served as a scout for the Newark Indians of the Class-AA International League.[22]

During his career, Gilbert was highly regarded for his work ethic.[23] He was described as taking after McGraw

Gilbert died on August 8, 1927 at his home in New York as a result of apoplexy.[25] He attended a doubleheader in Newark the day before, and was reportedly in good health.[22]

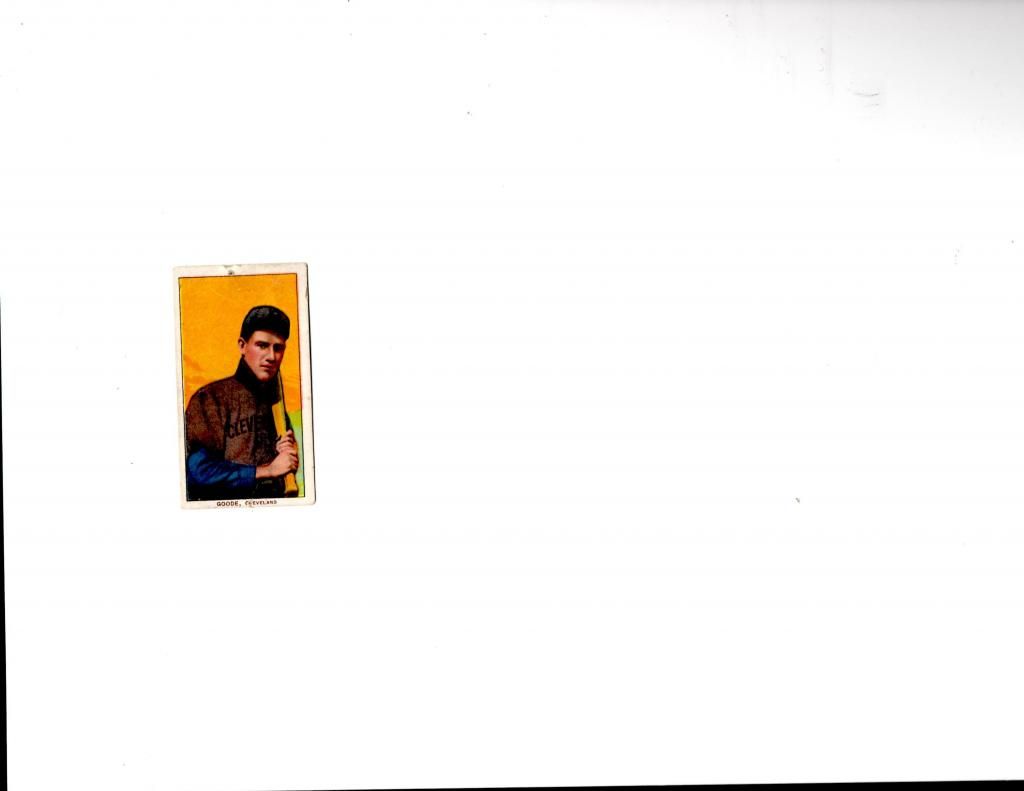

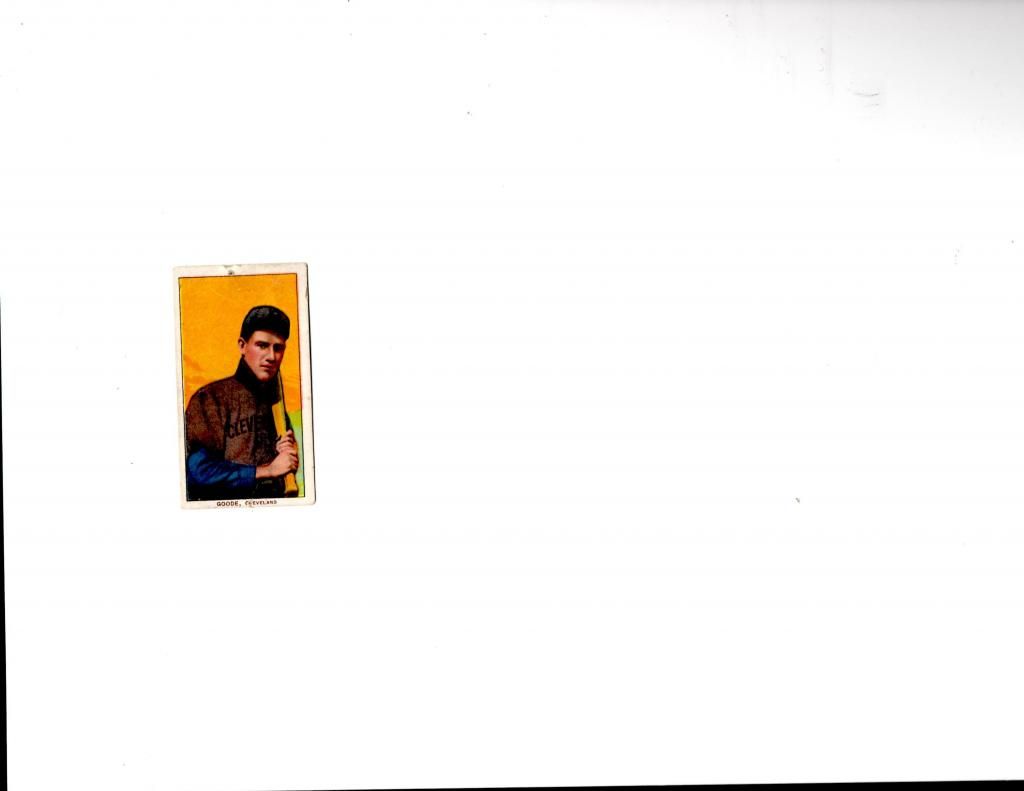

Wilbur Goode

Wilbur David "Lefty" Good (September 28, 1885 – December 30, 1963) born in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, was an outfielder for the New York Highlanders (1905), Cleveland Naps (1908–09), Boston Doves/Rustlers (1910–11), Chicago Cubs (1911–15), Philadelphia Phillies (1916) and Chicago White Sox (1918).

In 11 seasons he played in 749 games and had 2,364 at-bats, 324 runs, 609 hits, 84 doubles, 44 triples, 9 home runs, 187 RBI, 104 stolen bases, 190 walks, a .258 batting average, a .322 on-base percentage, a .342 slugging percentage, 808 total bases and 60 sacrifice hits.

He died in Brooksville, Florida at the age of 78.

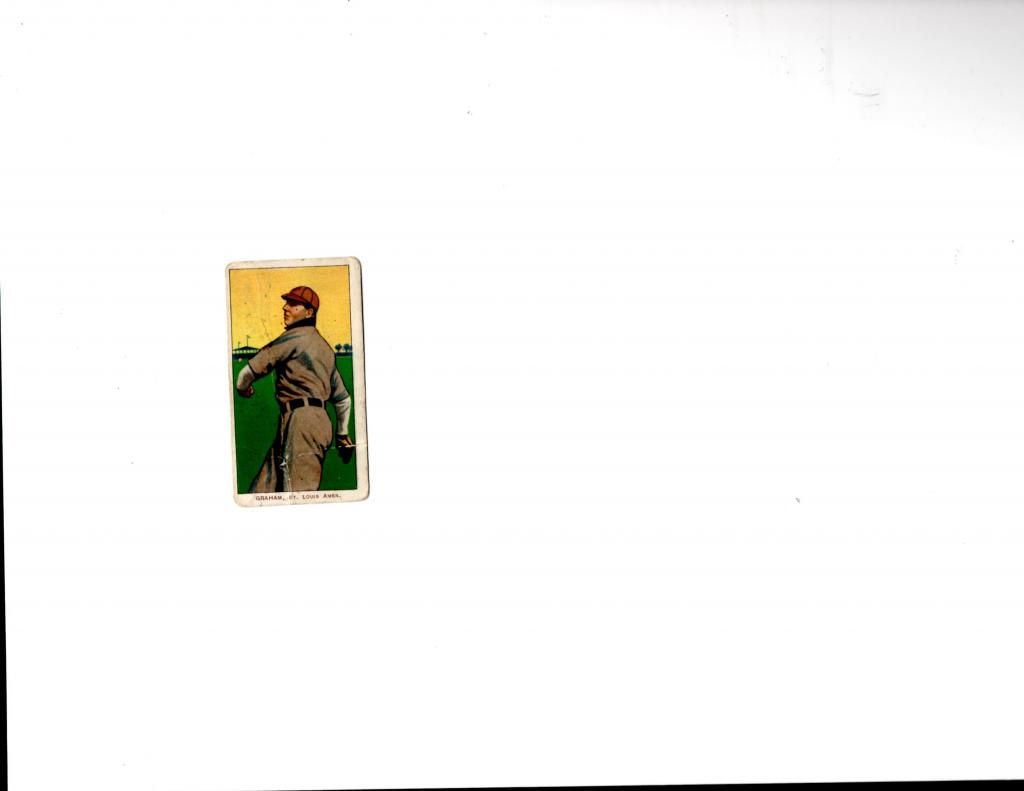

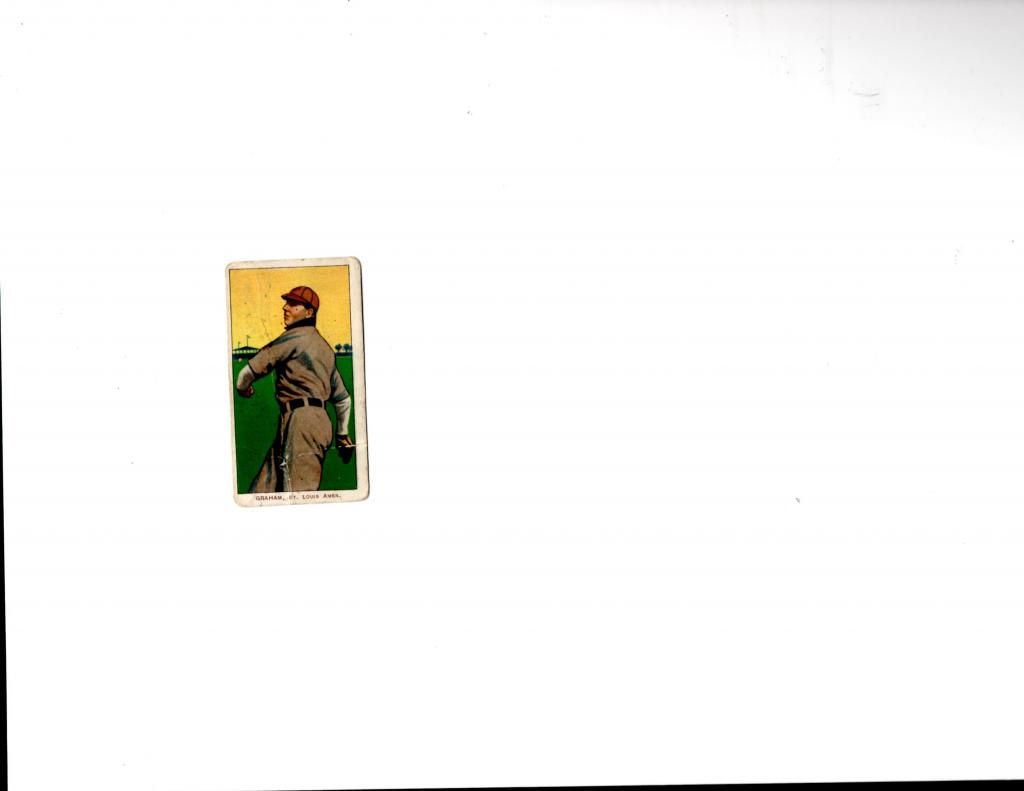

Bill Graham

William James Grahame (July 22, 1884 in Owosso, Michigan – February 15, 1936 in Holt, Michigan), was a professional baseball player who played pitcher in the Major Leagues in 1908-1910. He would play for the St. Louis Browns

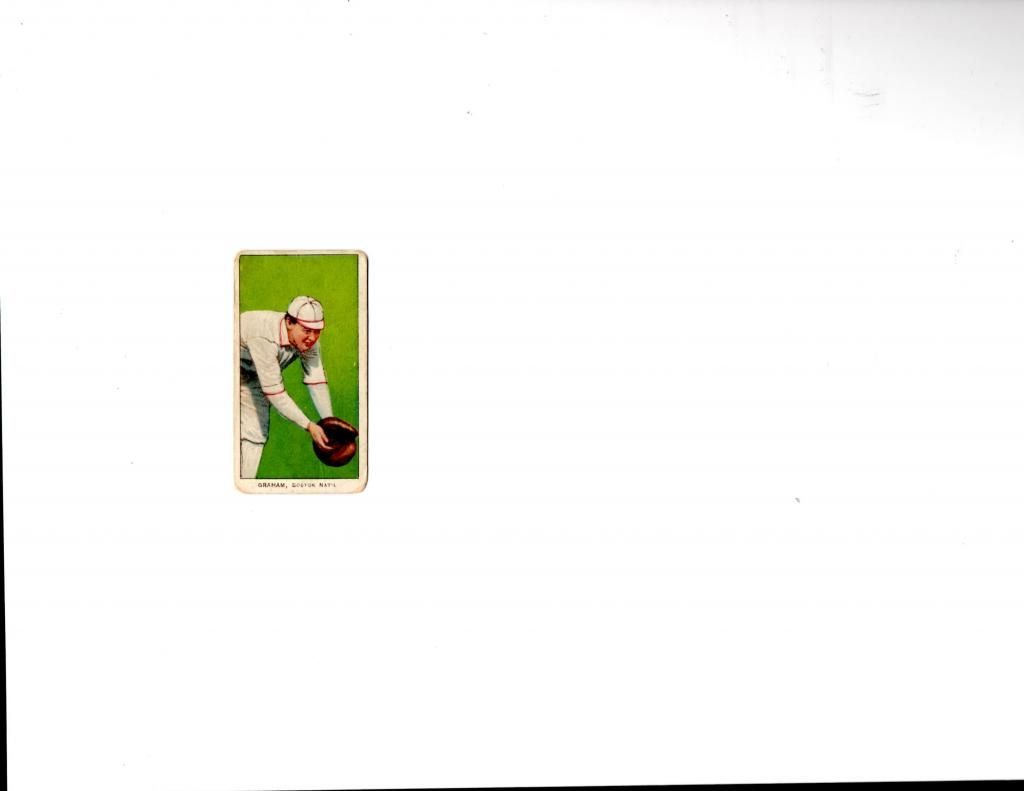

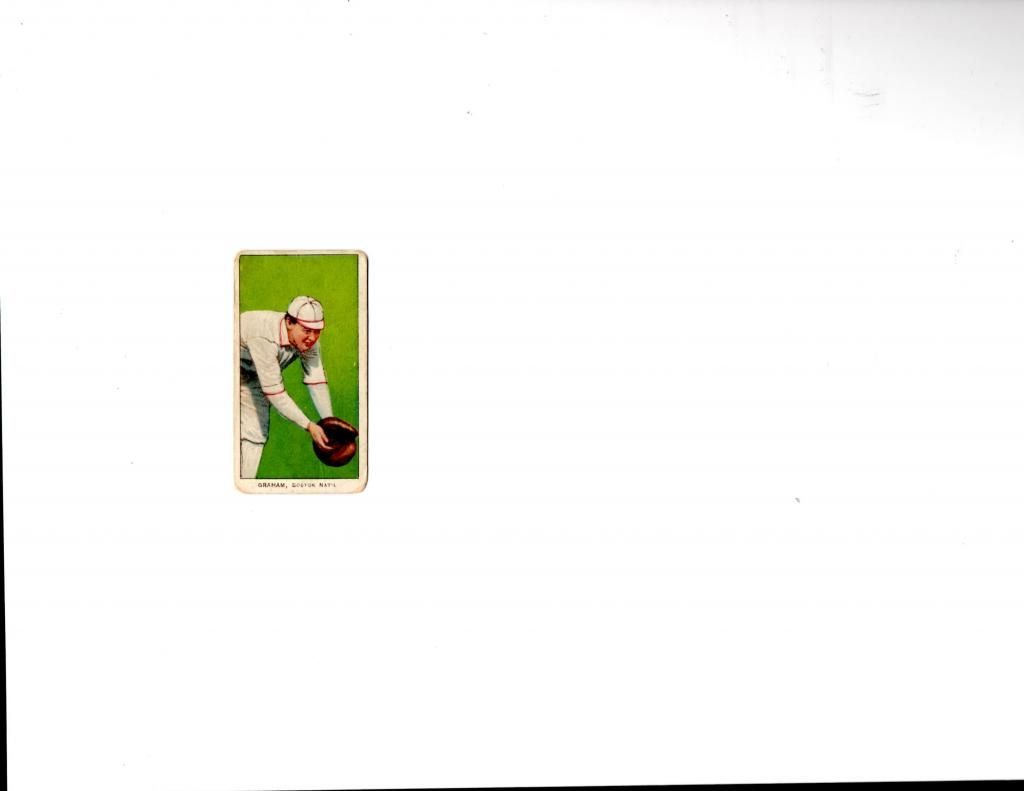

Peaches Graham

George Frederick "Peaches" Graham (March 23, 1877 – July 25, 1939) was a baseball catcher for the Cleveland Bronchos, Chicago Cubs, Boston Doves/Rustlers, and Philadelphia Phillies.

Born in Aledo, Illinois, Graham played seven seasons of Major League Baseball over the span of eleven years. He debuted in 1902 with the Bronchos as a second baseman, and came back in 1903 with the Cubs as a pitcher, but only pitched in one game, a loss.[2] After a five-year hiatus, Graham returned in 1908 as a utility player with the Braves. He started games as a catcher, second baseman, outfielder, third baseman, and shortstop, but was predominantly a catcher. Graham was traded mid-season 1911 to the Cubs, but only played there for three months before being traded for Dick Cotter to Philadelphia, where he would finish his major league career after the 1912 season at the age of thirty-five.[3]

He had a son, Jack, born in 1916, who would go on to play professional baseball. Graham died in Long Beach, California at the age of sixty-two.[3]

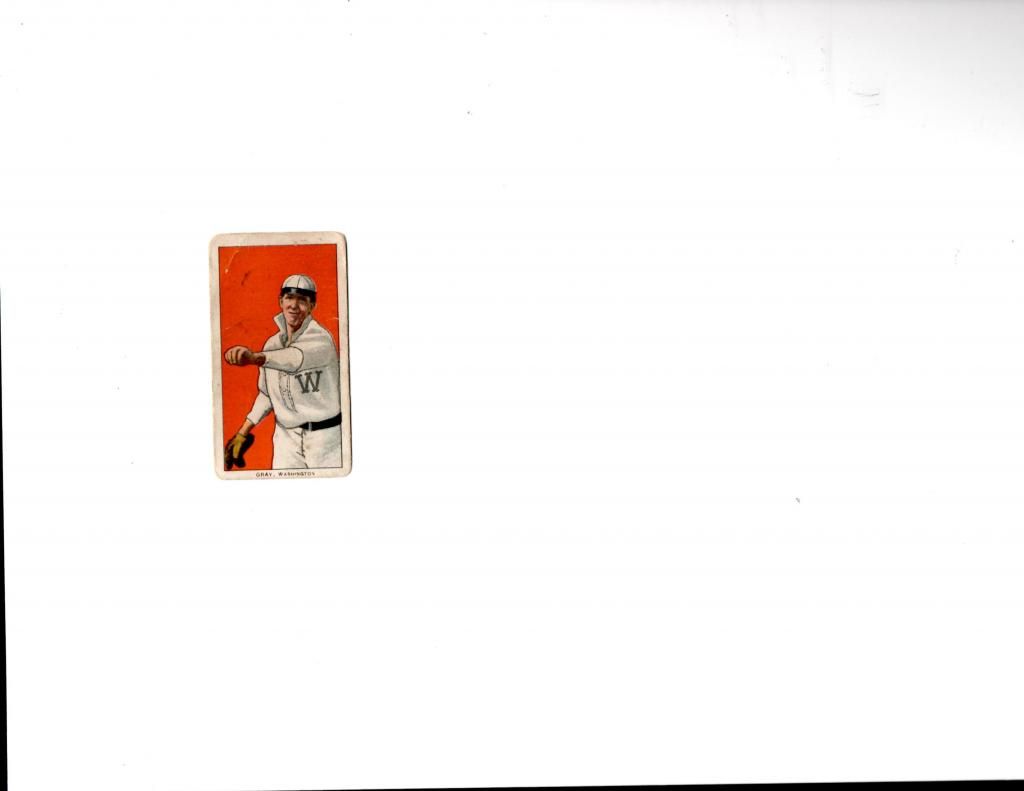

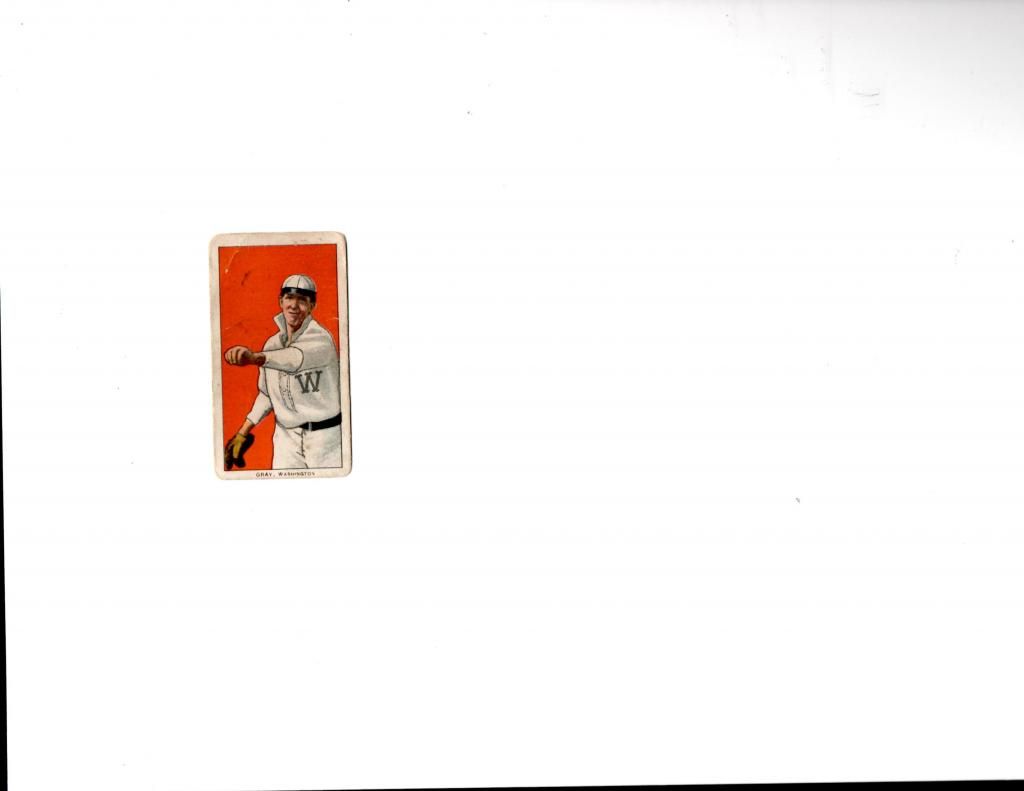

Dolly Gray

William Denton "Dolly" Gray (December 4, 1878 in Houghton, Michigan – April 4, 1956 in Yuba City, California) was a left-handed professional baseball pitcher who played from 1909 to 1911 for the Washington Senators. One source says he was born in Ishpeming, Michigan.[1]

Dolly Gray began his professional career during or before the 1902 season. In 1902, he pitched for the Los Angeles Angels of the old California League. Following the 1902 season, the Angels joined to the Pacific Coast League, and in 1903 they had one of the greatest seasons in minor league baseball history.[2] Gray went 23–20 with a 3.55 ERA that season. In 1904, Gray went 24–26, in 1905, he went 30–16, in 1906, he went 7–2 (during the 1906 season, Gray and many other West Coast players left to play on the East Coast after the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake,[2] in 1907 he went 32–14 and in 1908 he went 26–11. He played in one game in 1909, winning it. In 1905 and 1907, he led the league in winning percentage.

Major league baseball[edit]

A 30-year-old rookie, Gray made his major league debut on April 13, 1909. He made 36 appearances in his rookie season, starting 26 of those games. He we 5–19 with 19 complete games. That year, he led the league in earned runs allowed (87), was third in losses, seventh in walks allowed (77) and eighth in appearances. Gray gave up Tris Speaker's first big league home run on May 3 of that year,[3] and on August 28 of that year, he set the major league record for most walks allowed in an inning, when he walked eight batters in the second inning. He also set the record for most consecutive walks in an inning, when he walked seven batters in a row. In total, Gray allowed 11 walks that game, giving up six runs and earning the loss in the process. Had he had better control, he may very well have won the game – he threw a one-hitter.[4]

In 1910, Gray went 8–19 with a 2.63 ERA. He was second in the league in losses that year, fifth in wild pitches (9), ninth in earned runs allowed (67) and ninth in hit batsmen (10).

On April 12, 1911, Gray threw the very first pitch in Griffith Stadium history. He also won the game that day, beating opposing pitcher Smoky Joe Wood. That would be one of only two wins for Gray in 1912 – overall that season, he went 2–13 with a 5.06 ERA. His ten wild pitches that season were fourth most in the league, and his ten games finished were eighth most in the league. Gray played in his final major league game on September 29, 1911.

Gray went 15–51 with a 3.52 ERA in his three-year career. His .227 winning percentage is one of the worst all-time among pitchers with at least 50 career decisions. As a batter, Gray was pretty solid for a pitcher – he hit .202 in 218 big league at bats.

Statistically, Gray is most similar to Blondie Purcell, according to the Similarity Scores at Baseball-Reference.com.

Post-big league career[edit]

Following his major league career, Gray pitched in the Pacific Coast league from 1912 to 1913, retiring after the 1913 season.[2] He played for the Vernon Tigers and Oakland Oaks in that time.[5]

Following his death, he was buried in Sutter Cemetery in Sutter, California.[6]

In 2008, Gray was inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, along with Wheezer Dell, Casey Stengel and Lee Susman.[5]

The nickname[edit]

Gray got his nickname Dolly from the 19th century song Nellie Gray, composed by Benjamin Hanby. One line in the song goes darling Nellie Gray, they have taken you away. His teammates mangled and distorted it darling and it became "Dolly."[2]

Another source says his nickname came from the song Goodbye, Dolly Gray.

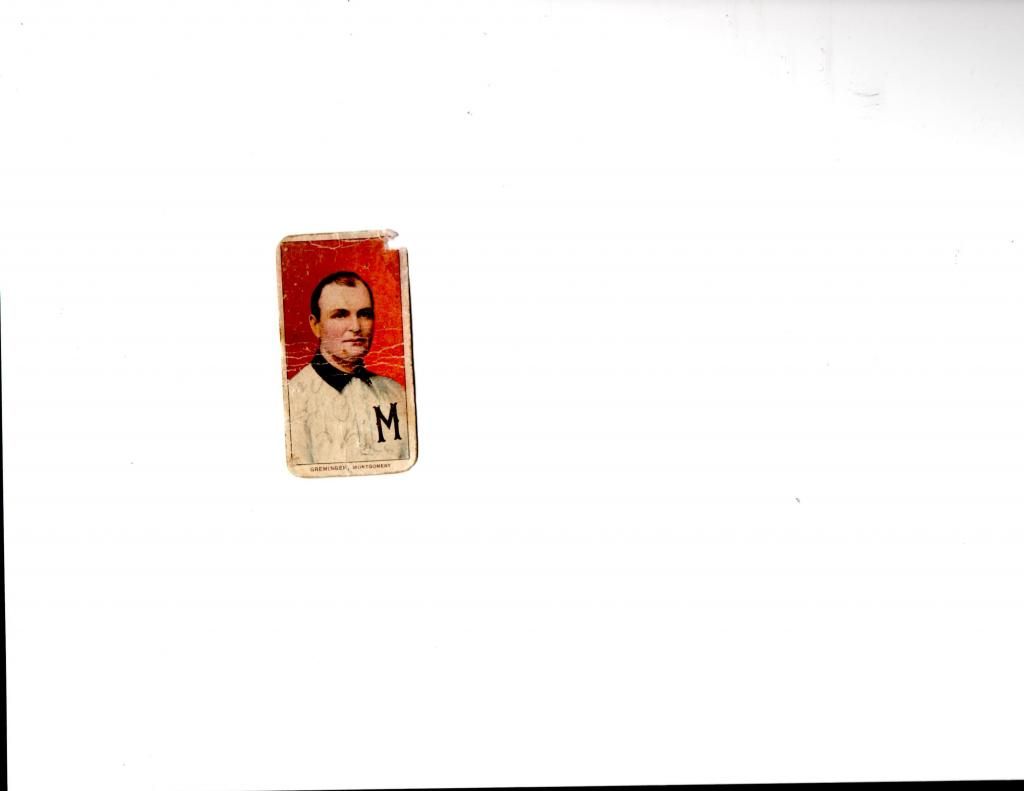

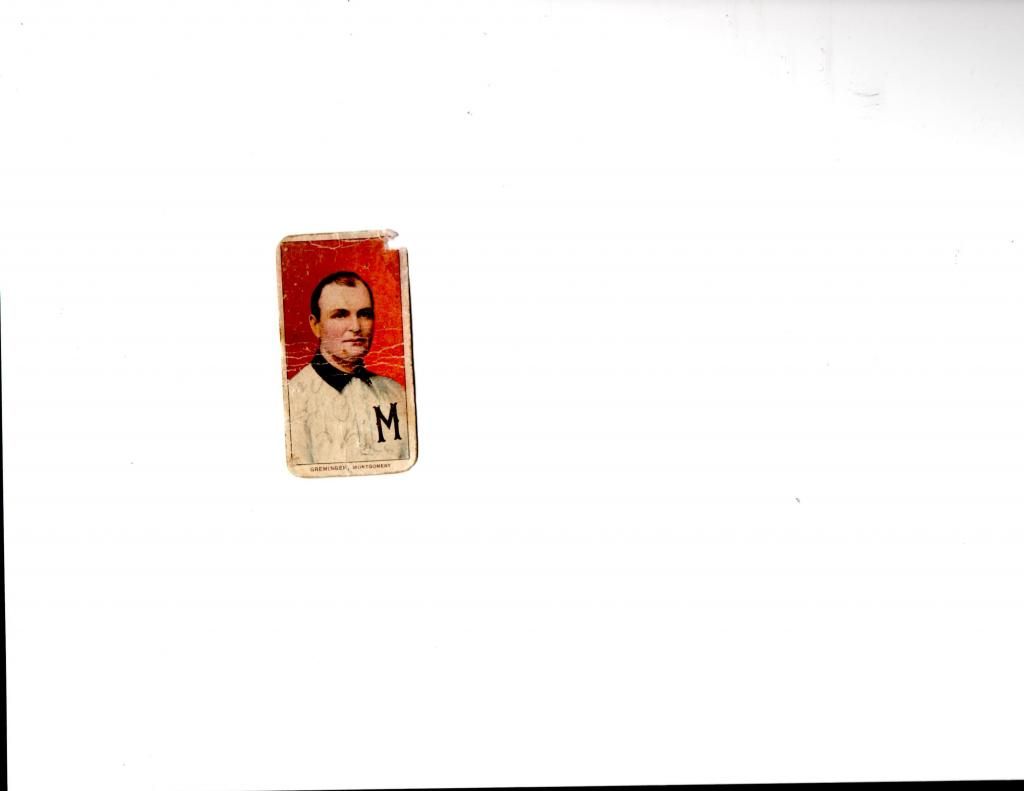

Ed Grimminger

Lorenzo Edward Gremminger (March 30, 1874 – May 26, 1942), nicknamed "Battleship," was a professional baseball player from 1895 to 1912. He played four seasons of Major League Baseball as a third baseman for the Cleveland Spiders (1895), Boston Beaneaters (1902–03), and Detroit Tigers (1904).

In 383 major league games, Gremminger compiled a .251 batting average, .301 on-base percentage, and .340 slugging percentage, with 164 RBIs and 89 extra base hits. He was among the National League leaders in 1902 with 20 doubles (9th), 12 triples (5th), 65 RBIs (8th), and 33 extra base hits (9th). He was also ranked ninth in the National League in 1903 with five home runs.[1]

Gremminger also played fifteen seasons of minor league baseball, including stints with the Buffalo Bisons (1896-1899), Rochester Bronchos (1900), Minneapolis Millers (1904-1907), Montgomery Senators (1908-1910), and Canton Deubers/Statesman (1911-1912).[2]

Gremminger was born and died in Canton, Ohio.

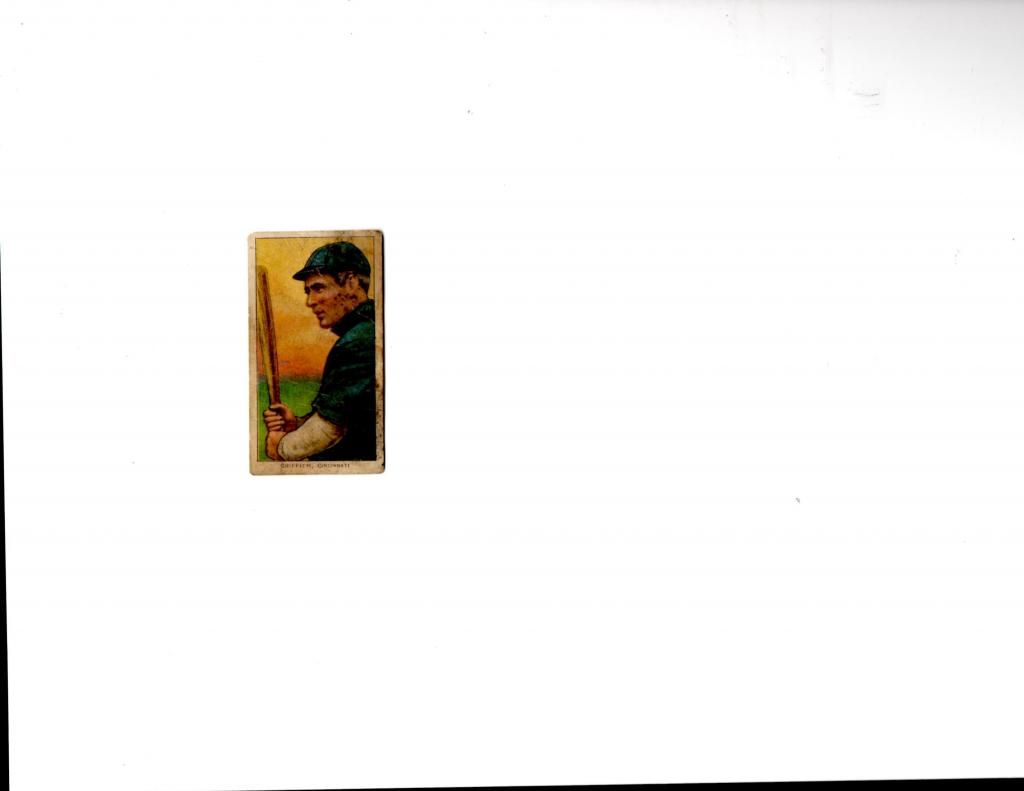

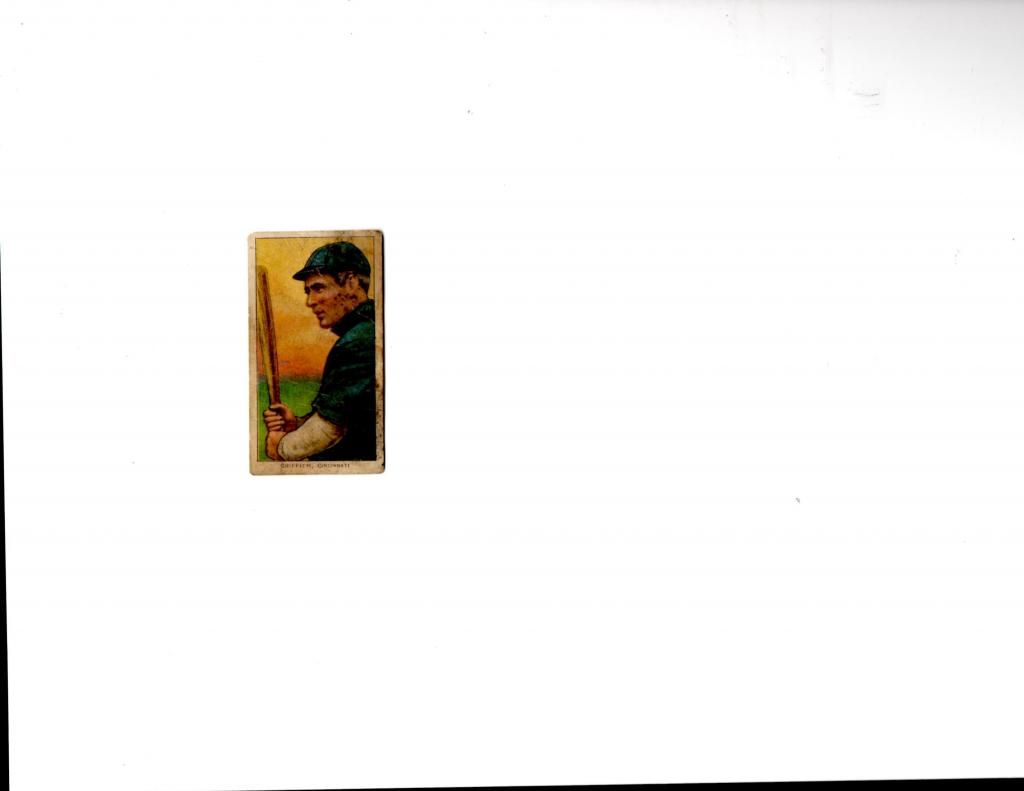

Clark Griffith ( Started the tradition of Presidents throwing the first pitch)

Clark Calvin Griffith (November 20, 1869 – October 27, 1955[1]), nicknamed "The Old Fox", was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher, manager and team owner. He began his MLB playing career with the St. Louis Browns (1891), Boston Reds (1891), and Chicago Colts/Orphans (1893–1900). He then served as player-manager for the Chicago White Stockings (1901–1902) and New York Highlanders (1903–1907).

He retired as a player after the 1907 season, remaining manager of the Highlanders in 1908. He managed the Cincinnati Reds (1909–1911) and Washington Senators (1912–1920), making some appearances as a player with both teams. He owned the Senators from 1920 until his death in 1955. Sometimes known for being a thrifty executive, Griffith is also remembered for attracting talented players from the National League to play for the Senators when the American League was in its infancy. Griffith was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946.

Griffith was born in Clear Creek, Missouri, to Isaiah and Sarah Anne Griffith. His parents were of Welsh ancestry. They had lived in Illinois prior to Clark Griffith's birth. The family took a covered wagon west toward the Oklahoma Territory. Along the way, the family encountered hungry and disenchanted people returning from the Oklahoma Territory, so they decided to settle in Missouri. Griffith grew up with five siblings, four of them older.[2]

When Griffith was a small child, his father was killed in a hunting accident when fellow hunters mistook him for a deer.[3] Sarah Griffith struggled to raise her children as a widow, but Clark Griffith later said that his neighbors in Missouri had been very helpful to his mother, planting crops for her and the children. Fearing a malaria epidemic that was sweeping through the area, the Griffith family moved to Bloomington, Illinois.[4]

A childhood incident taught him about the money side to baseball, Griffith recalled. When he was 13, he and a few other young boys had raised $1.25 to buy a baseball. They sent one of the boys 12 miles on horseback to make the purchase. The ball burst on the second time that it was struck. Griffith later found out that the boy who purchased the ball only spent a quarter, keeping the leftover dollar.[5] At the age of seventeen, Griffith had made ten dollars pitching in a local baseball game in Hoopeston, Illinois

In 1939, sportswriter Bob Considine expressed disappointment that Griffith had not already been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He referred to Griffith as "the real father of the American League", citing the fact that Griffith had been a key force in attracting National League players to join the American League teams in their initial years. He wrote that Griffith "belongs in any hall of fame where the elective body is composed of sports writers, for no other reason than that no sports writer ever came away from the old guy without a story. Some of them were even kindly stories."[12]

Griffith had appeared on ballot for the second Baseball Hall of Fame election (1937), but he received two percent of the possible votes.[13] In 1938, he received votes on only 3.8 percent of the submitted ballots.[14] He received votes on 7.3 percent of ballots the next year.[15] The Hall of Fame held only triennial elecctions for a few years.[16] In 1942, 30.5 percent of voters submitted Griffith's name.[17]

Griffith was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Old Timers Committee in 1946. He was honored at the induction ceremony the following year. Author Dennis Corcoran writes that Griffith had attended the initial Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1939 but that there is no evidence that Griffith came to the 1947 induction or any other ceremony

In October 1955, Griffith was in the hospital with neuritis when he suffered a stomach hemorrhage.[19] Though he appeared to be improving, Griffith died a few days after he was hospitalized. He was nearing his 86th birthday.[20]

After his death, newspaper accounts described Griffith's longtime relationships with U.S. presidents. During World War I, he successfully petitioned Woodrow Wilson to allow the continuation of baseball. He did the same with Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. He had also begun a tradition of presidents throwing out the ceremonial first pitch at a season's first Opening Day game, which started with William Howard Taft.[20] When the Baseball Hall of Fame was being built and was looking for baseball memorabilia, Griffith donated several photographs of these presidential first pitches.[18]

League president Will Harridge called Griffith "one of the game's all-time great figures."[21] Griffith was survived by his wife, who died of a heart attack two years later.[22] He and his wife had no children, but they raised several relatives.[23] A nephew who became his adopted son, Calvin Griffith, took over the team after his death and led efforts to have the club moved to Minnesota and become the Twins. Another nephew, Sherry Robertson, was a pitcher for the Senators and the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1940s and 1950s.[24]

A monument was erected in honor of Griffith at Griffith Stadium. After the stadium was demolished in 1964, the obelisk was moved to Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium, where the Washington Nationals played between 2005 and 2007.[25] A collegiate baseball league, the National Capital City Junior League, was renamed in honor of Griffith after his death.[26] The league suspended operations in 2010.

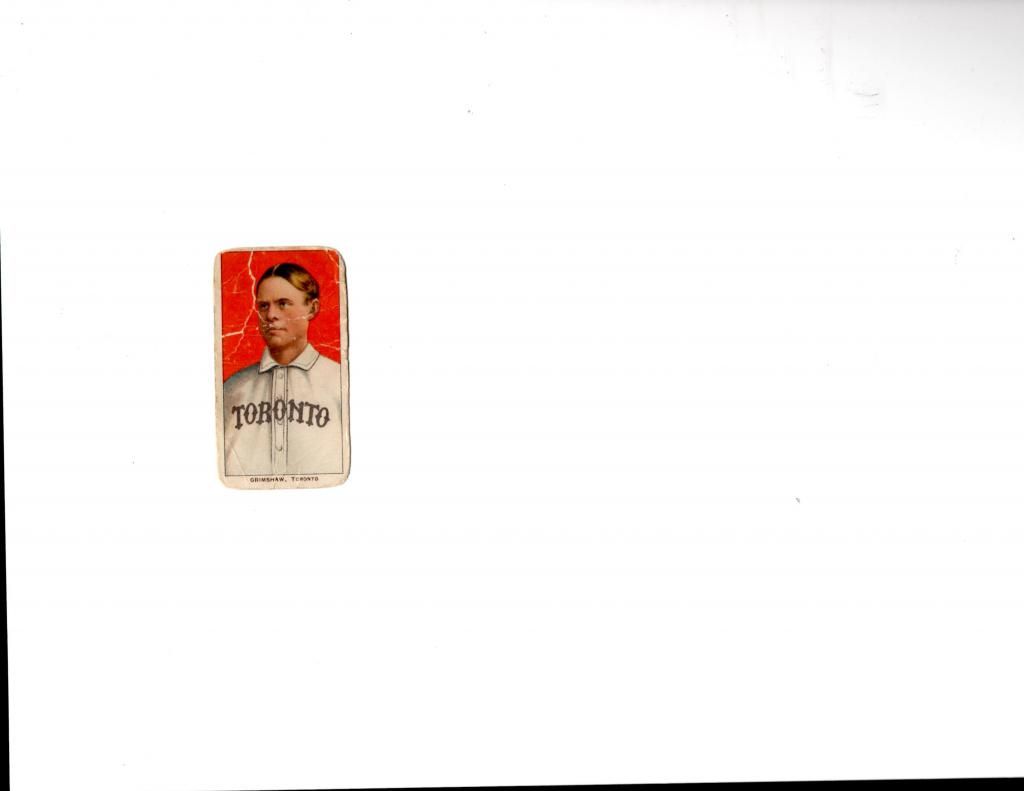

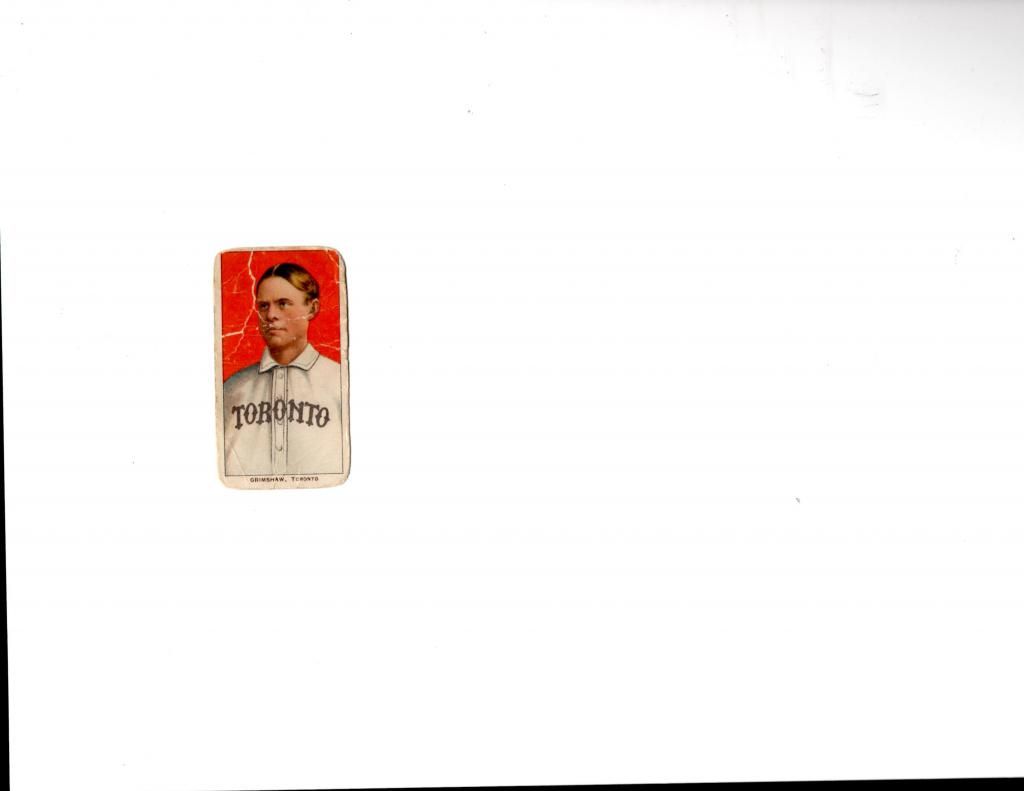

Moose Grimshaw

Myron Frederick "Moose" Grimshaw (November 30, 1875 – December 11, 1936) was a right fielder in Major League Baseball who played from 1905 through 1907 for the Boston Americans. Listed at 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m), 173 lb., Grimshaw was a switch-hitter and threw right-handed. He was born in St. Johnsville, New York, but raised in Canajoharie, New York.

In a three-season career, Grimshaw was a .256 hitter (229-for-894) with four home runs and 116 RBI in 259 games, including 104 runs, 31 doubles, 16 triples, and 15 stolen bases.

Grimshaw died in Canajoharie, New York at age 61

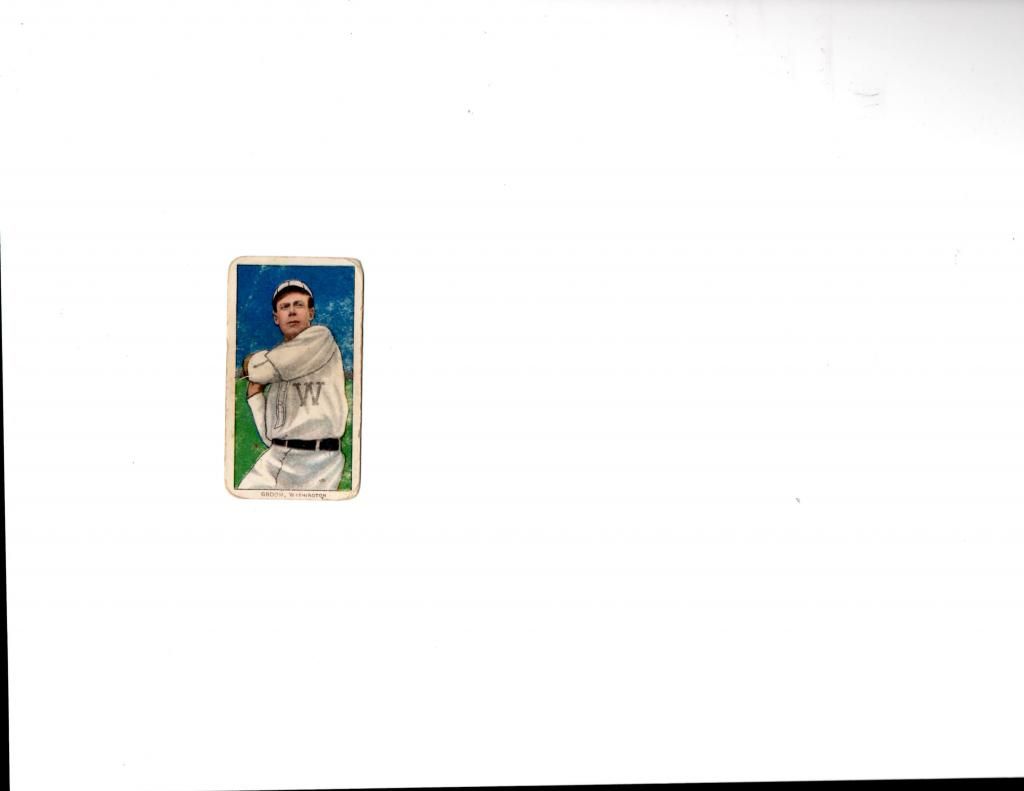

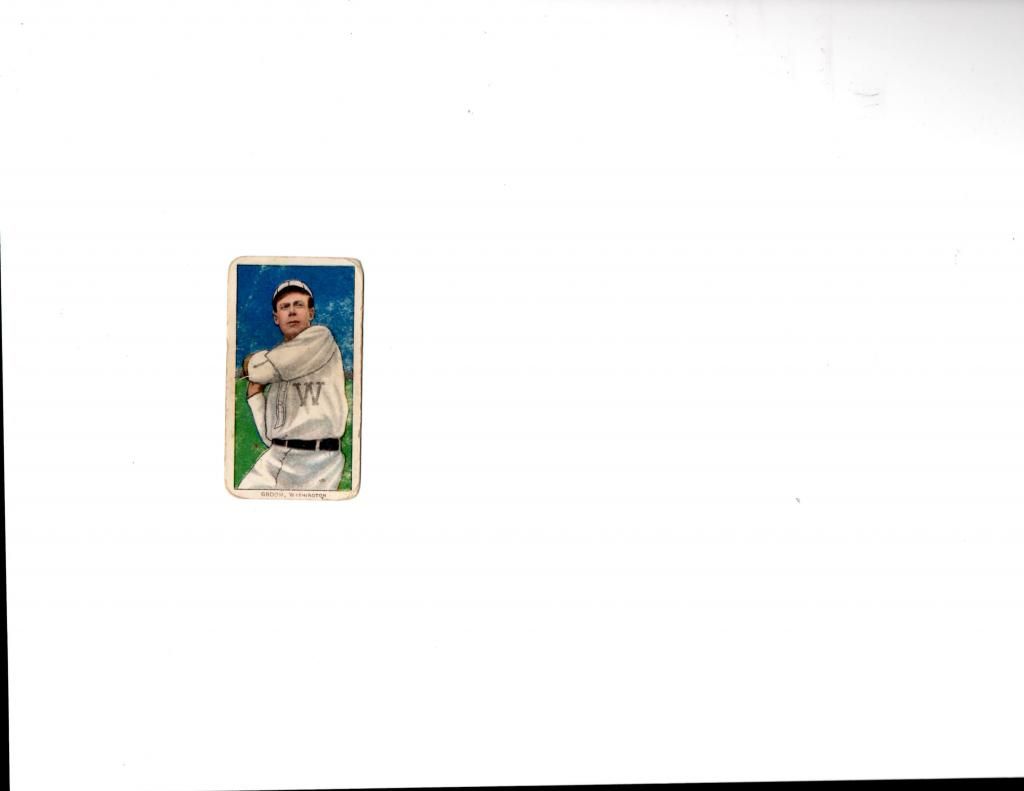

Bob Groom

Robert Groom (September 12, 1884 – February 19, 1948), was a professional baseball player who played as a pitcher in two midwest minor leagues and the Pacific Coast League from 1904 to 1908, and then in the Major Leagues from 1909 to 1918. He pitched for the Washington Senators (1909–1913), St. Louis Terriers (Federal League, 1914–1915), St. Louis Browns (1916–1917), and Cleveland Indians (1918).

On May 6, 1917, while with the Browns, Groom no-hit the eventual World Champion Chicago White Sox 3–0. The no-hitter came in the second game of Sunday double-header, after Groom preserved the win in the first game, pitching the last two innings without allowing a hit. It also came the day after teammate Ernie Koob's 1–0 no-hitter against the White Sox; to date, Koob and Groom are the only teammates to pitch no-hitters on consecutive days. His best major league season was with the 1912 Senators, when he won 24 games and Washington finished second in the American League. During his debut season, Groom became the first pitcher to achieve 19 consecutive losses in a season, a record which was equalled in 1916 by Jack Nabors.[1]

After the 1918 season, Bob Groom returned to Belleville, where he managed his family's coal mining operation and, in the summers, pitched for and managed local teams into the 1920s, most notably Belleville's White Rose team. Throughout the 20s and 30s he was involved with the St. Louis Trolley League as a mentor, and in 1938, he was asked by the George E. Hilgard American Legion Post 58 to form Belleville's first tournament team. He did and coached them to the state and regional championships in their first season. He led the "Hilgards" through 1944, and for his role in founding the team was inducted into the Hilgard Hall of Fame in February 2008. A marker in his honor, part of a series that grew out of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) Deadball Stars books, was presented on June 5, 2008, at the Belleville Hilgards' home ballpark, Whitey Herzog Field.

![[Image: roughdraft_edited-1.jpg]](http://i51.photobucket.com/albums/f354/blayneroessler/roughdraft_edited-1.jpg)

Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-12-2015, 09:17 PM

(This post was last modified: 03-21-2015, 08:20 PM by waynetalger.)

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Groom

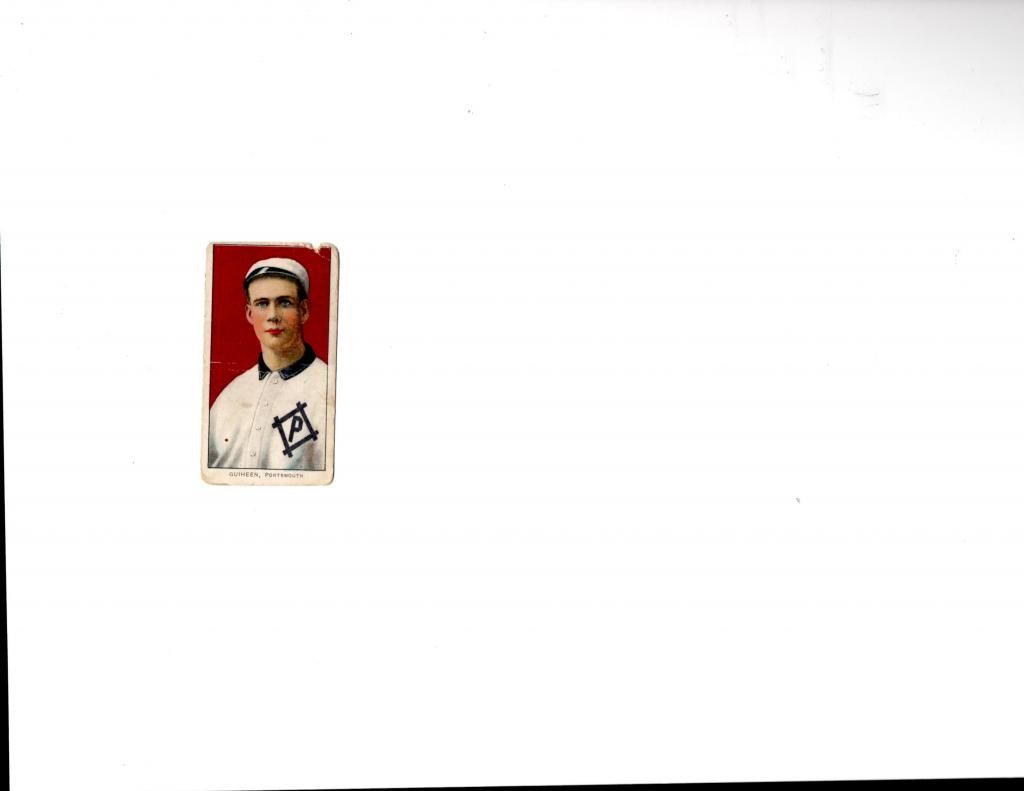

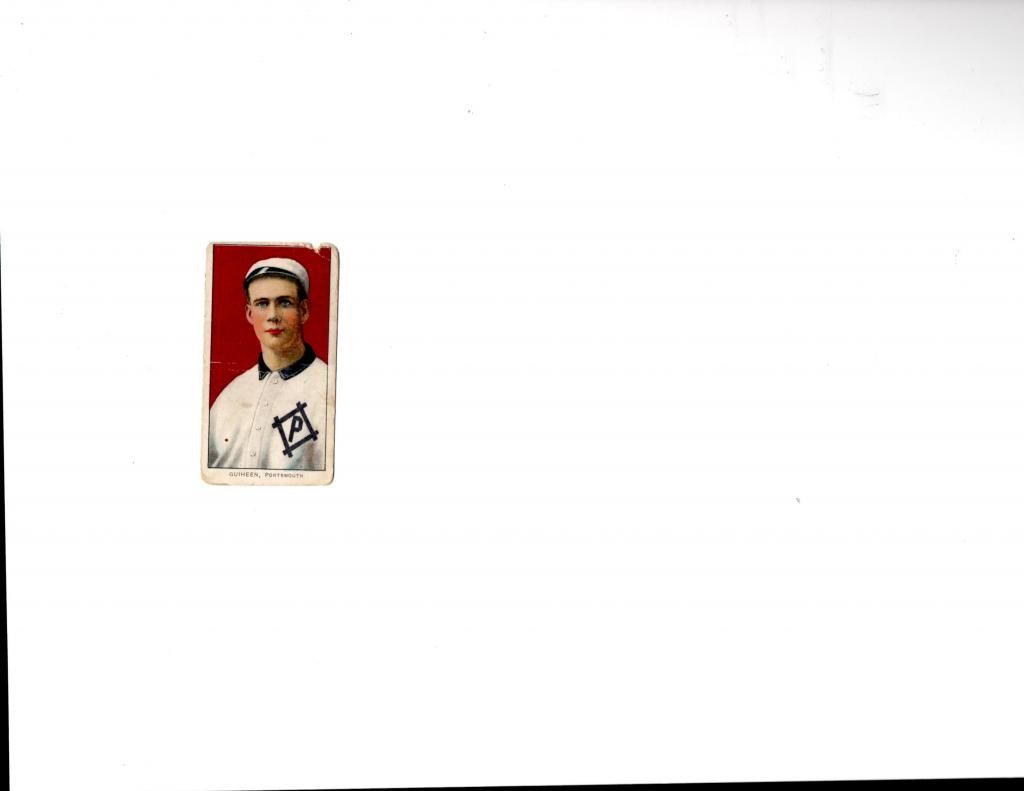

Tom Guiheen

Thomas Aloysius Guiheen

Positions: Second Baseman and Third Baseman

Born: December 27, 1882 in Vermont, US

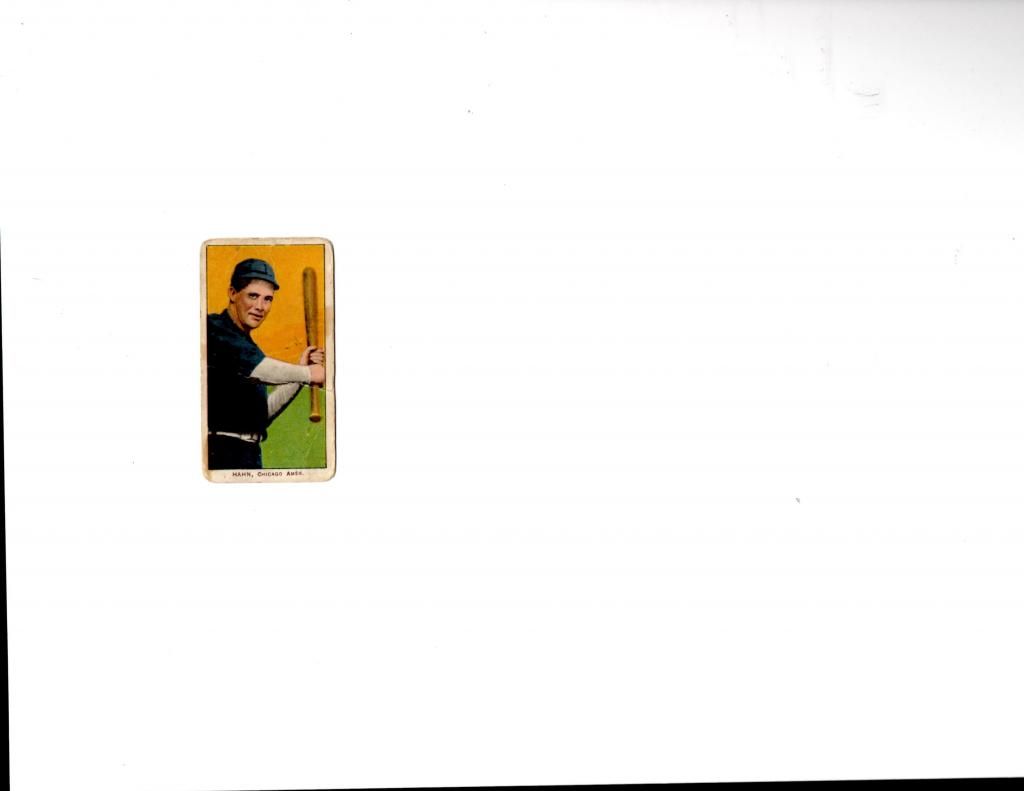

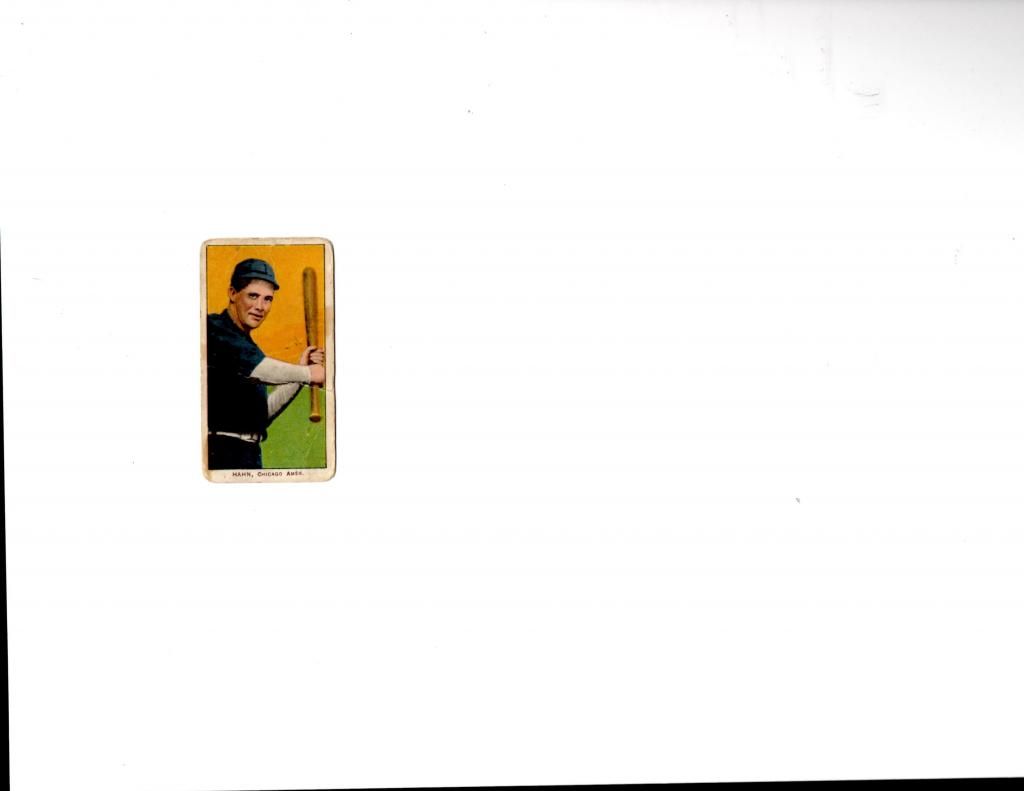

Ed Hahn (pottery maker, night watchman)

William Edgar Hahn (August 27, 1875 – November 29, 1941) was an outfielder in Major League Baseball from 1905 to 1910. He played for the Chicago White Sox and New York Highlanders

Hahn, who was born in Nevada, Ohio, started his professional baseball career at the age of 27 in the Cotton States League. In August 1905, he was batting .305 for the New Orleans Pelicans[1] and was purchased by the American League's Highlanders. He got off to a slow start in 1906 and was sold to the White Sox.[2] He became the team's starting right fielder. Hahn batted just .227 for the season but ranked third in the league in walks (72) and hits by pitches (11).[3] His style of play fit right in with the White Sox, who were known as "the Hitless Wonders."[4]

The White Sox won the pennant and faced the heavily favored Chicago Cubs in the 1906 World Series. Hahn, the team's leadoff hitter,[4] was the first batter of the series. He went 0 for 6 during the first two games. In game 3, he was hit in the face by a Jack Pfiester curveball and suffered a broken nose. He walked to the Cook County Hospital, which was a block away, for treatment.[5] The next day, he was back on the field for game 4, wearing a rubber air hose on his nostril. He received "loud and long" cheers from the crowd at his appearance.[6]

After getting hit, Hahn went 6 for 14 (.429) against the Cubs' pitching.[7] He scored two runs in game 5 and two more in game 6 as the White Sox pulled off one of the biggest upsets in World Series history.[8] It was the team's first Series win.[9]

1907 was Hahn's best season in the major leagues. He finished in the league's top five in runs (87) scored, walks (84), and hits by pitches (12), while batting .255. He also led all outfielders with a .990 fielding percentage.[3]

Hahn had another solid year in 1908. However, he hit poorly in 1909 and 1910 and then went down to the minors. In 1911, he was a player-manager for the Mansfield Brownies of the Ohio-Pennsylvania League. He then played five seasons for the Western League's Des Moines Boosters before retiring.[1]

Hahn had owned a pottery business during the offseasons.[2] After his baseball days were over, he became a night watchman for a cement company plant in Des Moines, Iowa.[10] He died in 1941.

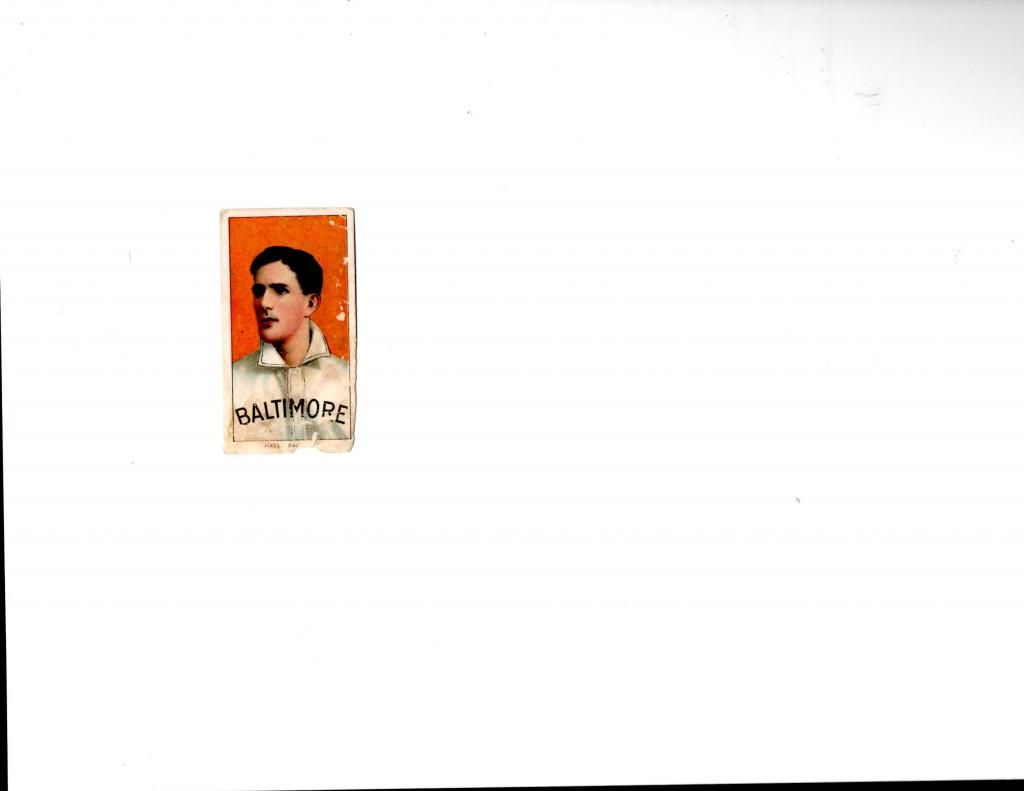

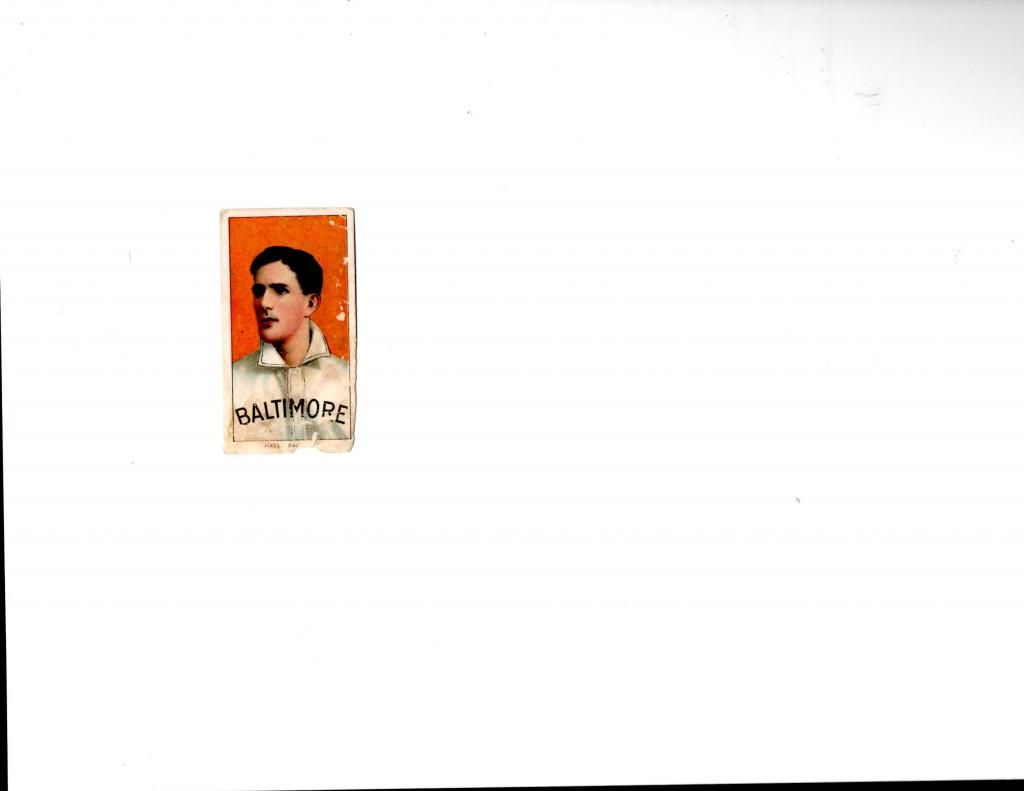

Bob Hall (wonder how he got in the T-206 set when his last game was 1905)

Robert Prill Hall (December 20, 1878, in Baltimore, Maryland – December 1, 1950, in Wellesley, Massachusetts), was a professional baseball player who played infield and outfield during the 1904 and 1905 seasons. He was a utility player including games at Right field, Center field, Left field, first base, second base, shortstop, and third base. Bob played for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1904, and the New York Giants and Brooklyn Superbas in 1905. Hall made his debut on April 18, 1904. In 103 career games, he had 75 hits in 369 at bats, which is a .203 average. He had 2 home runs, 32 RBIs, and 13 stolen bases. Hall played in his final game on October 7, 1905, and died on December 1, 1950, in Wellesley, Massachusetts

Bill Hallman

William Harry "Bill" Hallman (March 15, 1876 – April 23, 1950) was an American professional baseball player. As an outfielder, he played for three different team in Major League Baseball; the Milwaukee Brewers in 1901, the Chicago White Sox in 1903, and the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1906 and 1907.[1] Additionally, he had long minor league baseball career, beginning in 1894 and ending in 1914.[2] Hallman died at the age of 74 in his hometown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and is interred at Mount Peace Cemetery.[1] He is the nephew of Bill Hallman, who also played baseball at the Major League level.

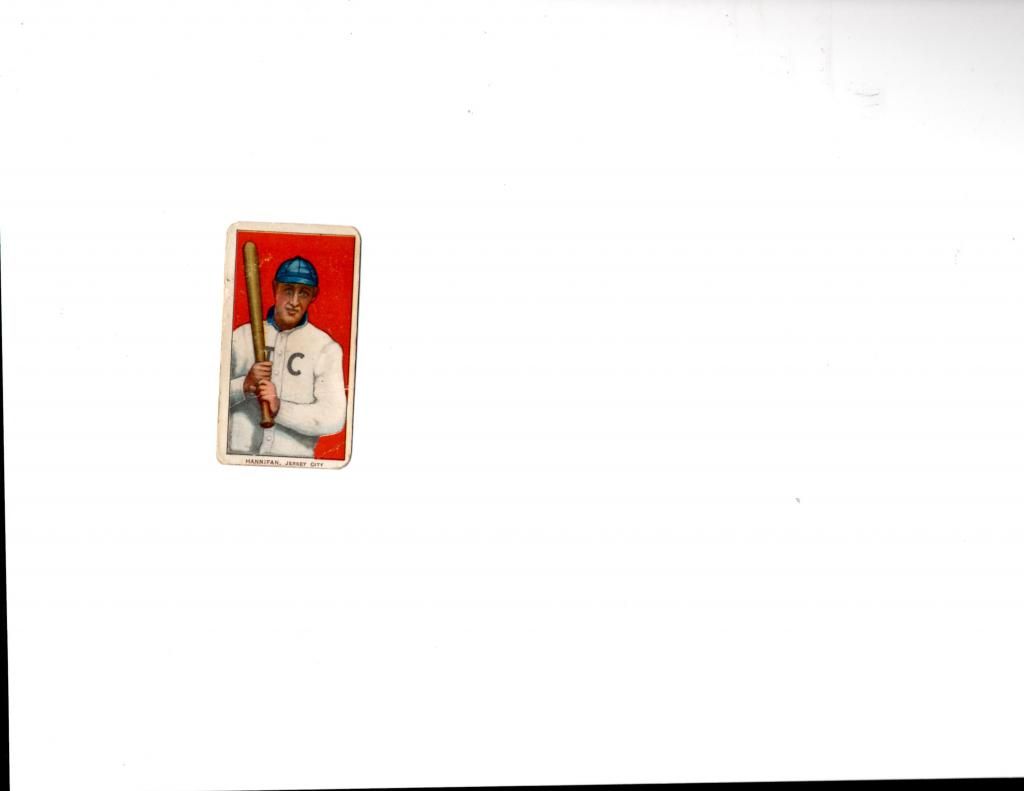

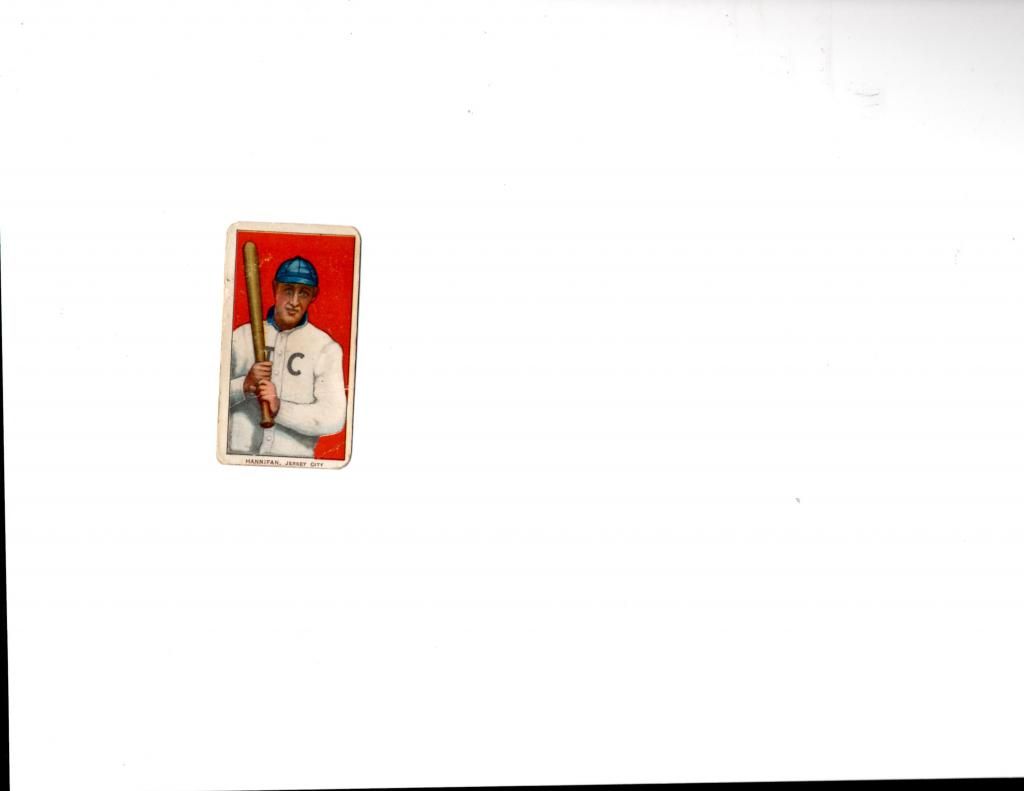

Jack Hannifan

John Joseph Hannifin (1883–1945) was an American Major League Baseball infielder. He played for the Philadelphia Athletics during the 1906 season, the New York Giants from 1906 to 1908, and the Boston Doves during the 1908 season

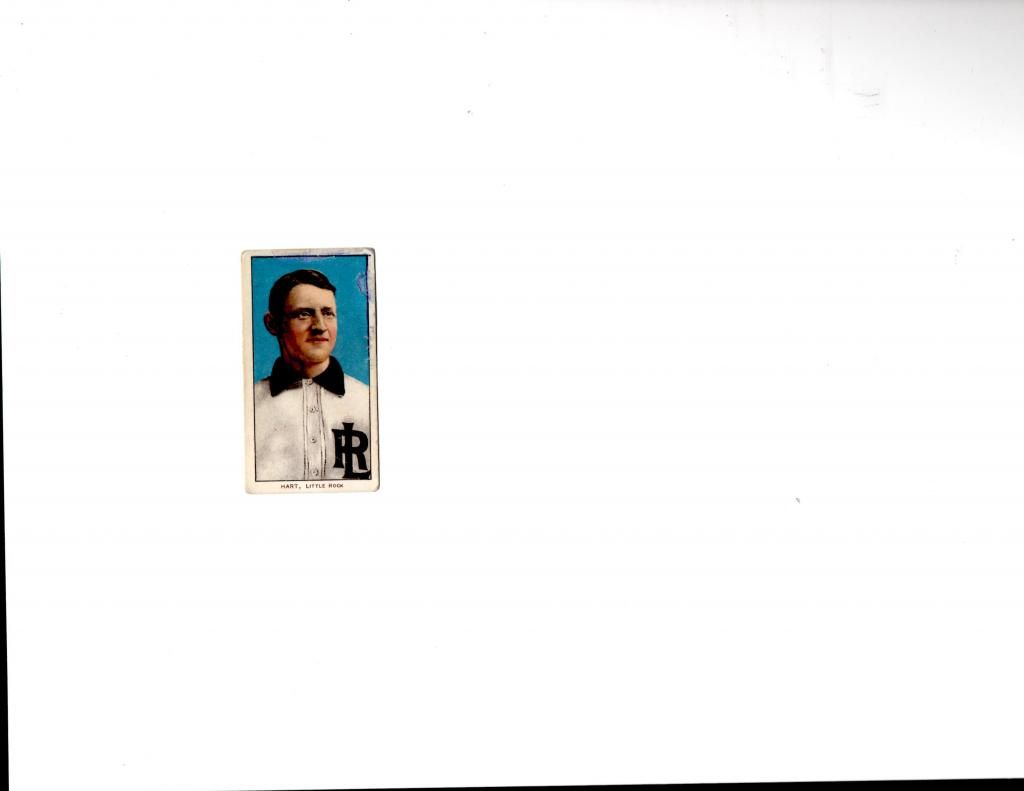

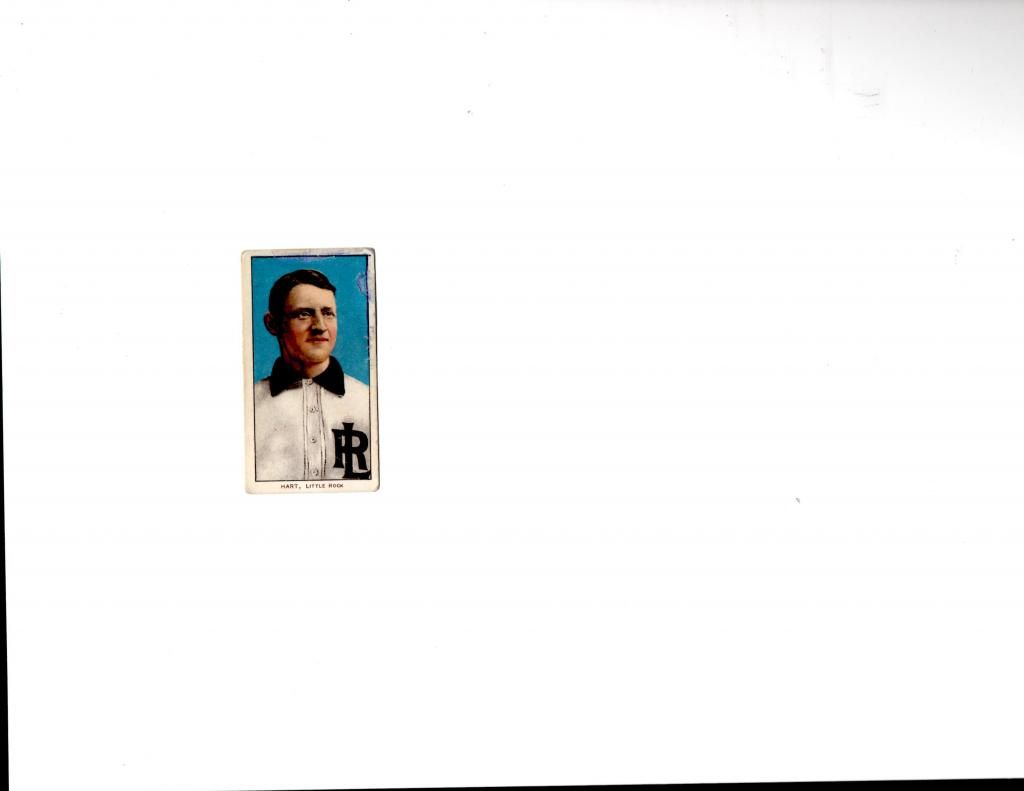

Bill Hart

William Franklin Hart (July 19, 1865 in Louisville, Kentucky – September 19, 1936 in Cincinnati, Ohio) was a professional baseball player who played pitcher in the Major Leagues from 1886 to 1901. He pitched in the American Association, National League and American League.

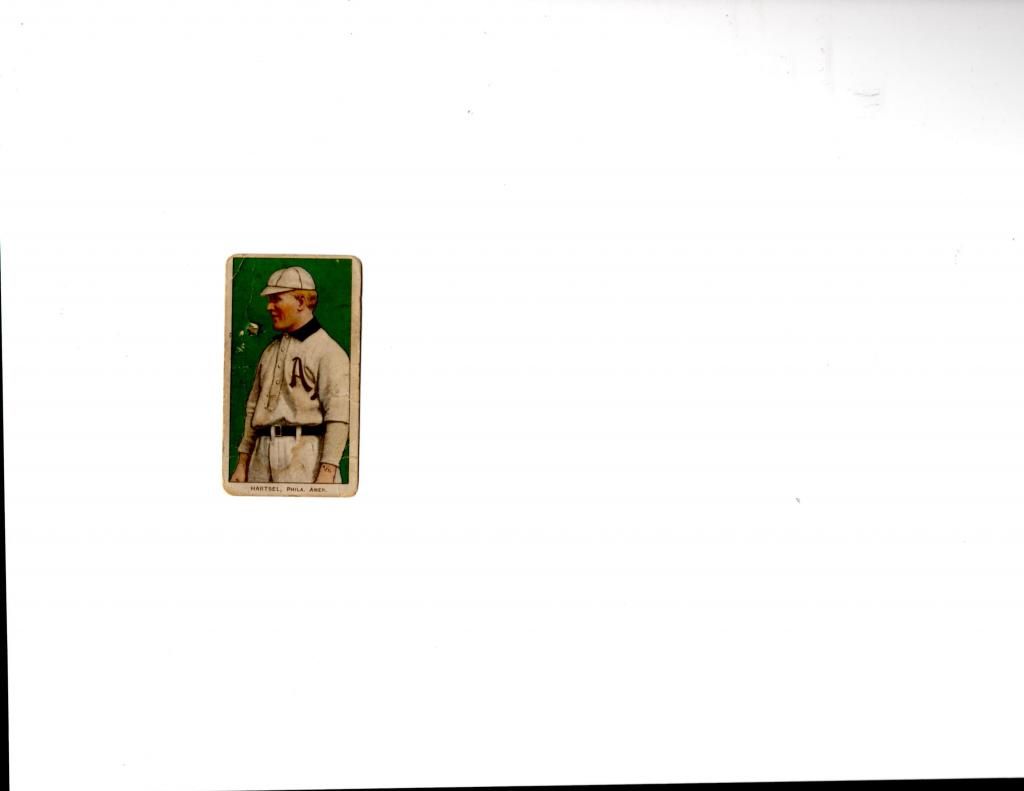

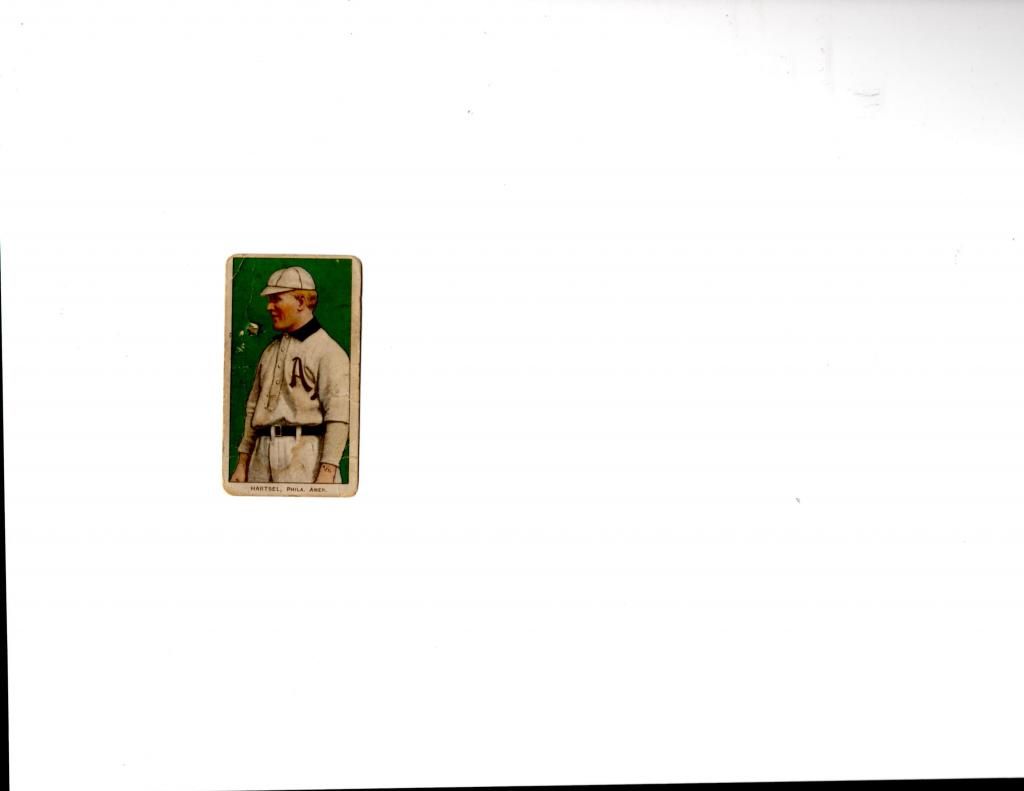

Topsy Hartsel

Tully Frederick "Topsy" Hartsel (June 26, 1874 – October 14, 1944) was an outfielder in Major League Baseball. He was born in Polk, Ohio, and played for the Louisville Colonels (1898–99), Cincinnati Reds (1900), Chicago Orphans (1901) and the Philadelphia Athletics (1902–11), with whom he won the World Series in 1910. On September 10, 1901, he established the record for putouts by a left fielder in a nine-inning game, with 11 against the Brooklyn Superbas.

Hartsel died in Toledo, Ohio, on October 14, 1944

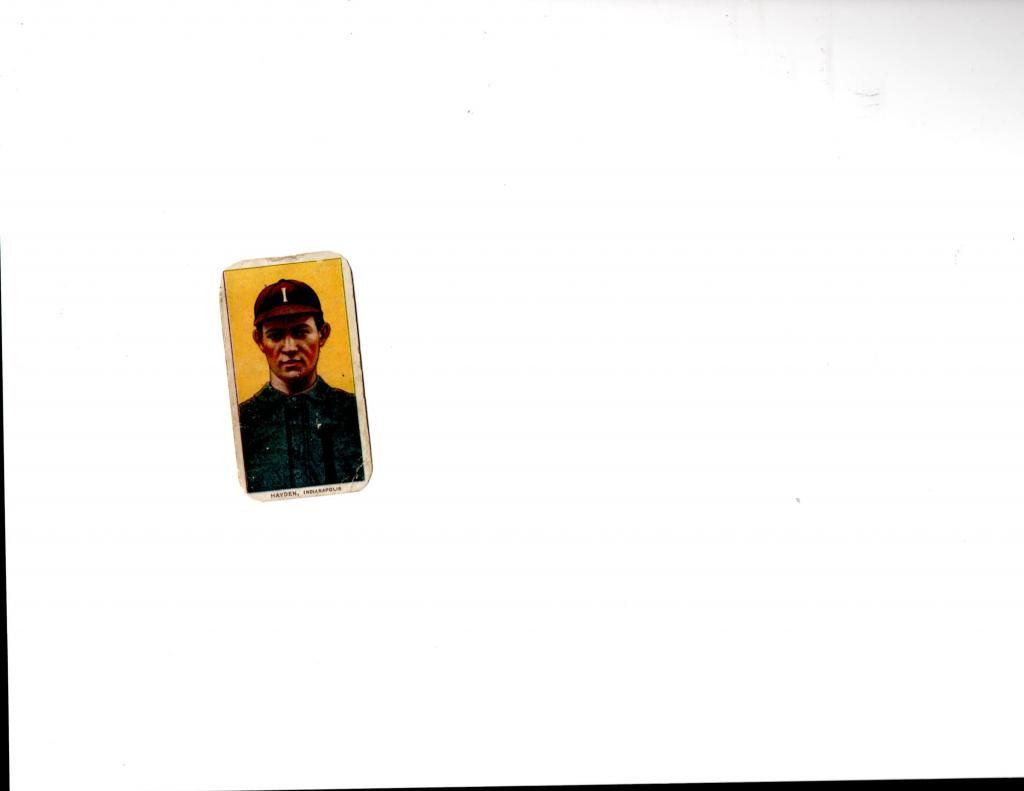

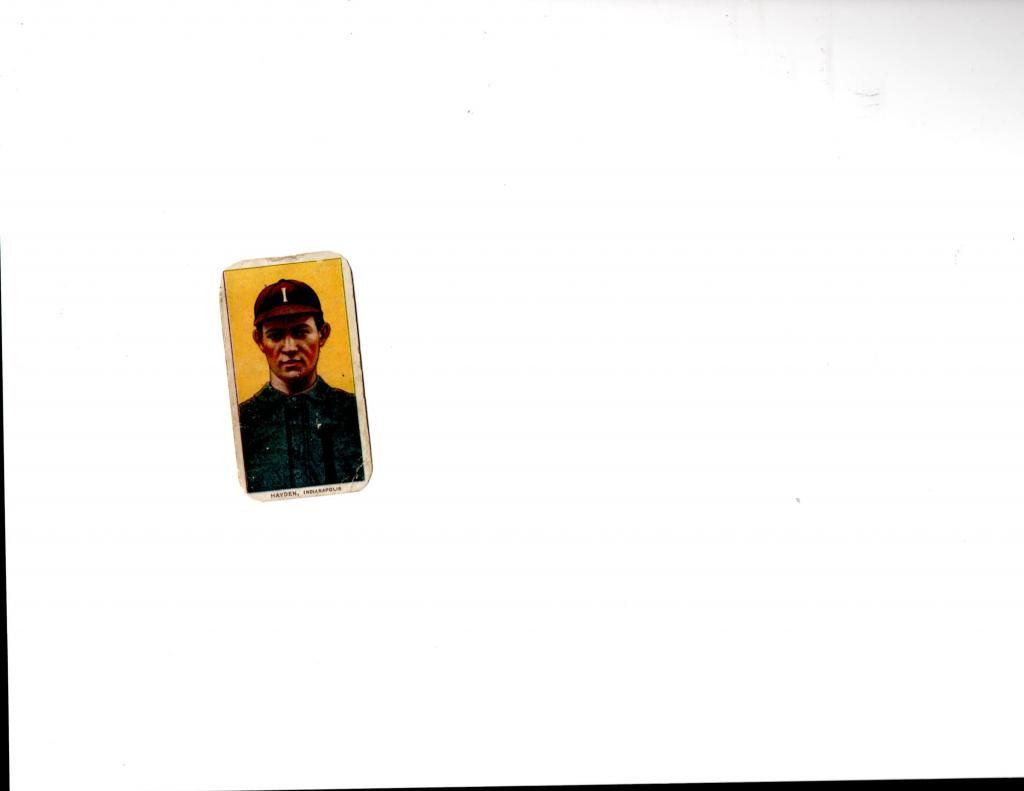

Jack Hayden ( Also a Football as a quarterback and a few other positions)

John Francis Hayden (October 21, 1880 – August 3, 1942) was a reserve outfielder in Major League Baseball who played between the 1901 and 1908 seasons for the Philadelphia Athletics (1901), Boston Americans (1906) and Chicago Cubs (1908). A native of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, he attended college at Villanova University.

In a three-season career, Hayden was a .251 hitter (145-for-578) with one home run and 33 RBI in 147 games, including 60 runs, 14 doubles, eight triples, and 11 stolen bases. He made 146 outfield appearances at right field (112), left (30) and center (4). He later became the manager for the Louisville Colonels.

During a game against the Yankees at Hilltop Park on September 11, 1906, Americans second baseman Hobe Ferris, notorious for his hard style of play, got into a nasty fight with Hayden, who was accused by Ferris of lackadaisical play. After they were separated, Hayden returned to the bench and Ferriss ran after him and kicked him in the face. Both were ejected from the game, but Ferris refused to go. Two policemen escorted him to the clubhouse and later was arrested for assault. After that, Ferris was suspended for the remainder of the season. This was the first time in major league history that teammates had been ejected for fighting each other.

Outside of baseball, Hayden also played American football professionally and at the college level as a quarterback. Over the span of his career, Hayden played for Villanova, the Penn Quakers, University of Maryland, Maryland Athletic Club and finally the Philadelphia Athletics of the 1902 National Football League. His football career continued in 1903 with the Franklin Athletic Club. In 1905, he was in the line-up for the Massillon Tigers of the "Ohio League". A year later he jumped to the rivial Canton Bulldogs after being offered more money to play there by former Franklin teammate, Blondy Wallace. In 1906, he took part in the two football games between Canton and Massillon that were centered around the Canton Bulldogs–Massillon Tigers betting scandal. During the first game of that series against Massillon, Jack ran the team faultlessly and dropkicked a 35-yard field goal in the first half to put the Bulldogs in front 4–0 (field goals were worth 4 points at the time) and was one of the heroes of the game. However in the team's second game against Massillon, six punts sailed over his head, while playing the safety position.

Hayden died in Havertown, Pennsylvania, at age 61.

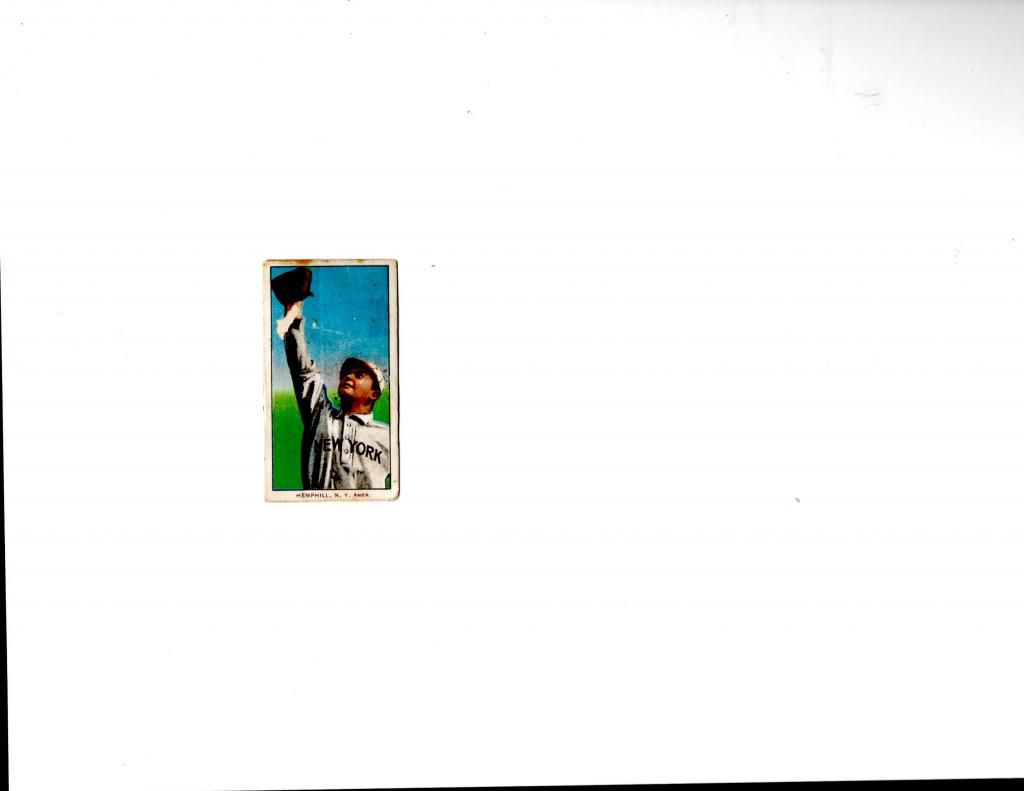

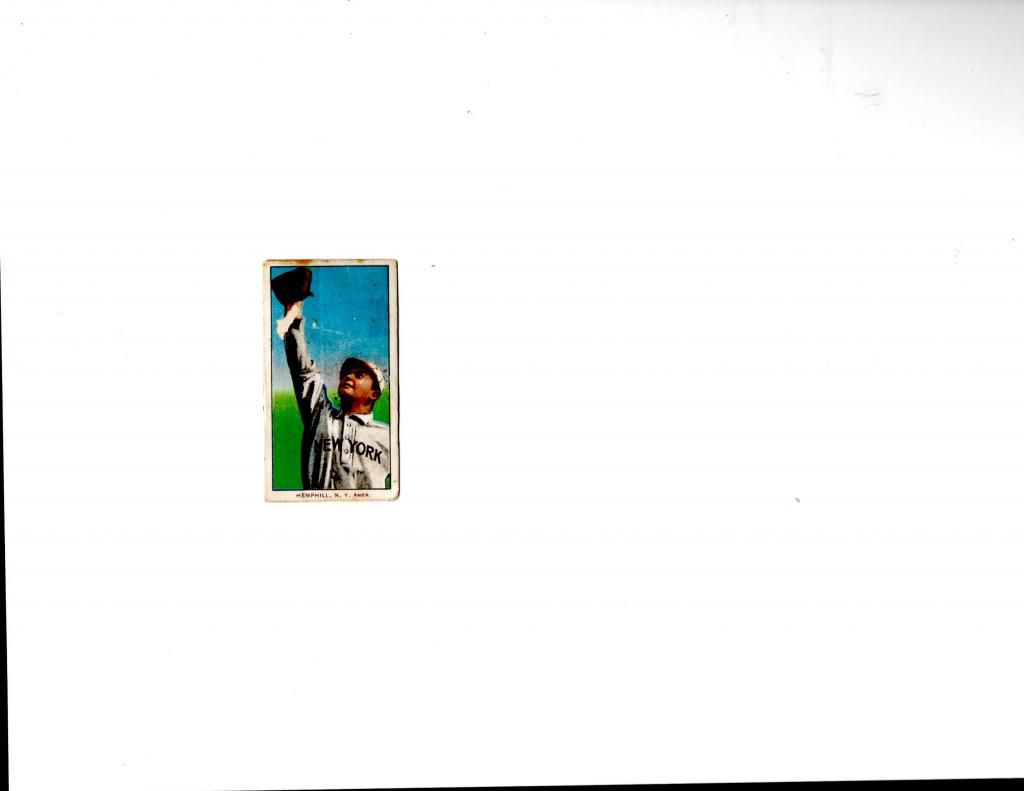

Charlie Hemphill

Hemphill was born in Greenville, Michigan. His younger brother, Frank Hemphill, also was a major league outfielder.

Basically a line-drive hitter, Hemphill entered the majors in 1899 with the St. Louis Perfectos, appearing in 11 games for them before joining the Cleveland Spiders during the midseason. The St. Louis and Cleveland clubs, both owned by the Robison Brothers, proceeded to transfer the Spiders' top players to St. Louis, leaving Cleveland with a truly awful club—they finished 20-134, the worst mark in major league history. The Spiders folded at the end of the season, and Hemphill went to the Kansas City Blues of the newly created American League in 1900; the AL was still considered a minor league that year.

In 1901, Hemphill became the first Opening Day right fielder in the Boston Red Sox' franchise history; after that, he played with the Cleveland Bronchos (1902), St. Louis Browns (1902–07) and New York Highlanders (1908–11). His most productive season came in 1902, when he hit a combined .308 batting average with Cleveland and St. Louis. He enjoyed another good season with the 1908 Yankees, hitting .298 (fourth in AL) with a career-high 42 stolen bases. His final season in the majors came with New York in 1911, where he was a teammate of Chet Hoff, in what would be Hoff's only big-league campaign. Hoff wound up being the longest-lived player in MLB history, finally passing away at age 107 in 1998—nearly a century after his old teammate Hemphill first played in the majors.

In an 11-season career, Hemphill was a .271 hitter (1230-for-4541) with 22 home runs and 421 RBI in 1242 games, including 580 runs, 117 doubles, triples, 207 stolen bases, and a .337 on-base percentage. In 1175 outfield appearances, he played at center field (607), right (525) and left (45). He also played three games at second base.

Hemphill died in Detroit, Michigan, at age 77.

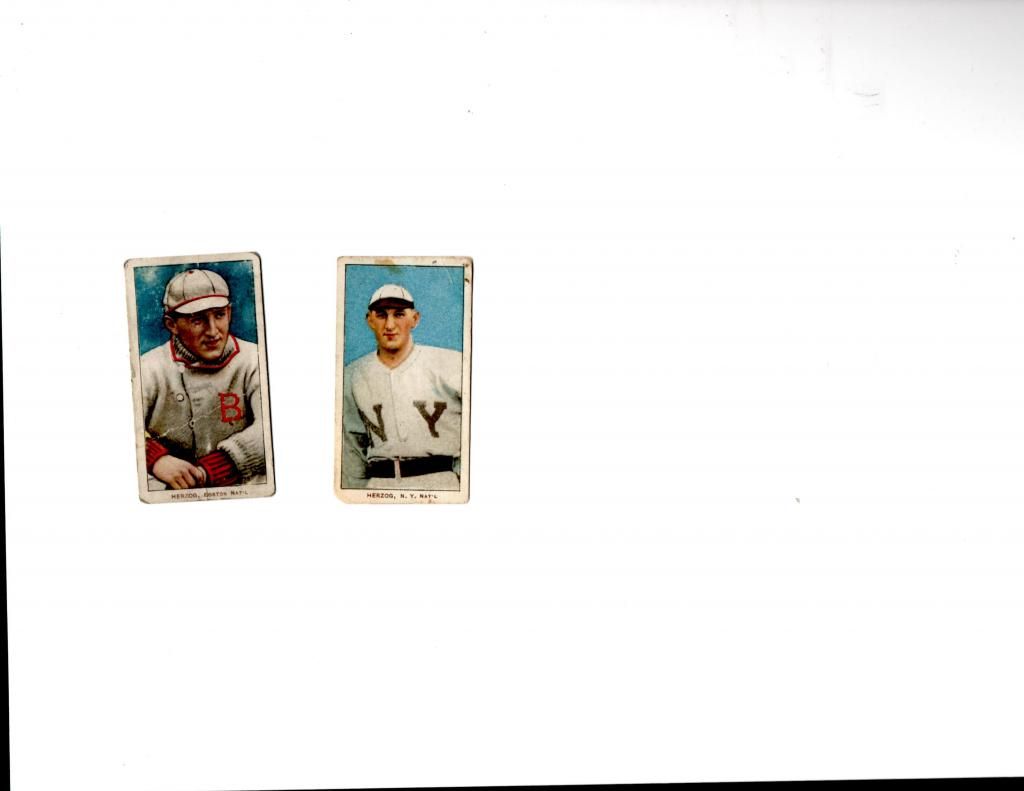

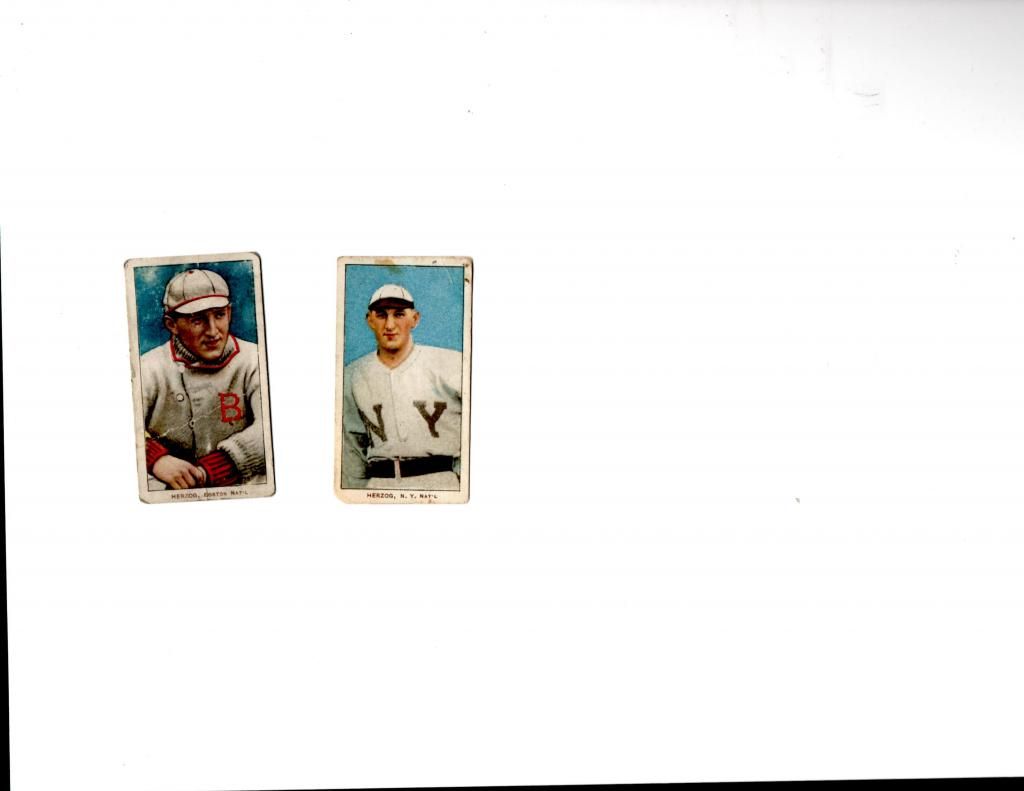

Buck Herzog

Charles Lincoln "Buck" Herzog (July 9, 1885 – September 4, 1953) was an American infielder and manager in Major League Baseball who played for four National League clubs between 1908 and 1920. He played for the New York Giants, the Boston Braves, the Cincinnati Reds, and the Chicago Cubs. He was a lifelong resident of Maryland: he was born and died in Baltimore, but spent a considerable amount of his retirement years in Ridgely. He died at age 68 in Baltimore.

Recently his carriage house was saved from demolition and moved to the center of Ridgely.

![[Image: roughdraft_edited-1.jpg]](http://i51.photobucket.com/albums/f354/blayneroessler/roughdraft_edited-1.jpg)

Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-13-2015, 10:59 PM

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Herzog

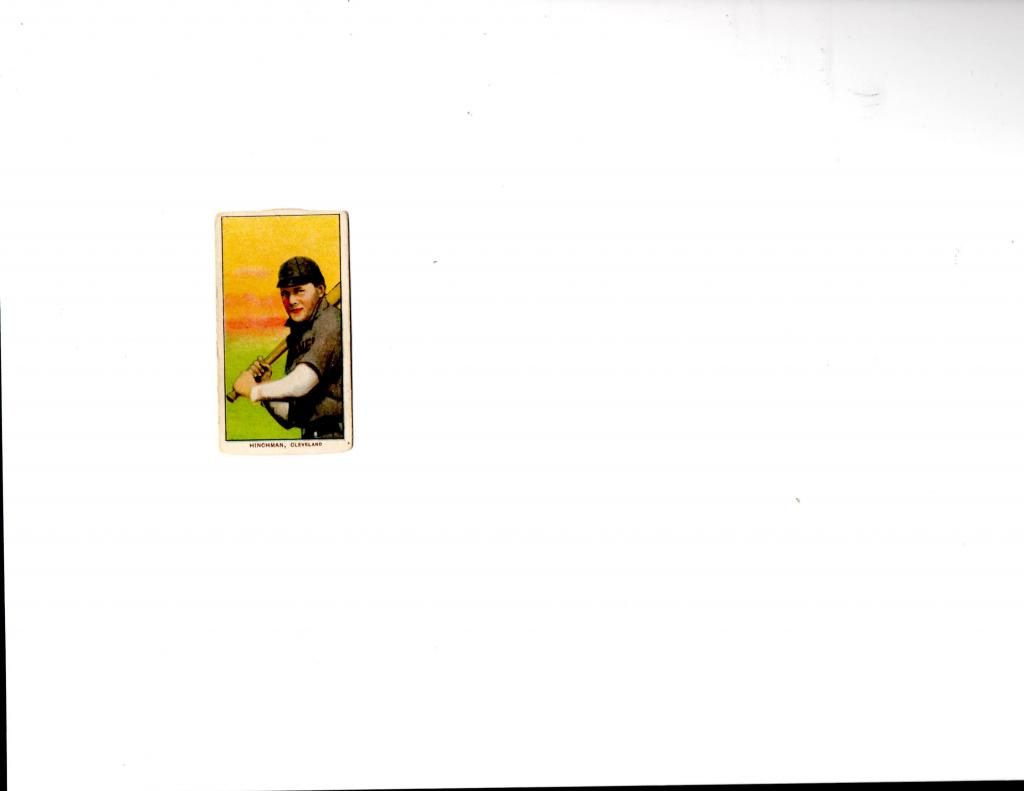

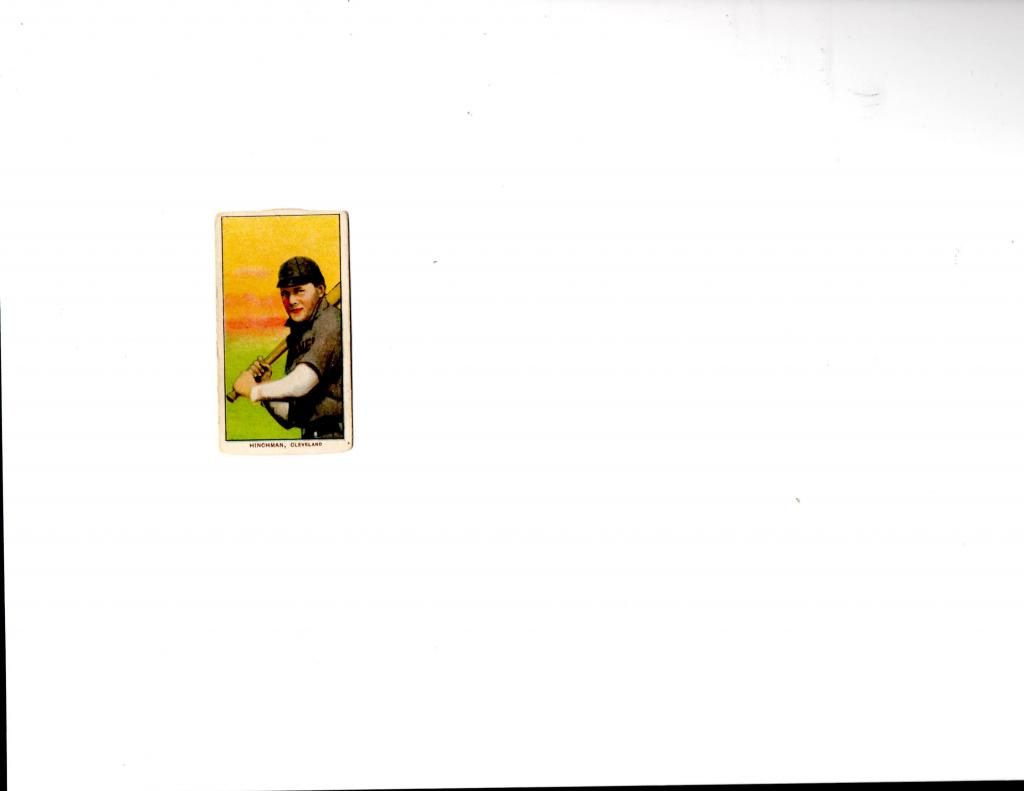

Bill Hinchman

William White Hinchman (April 4, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – February 20, 1963 in Columbus, Ohio), was a professional baseball player who played outfielder in the Major Leagues from 1905 to 1920. He played for the Cincinnati Reds, Cleveland Naps, and Pittsburgh Pirates.

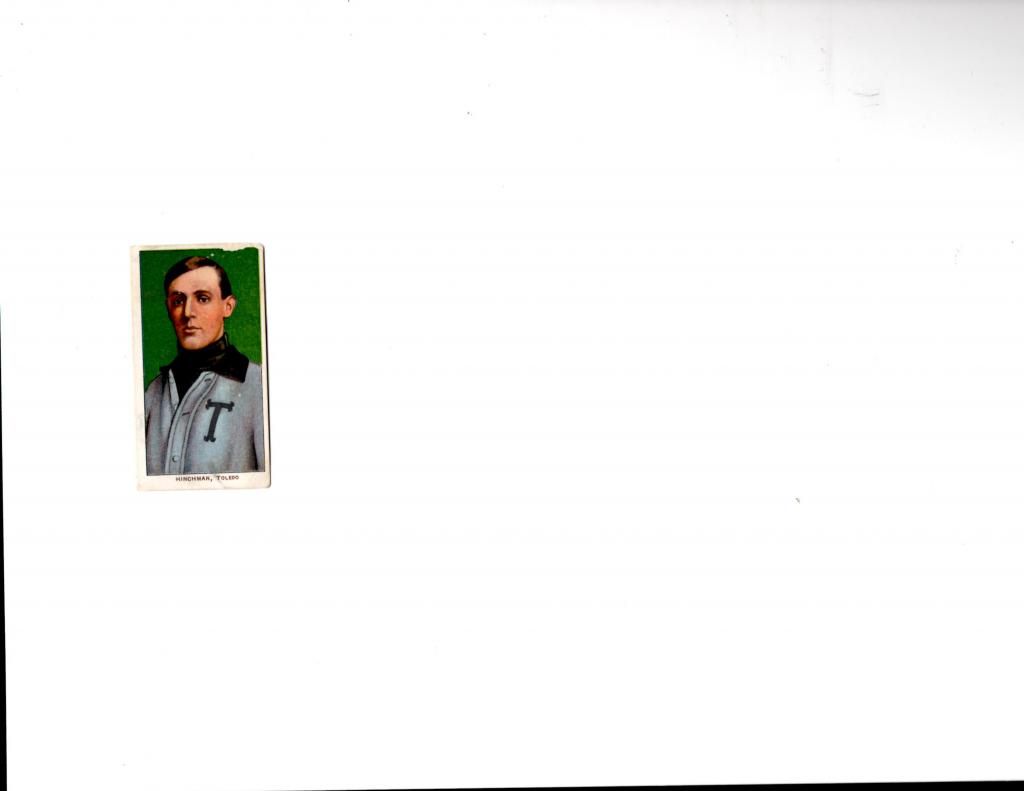

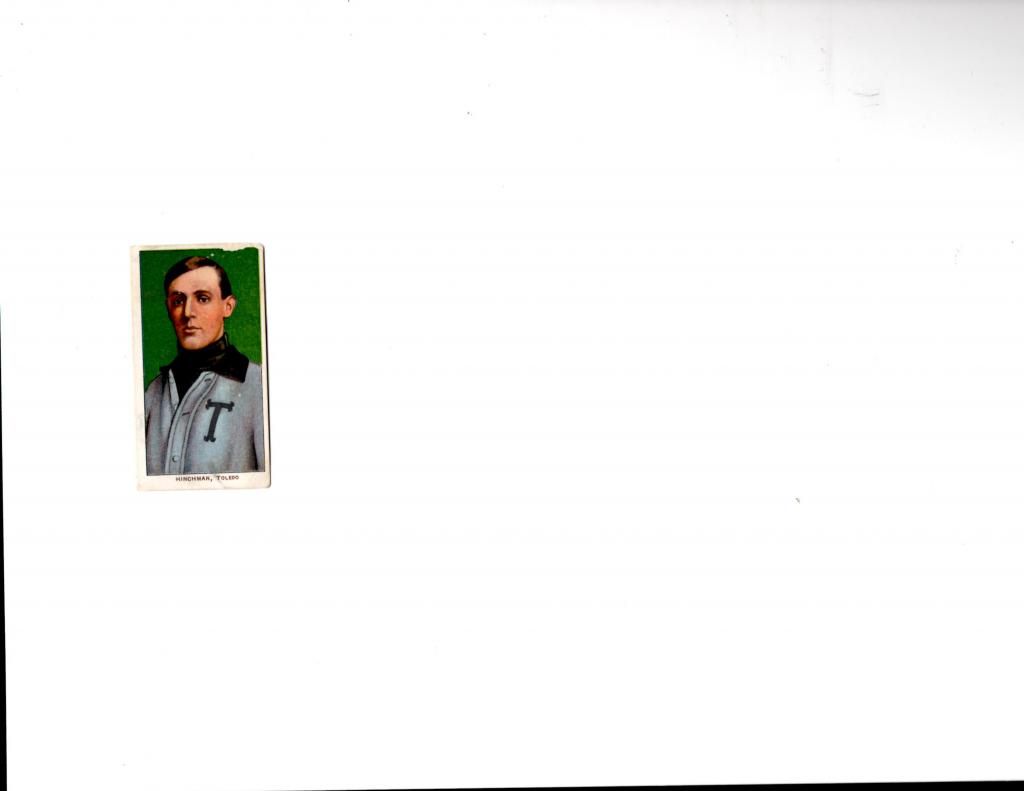

Harry Hinchman

Harry Sibley Hinchman (August 4, 1878 – January 19, 1933) was a Major League Baseball second baseman who played for one season. He played in 15 games for the Cleveland Naps during the 1907 Cleveland Naps season.

In contrast to his one season in the major leagues, Hinchman played for 18 seasons in the minor leagues. He began his professional career with the Ilion Typewriters of the New York State League in 1902. His best year as a player in 1915 with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. That year he had a .326 batting average. His last year as a player was in 1921 with the Chambersburg Maroons of the class D Blue Ridge League.

In addition to being a player, he also managed several minor league teams from 1910 to 1932 (to 1921 as a player/manager and from 1923 solely as manager

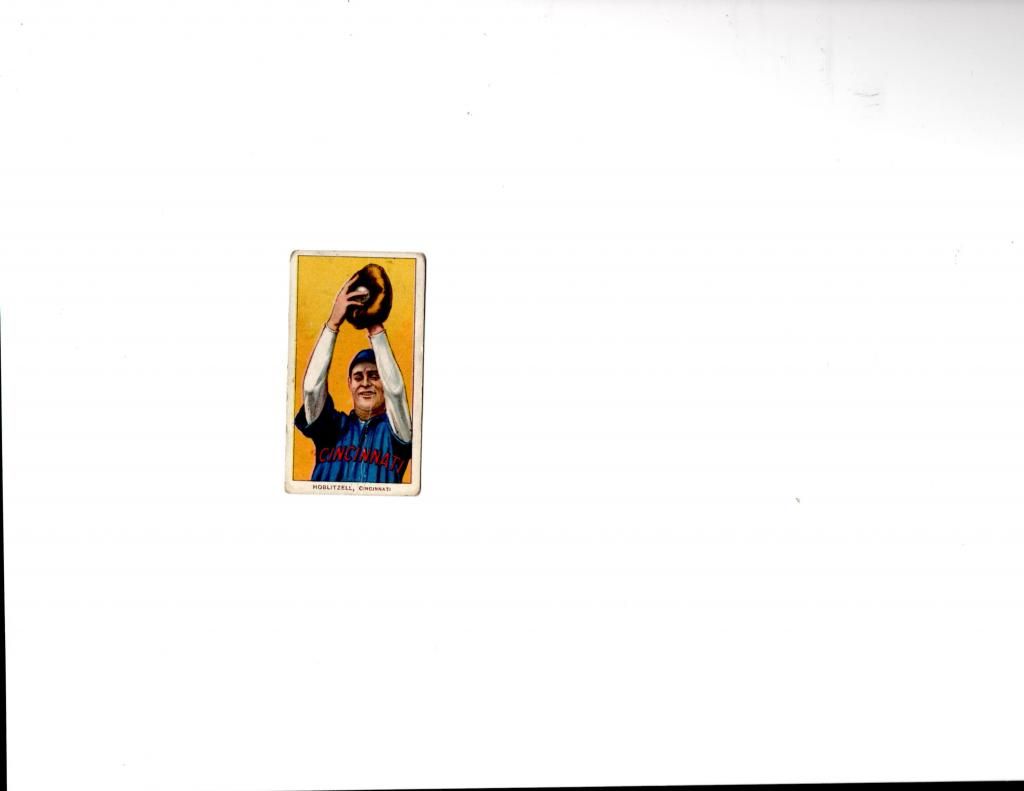

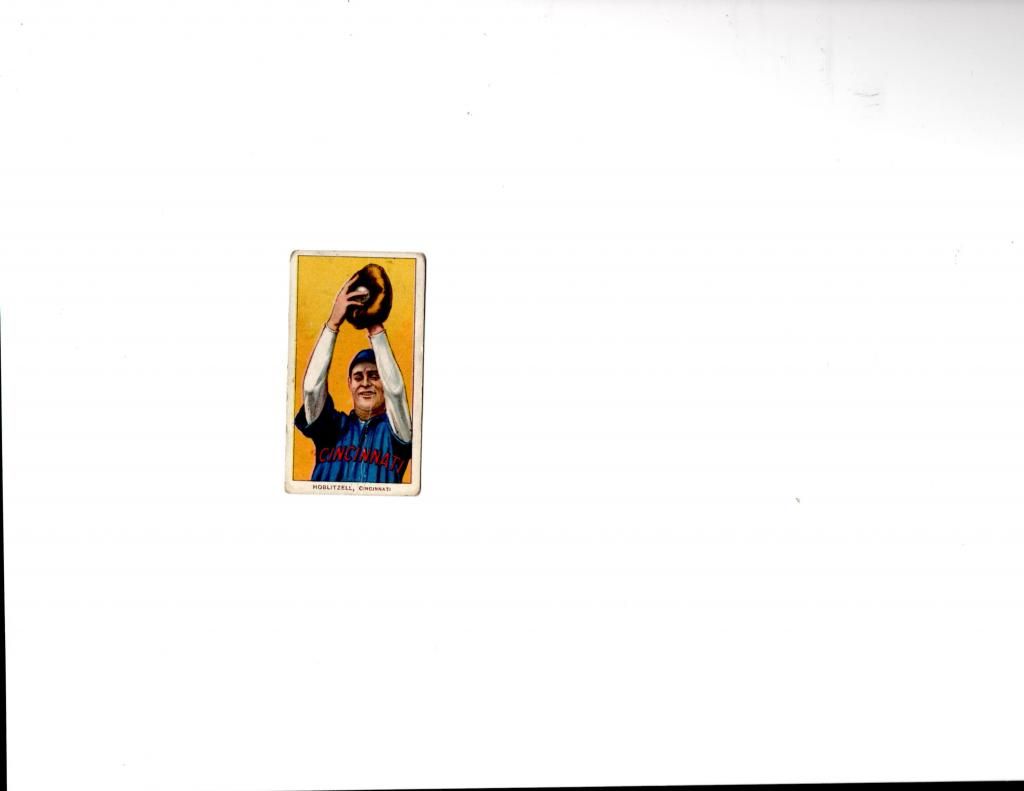

Doc Hoblitzell-( WW1 and a dentist)

Richard Carleton "Dick" Hoblitzell (October 26, 1888 in Waverly, West Virginia – November 14, 1962 in Parkersburg, West Virginia) played first base in the major leagues from 1908 to 1918. He played for the Cincinnati Reds and Boston Red Sox. Hoblitzel was the National League at-bats leader in 1910 and 1911 and Cincinnati's Most Valuable Player in 1911. Nicknamed "Doc" by his teammates, Hoblitzell's baseball career was cut short with his World War I induction into the US Army as a dentist in 1918. He graduated from the University of Pittsburgh

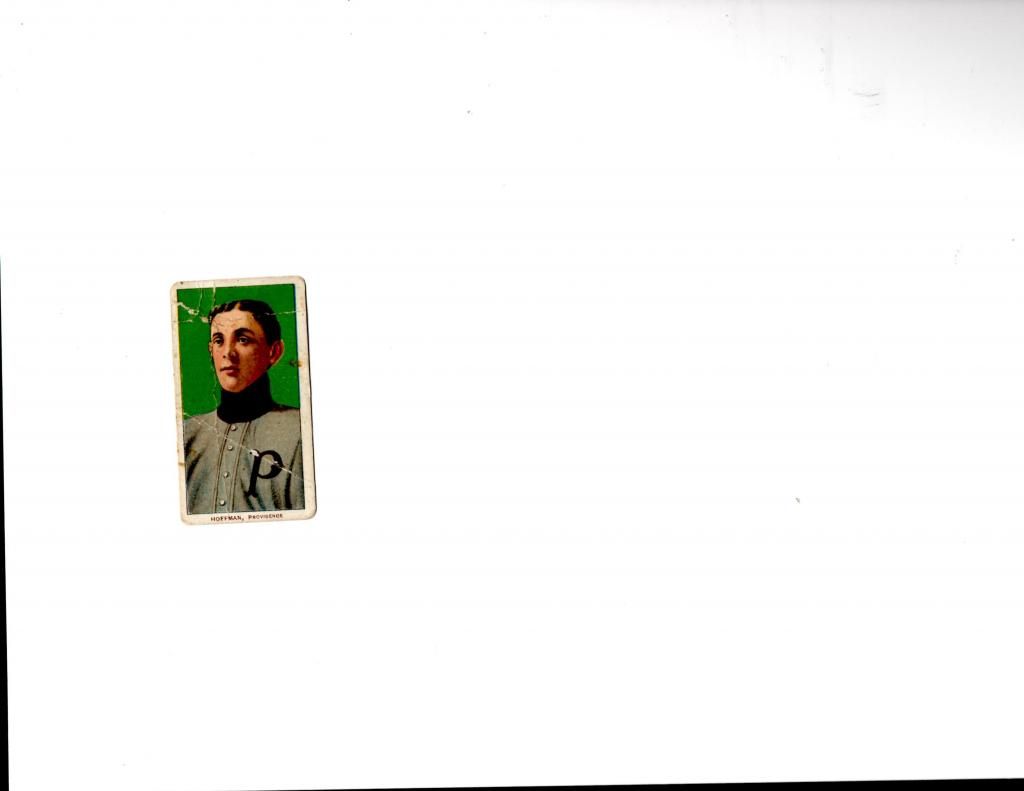

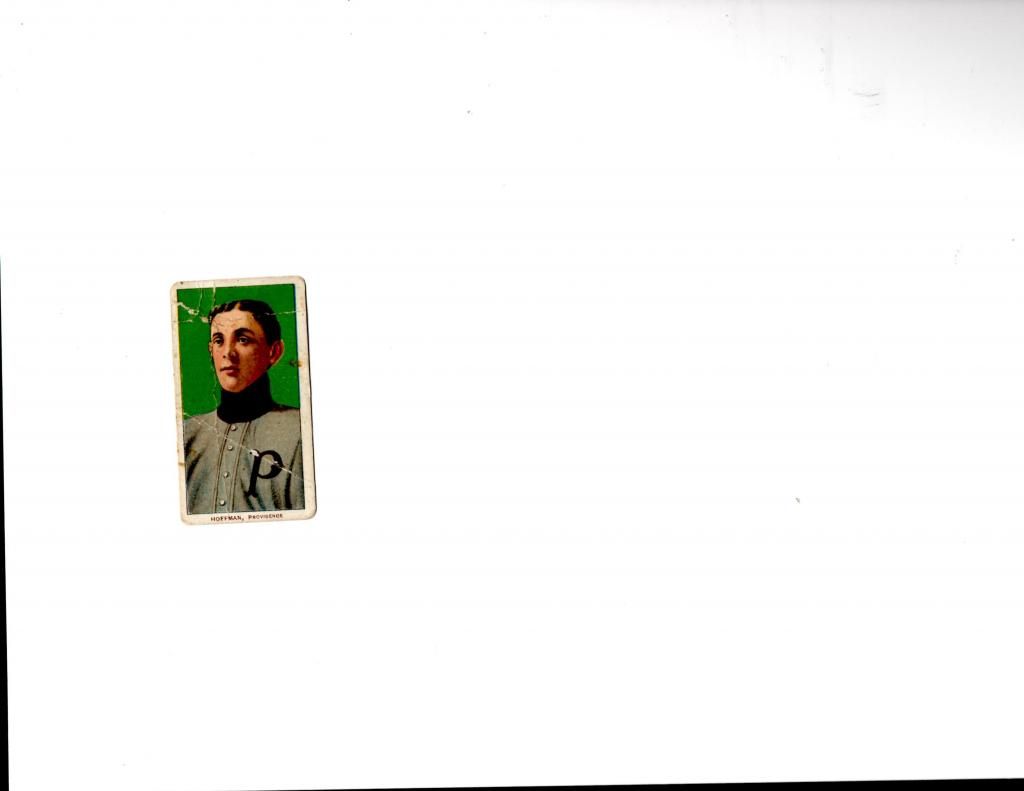

Izzy Hoffman

Harry C. Hoffman (1875–1942) was a Major League Baseball outfielder who played for the Washington Senators in 1904 and the Boston Doves in 1907

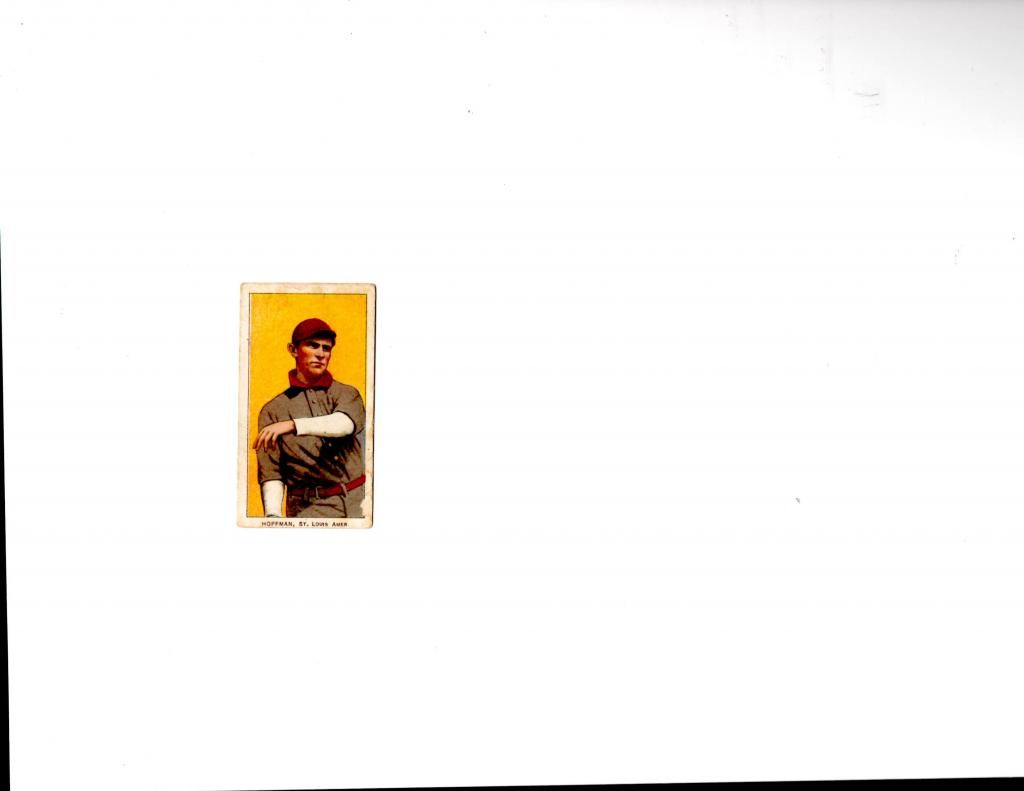

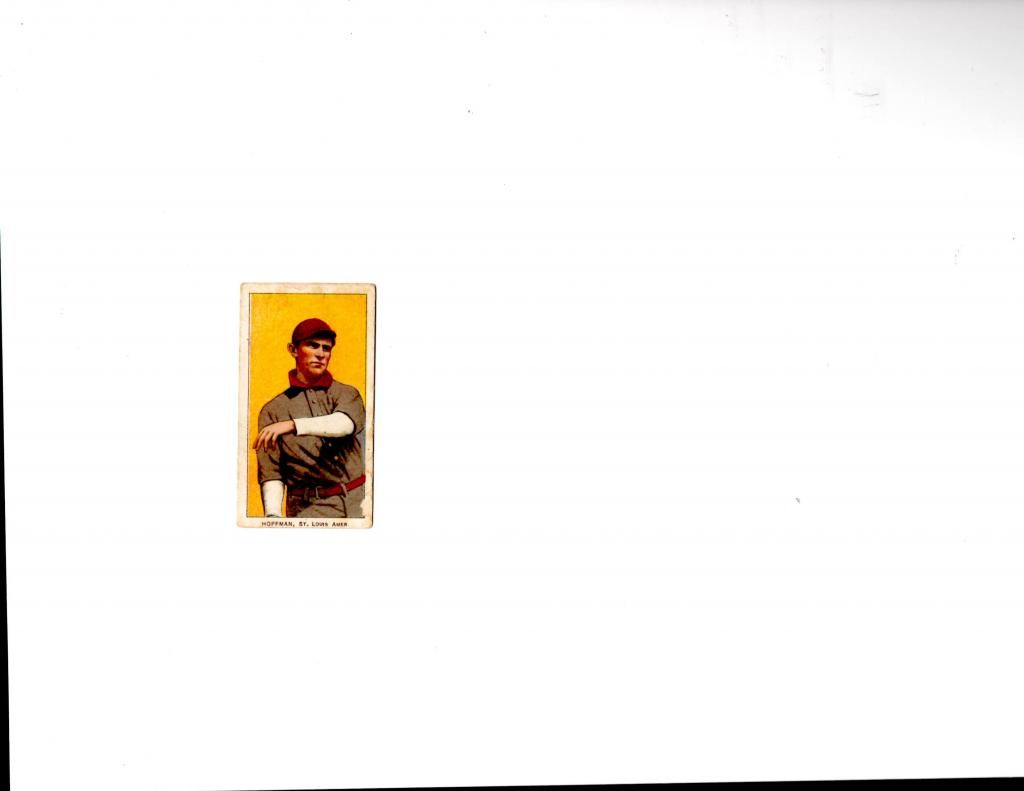

Danny Hoffman ( mean guy he killed my favorite animal a Horse, but it was an accident)

Danny Hoffman (March 2, 1880 in Canton, Connecticut – March 22, 1922), was a professional baseball player who played outfield in the Major Leagues from 1903 to 1911. During his career Hoffman played for the Philadelphia Athletics, New York Highlanders, and St. Louis Browns.

When playing for the Springfield Ponies in 1902, they were playing a road game against Bridgeport. Hoffman batted a ball into the outfield, which struck and killed a horse.[1]

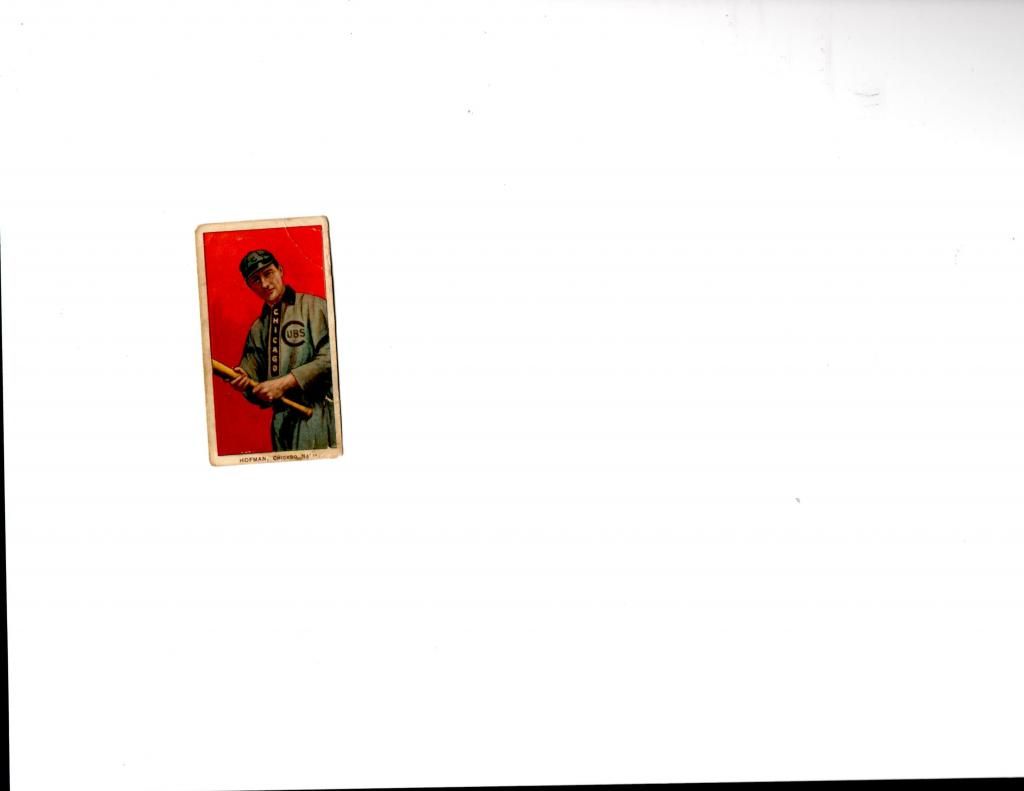

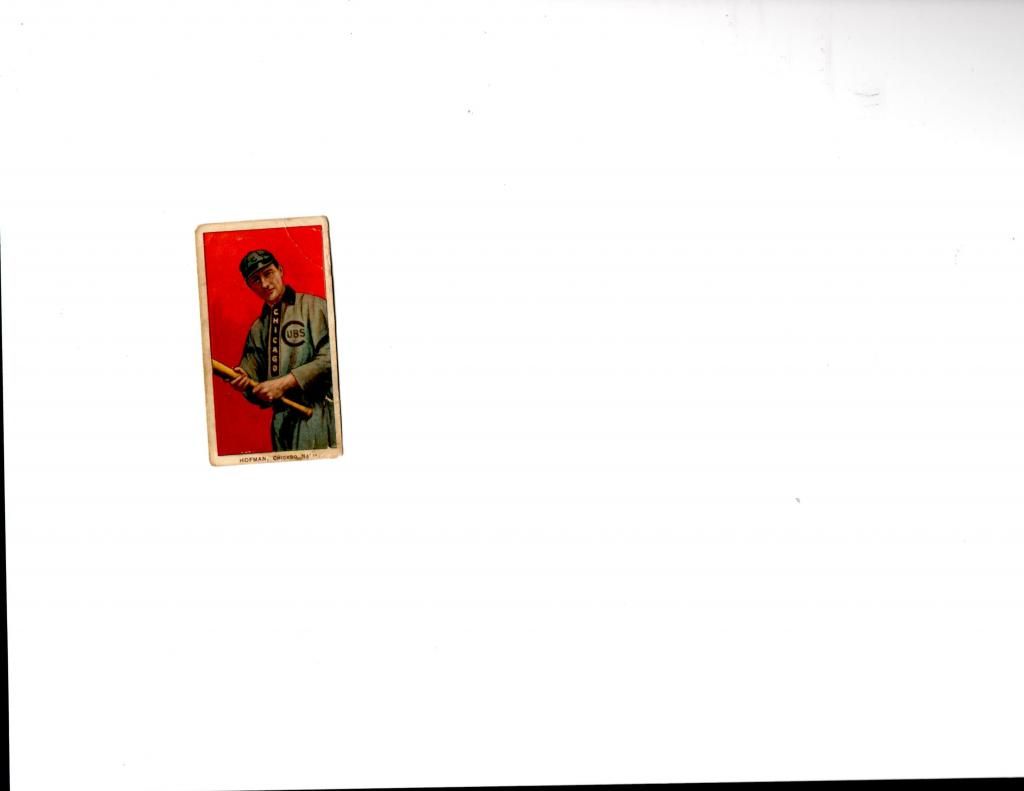

Solly Hofman

Arthur Frederick "Solly" Hofman (born October 29, 1882 in St. Louis, Missouri; died March 10, 1956 in St. Louis, Missouri) was a Major League Baseball player from 1903 to 1916. He played the majority of his 1,175 professional games in the outfield.

His nickname was "Circus Solly". Some attribute this name to a comic strip of the era, while others attribute it to spectacular catches while fielding.[1]

He is considered by some to be the first great utility player in baseball due to his versatility.[

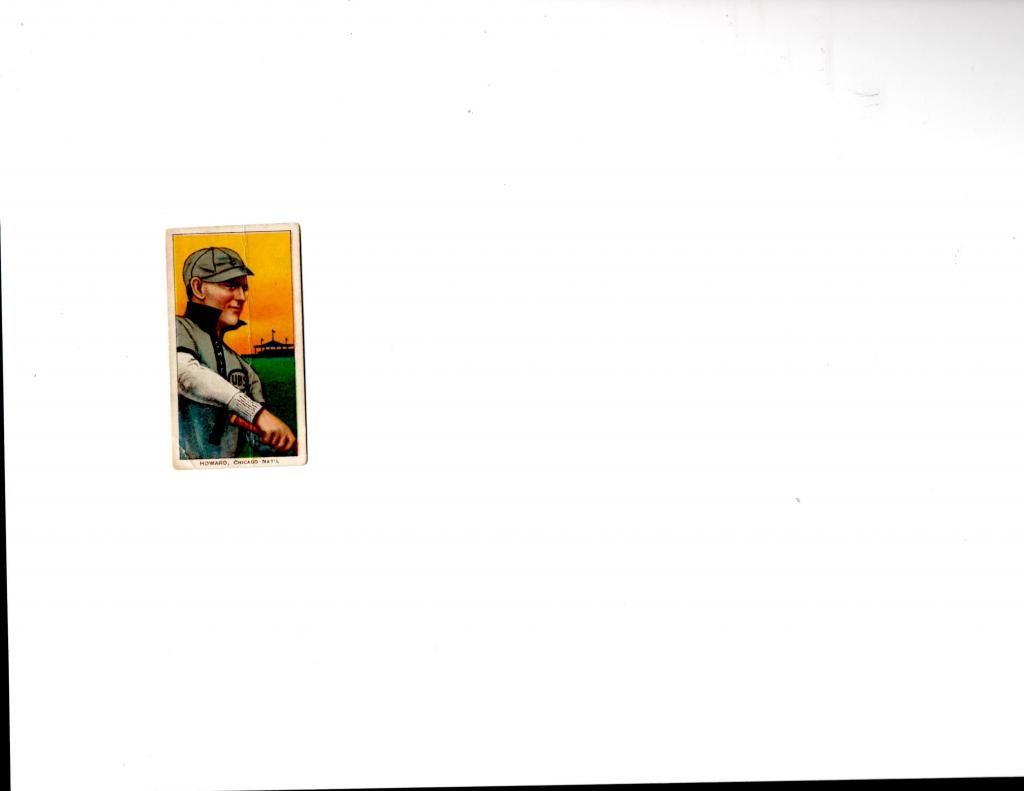

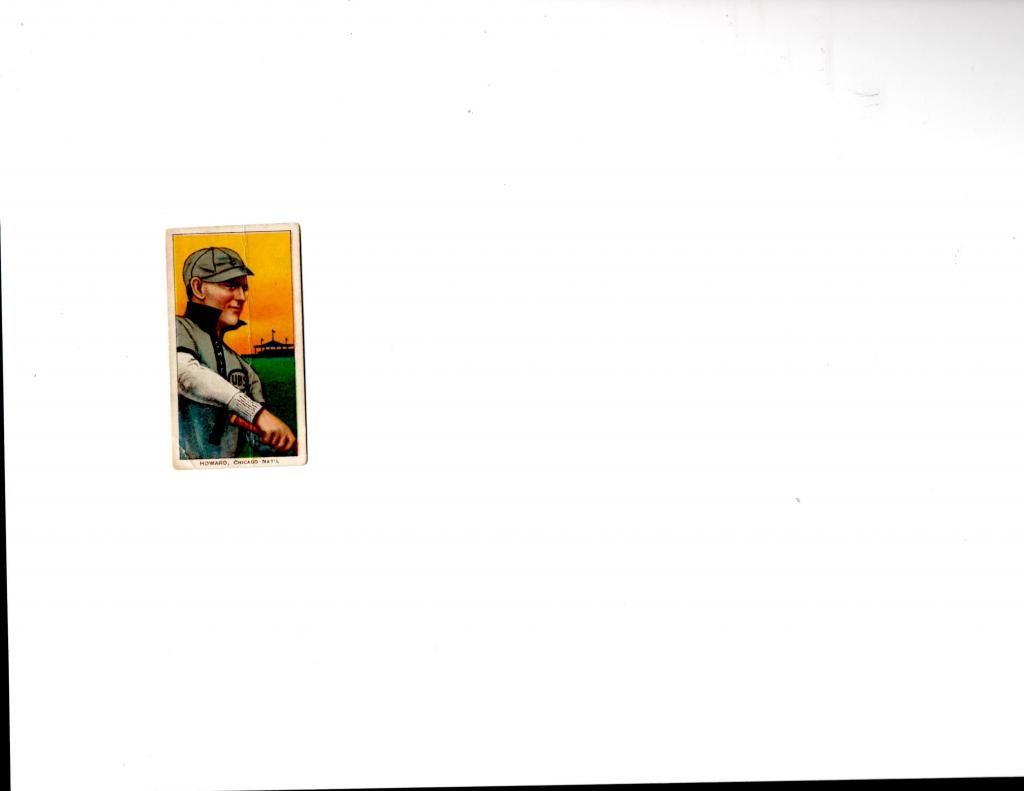

Del Howard

George Elmer "Del" Howard (December 24, 1877 in Kenney, Illinois – December 24, 1956 in Seattle, Washington) was a Major League Baseball player from 1905 to 1909. He would play for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Boston Beaneaters/Doves, and Chicago Cubs. Howard appeared in 536 games and retired with six home runs and a lifetime .263 batting average.[1]

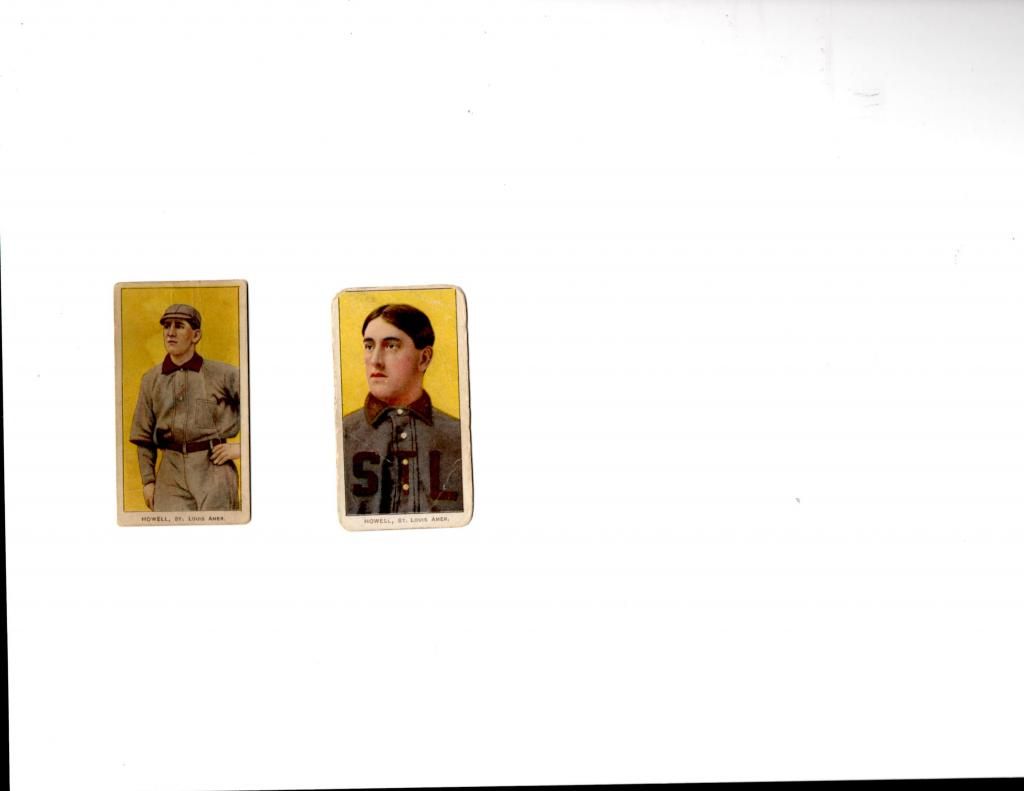

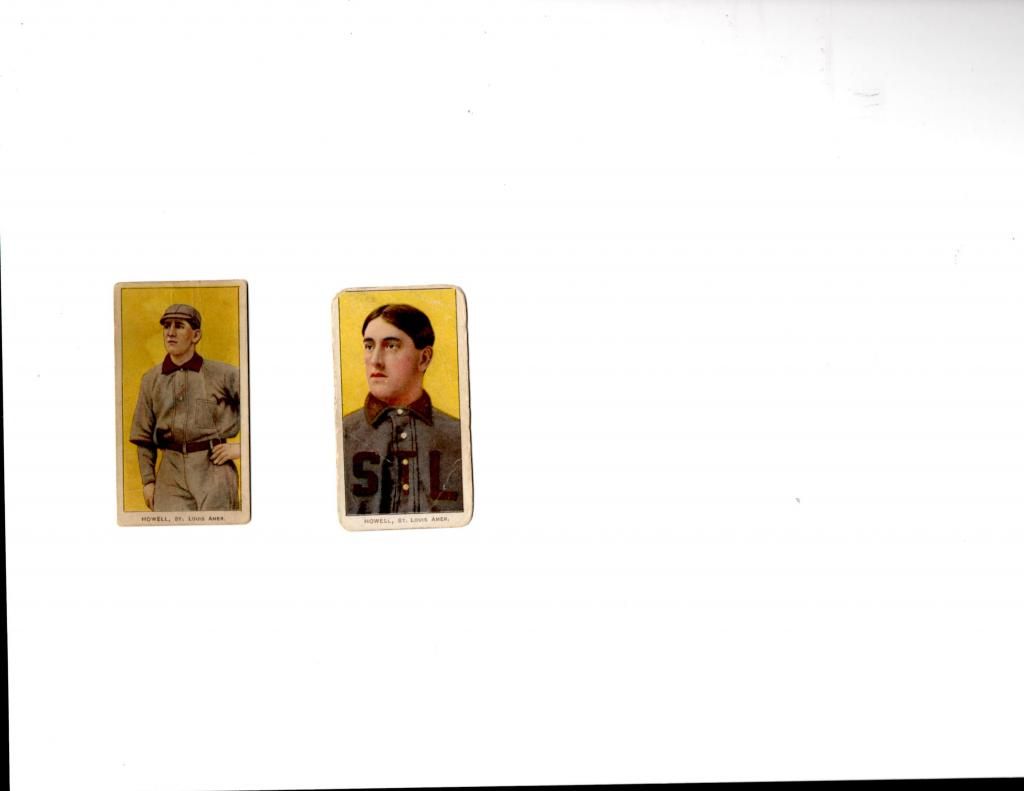

Harry Howell

Harry Taylor Howell (November 14, 1876 – May 22, 1956) born in New Jersey was a pitcher for the Brooklyn Bridegrooms/Brooklyn Superbas (1898 and 1900), Baltimore Orioles (1899), Baltimore Orioles/New York Highlanders (1901–03) and St. Louis Browns (1904–10).

He helped the Superbas win the 1900 National League Pennant.

He led the National League in Games Finished in 1900 (10) and the American League in 1903 (10) and led the American League in Complete Games (35) in 1905.

He currently ranks 82nd on the MLB All-Time ERA List (2.74), 87th on the All-Time Complete Games List (244) and 68th on the Hit Batsmen List (97).

He is also the Baltimore Orioles Career Leader in ERA (2.06).

In 13 seasons he had a 131–146 Win-Loss record, 340 Games (282 Started), 244 Complete Games, 20 Shutouts, 53 Games Finished, 6 Saves, 2,567 ⅔ Innings Pitched, 2,435 Hits Allowed, 1,158 Runs Allowed, 781 Earned Runs Allowed, 27 Home Runs Allowed, 677 Walks, 986 Strikeouts, 97 Hit Batsmen, 53 Wild Pitches, 7,244 Batters Faced, 1 Balk, 2.74 ERA and a 1.212 WHIP.

He died in Spokane, Washington at the age of 79.

Scandal

Howell, along with the Jack O'Connor, the Browns player-manager, was involved in the scandal surrounding efforts to help Cleveland's Nap Lajoie win the batting title and the associated 1910 Chalmers Award over Ty Cobb in the last two games of the season, a doubleheader at Sportsman's Park. Cobb was leading Lajoie .385 to .376 in the batting race going into that last day. O'Connor ordered rookie third baseman Red Corriden to station himself in shallow left field to allow what otherwise would be routine infield ground outs to be base hits. Lajoie bunted five straight times down the third base line and made it to first easily. On his last at-bat, Lajoie reached base on a fielding error, officially giving him a hitless at-bat and lowering his average. O'Connor and Howell tried to bribe the official scorer, a woman, to change the call to a hit, offering to buy her a new wardrobe. Cobb won the batting title by less than one point over Lajoie, .385069 to .384095. The resulting outcry triggered an investigation by American League president Ban Johnson, who declared Cobb the rightful winner of the batting title (though Chalmers awarded cars to both players). At his insistence, Browns' owner Robert Hedges fired both O'Connor and Howell, and released them as players; both men were informally banned from baseball for life.[1]

In 1981, however, research revealed that one game was counted twice for Cobb when he went 2-for-3. As a result, his 1910 batting statistics should have been shown as 194-for-506 and .383399, less than 0.7 points behind Lajoie at 227-for-591

Miller Huggins (Lawyer)

Miller James Huggins (March 27, 1879 – September 25, 1929) was an American professional baseball player and manager. Huggins played second base for the Cincinnati Reds (1904–1909) and St. Louis Cardinals (1910–1916). He managed the Cardinals (1913–1917) and New York Yankees (1918–1929), including the Murderers' Row teams of the 1920s that won six American League (AL) pennants and three World Series championships.

Huggins was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. He received a degree in law from the University of Cincinnati, where he was also captain on the baseball team. Rather than serve as a lawyer, Huggins chose to pursue a professional baseball career. He played semi-professional and minor league baseball from 1898 through 1903, at which time he signed with the Reds.

As a player, Huggins was adept at getting on base. He was also an excellent fielding second baseman, earning the nicknames "Rabbit", "Little Everywhere", and "Mighty Mite" for his defensive prowess and was later considered an intelligent manager who understood the fundamentals of the game. Despite fielding successful teams for the Yankees in the 1920s, he continued to make personnel changes in order to maintain his teams' superiority in the AL. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1964

Huggins was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, where his father, an Englishman, worked as a grocer.[1] His mother was a native of Cincinnati. He had two brothers and one sisterHuggins attended Woodward High School, Walnut Hills High School, and later the University of Cincinnati.,[2][3] where he studied law and played college baseball for the Cincinnati Bearcats baseball team. A shortstop, he was named team captain of the Bearcats in 1900.[2] Seeing him consumed with baseball, his law professors summoned him to justify why they should keep him in the law program.[3]

Huggins' father, a devout Methodist, objected to his son playing baseball on Sundays.[1] But Huggins played semi-professional baseball in 1898 for the Cincinnati Shamrocks, a team organized by Julius Fleischmann,[4] where he played under the pseudonym "Proctor" due to his father's opposition and his amateur status.[1][2] In 1900, he played for Fleischmann's semiprofessional team based in the Catskill Mountains, the Mountain Tourists, leading the team with a .400 batting average.[1][2]

After receiving his law degree from Cincinnati, Huggins realized that he could make even more money playing baseball,[1] and as such William Howard Taft, one of Huggins' law professors, advised him to play baseball.[4][5] He was admitted to the bar, but never practiced law.

Huggins fell ill on September 20, 1929, and checked into Saint Vincent's Catholic Medical Center for erysipelas. His condition was complicated by the development of influenza with high fever.[53][54] The Yankees' club physician, in consultation with other doctors, decided to administer blood transfusions.[53][55] But despite their best efforts, Huggins died at the age of 50 on September 25, 1929 of pyaemia.[53] The American League canceled its games for the following day out of respect,[56] and the viewing of his casket at Yankee Stadium drew thousands of tearful fans. A moment of silence was held for Huggins before the start of Game 4 of the 1929 World Series (at Philadelphia's Shibe Park, after which the A's overcame an 8-0 Cub advantage with 10 runs in the last of the seventh for a spectacular 10-8 come-from-behind victory and a 3-1 Series advantage).[57] He was interred in Spring Grove Cemetery in his native Cincinnati.[3]

The Yankees found it difficult to replace Huggins. Art Fletcher managed the team for its final eleven games of the 1929 season, but he did not want to manage the team full-time. After the season, Ruppert offered the job in turn to Fletcher, Donie Bush and Eddie Collins, all of whom declined. Eventually, "Bob the Gob" Shawkey agreed to serve as the Yankees manager for the 1930 season, leading the team to a third-place finish.[

In 1915, umpire and sportswriter Billy Evans, writing about the scarcity of competent second basemen in baseball, listed Huggins, Collins, Pratt, Johnny Evers, and Nap Lajoie as the best in the game.[5] He later wrote that Huggins was "one of the greatest managers I have ever met".[62] Bill James ranked Huggins as the 37th best second baseman of all time in 2001 in his The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.[56]

The Yankees dedicated a monument to Huggins on May 30, 1932, placing it in front of the flagpole in center field at Yankee Stadium. Huggins was the first of many Yankees legends granted this honor, which eventually became "Monument Park", dedicated in 1976. The monument calls Huggins "A splendid character who made priceless contributions to baseball."[63] The Yankees also named a field at Al Lang Stadium, their spring training home, after Huggins.[50][64]

Huggins was included on the ballot for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937, 1938, 1939, 1942, 1945, 1946, 1948, and 1950,[a] failing to receive the number of votes required for election on those occasions. The Veterans Committee elected Huggins to the Hall of Fame in February 1964,[25] and he was posthumously inducted that summer

Huggins was a private man who kept to himself. He lived in Cincinnati during the winters while playing for the Reds and Cardinals,[2] but began to make St. Petersburg, Florida his winter home while managing the Yankees.[66] Huggins did not marry,[2] and lived with his sister while in Cincinnati.[3]

Huggins invested in real estate holdings in Florida,[67] although he sold them in 1926 as they took too much of his time away from baseball.[68] He enjoyed playing golf and billiards in his spare time

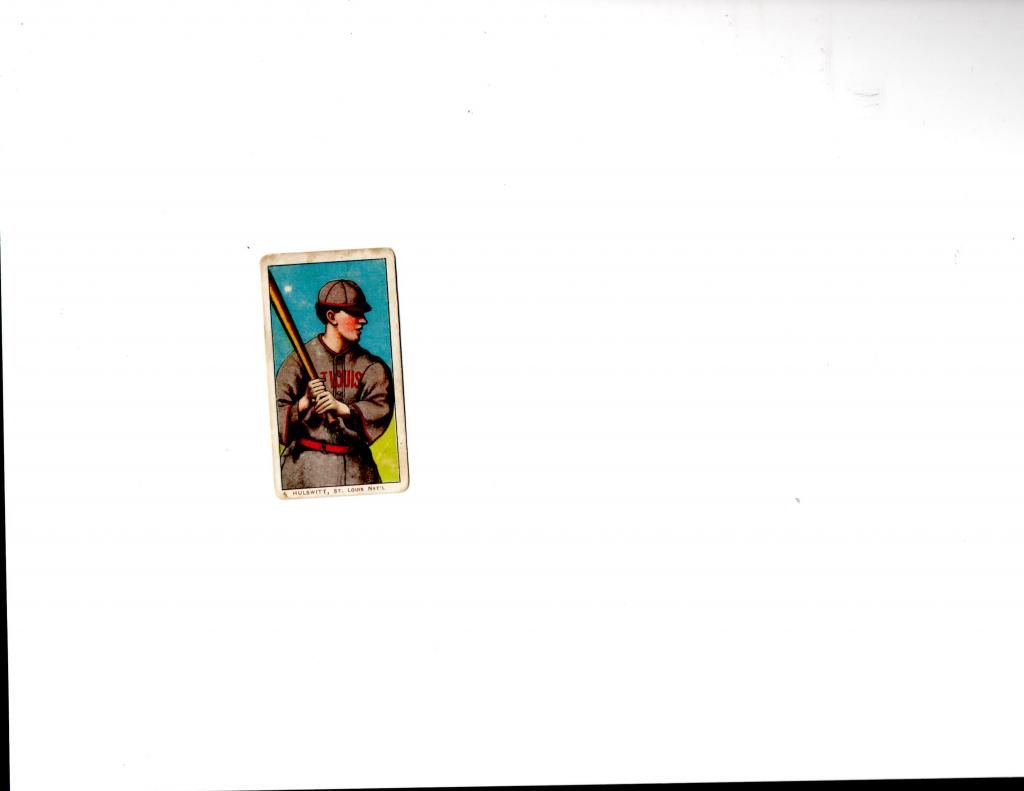

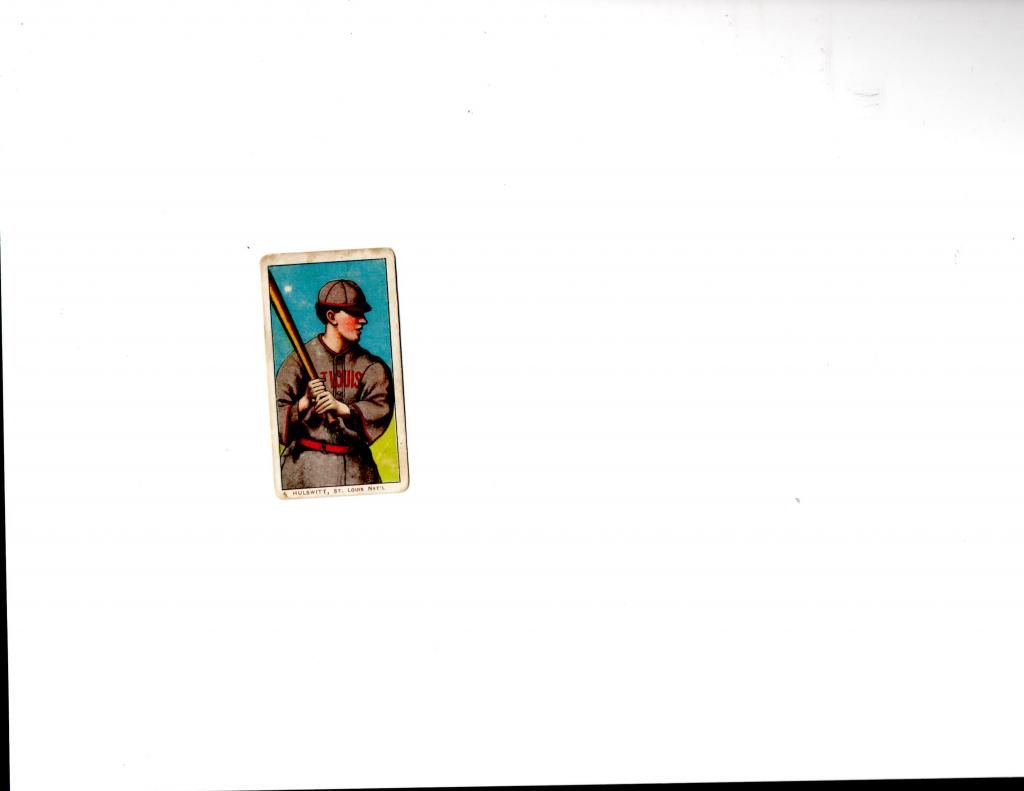

Rudy Hulswitt

Rudolph Edward Hulswitt (February 23, 1877 in Newport, Kentucky – January 16, 1950 in Louisville, Kentucky), was a professional baseball player who played shortstop in the Major Leagues from 1899-1910. He would play for the Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds, Louisville Colonels, and St. Louis Cardinals

![[Image: roughdraft_edited-1.jpg]](http://i51.photobucket.com/albums/f354/blayneroessler/roughdraft_edited-1.jpg)

Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-15-2015, 12:26 PM

(This post was last modified: 02-15-2015, 02:53 PM by waynetalger.)

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Hulswitt

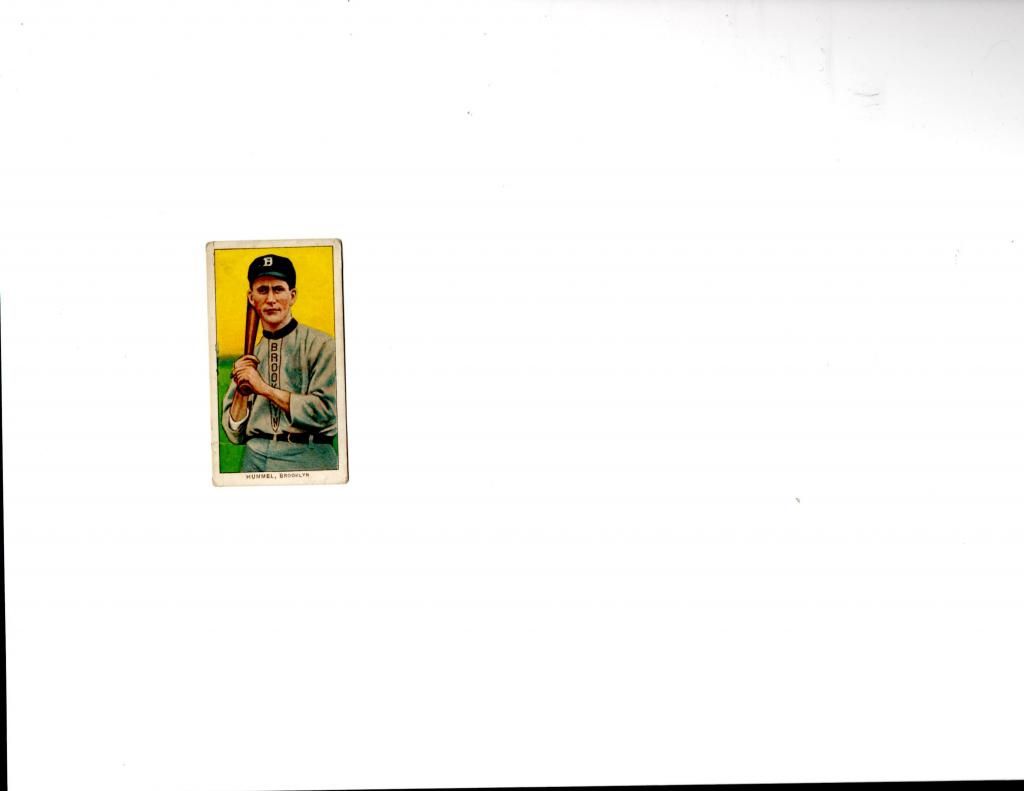

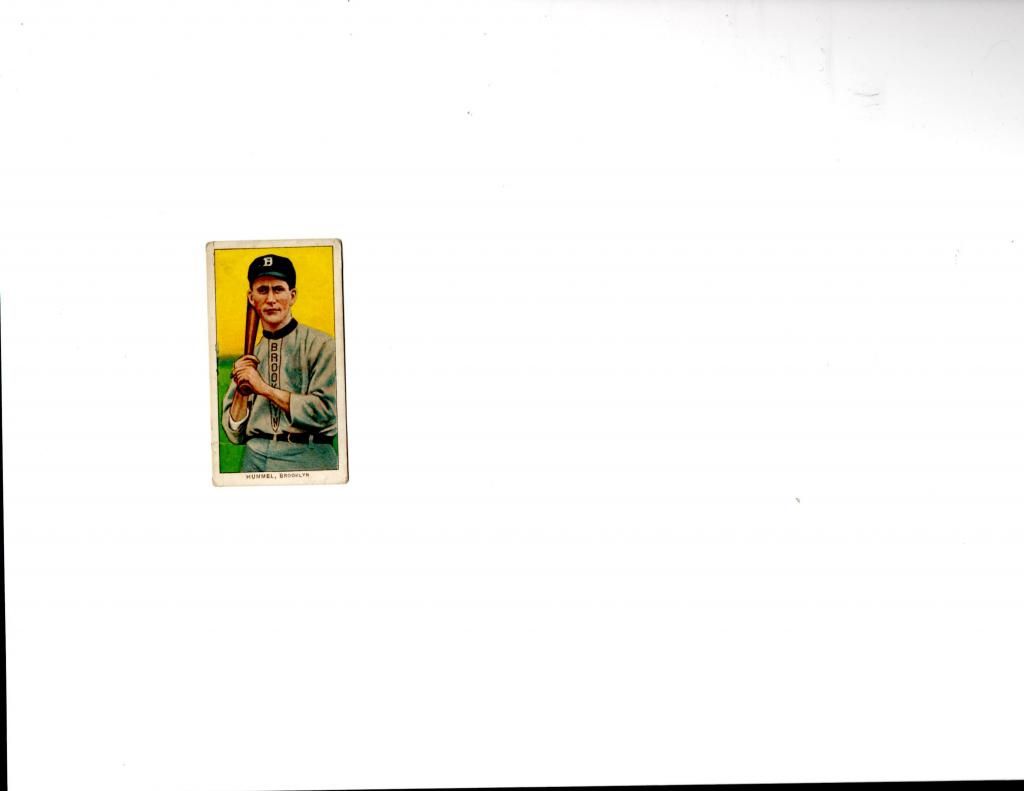

John Hummel

John Edwin Hummel (April 4, 1883 – May 18, 1959) born in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, was a Utility player for the Brooklyn Superbas/Brooklyn Dodgers/Brooklyn Robins (1905–15) and New York Yankees (1918). He attended college at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania.

He led the National League in strikeouts (81) in 1910.

He died in Springfield, Massachusetts at the age of 76.

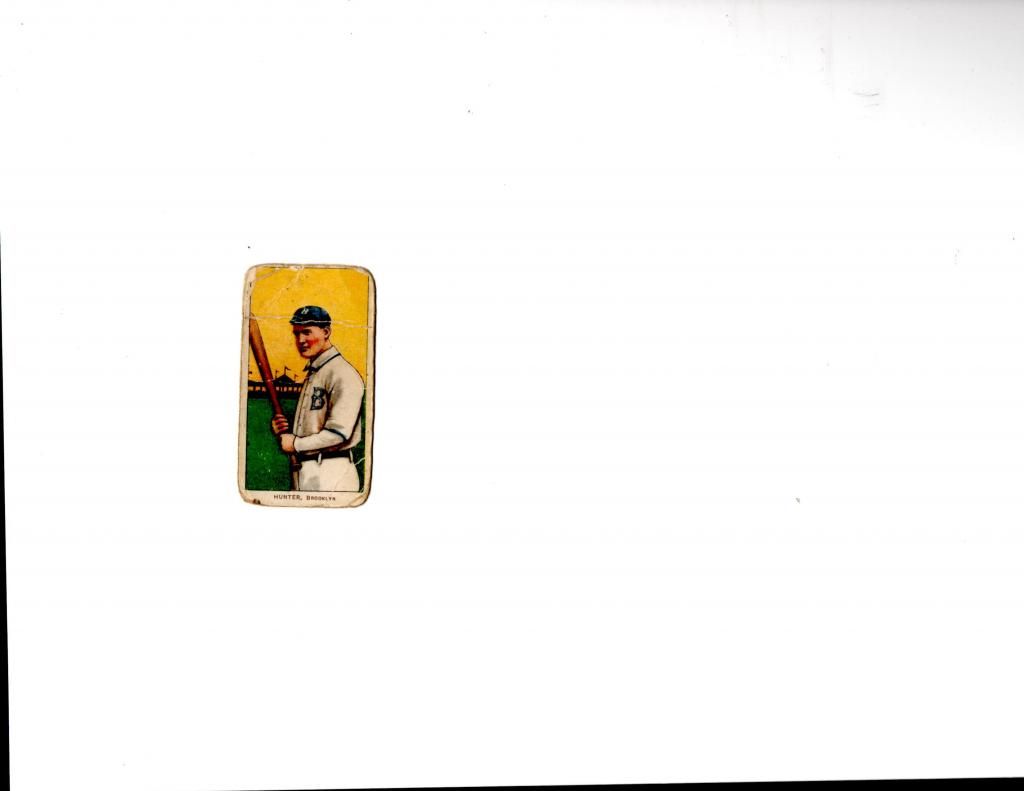

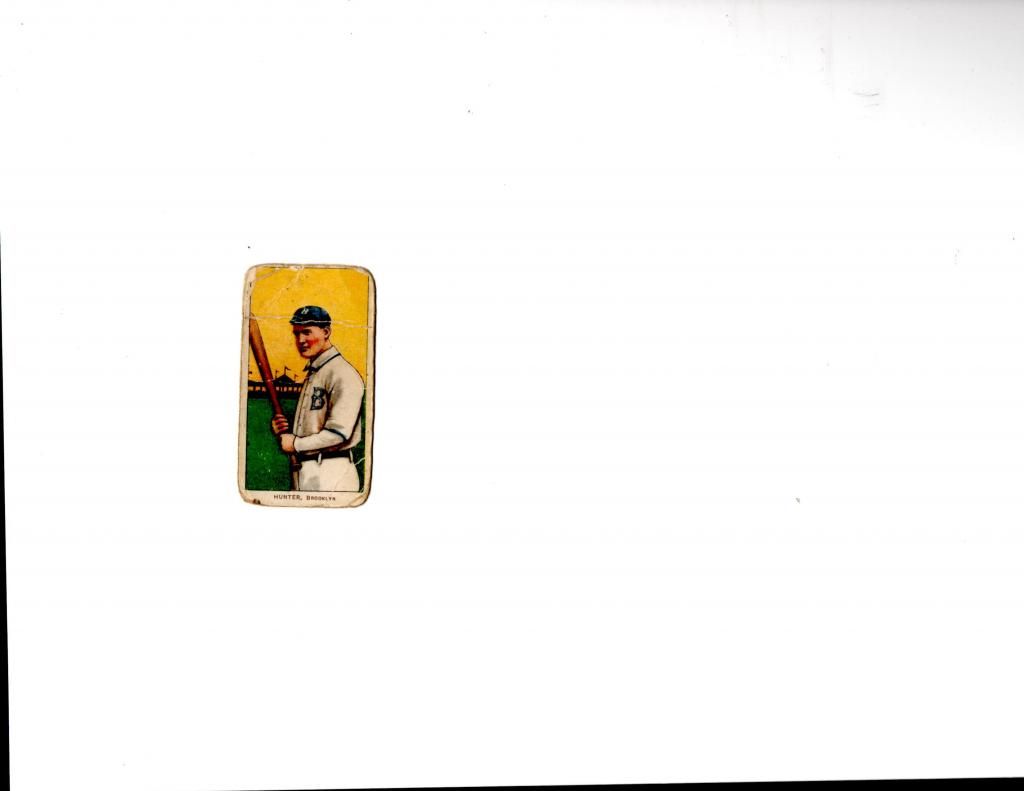

George Hunter

George Henry Hunter (July 8, 1887 in Buffalo, New York – January 11, 1968 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) was a pitcher and an outfielder in Major League Baseball. He played for the Brooklyn Superbas during the 1909 and 1910 baseball seasons. His brother Bill Hunter played for the Louisville Eclipse during the 1884 season

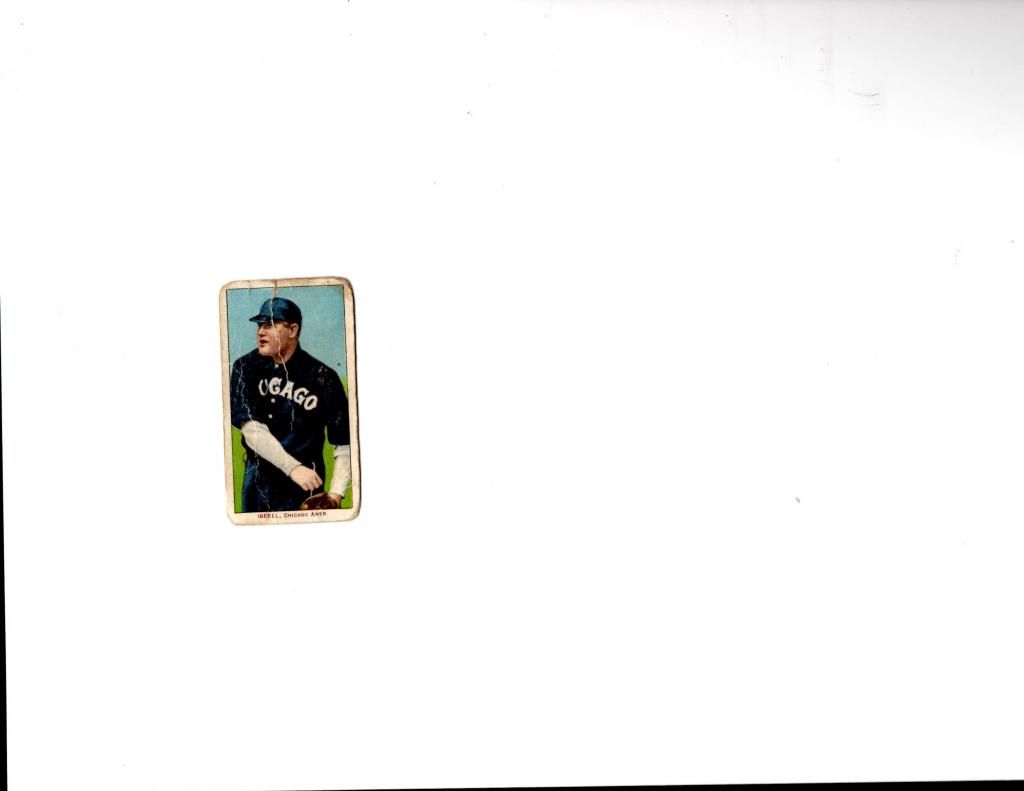

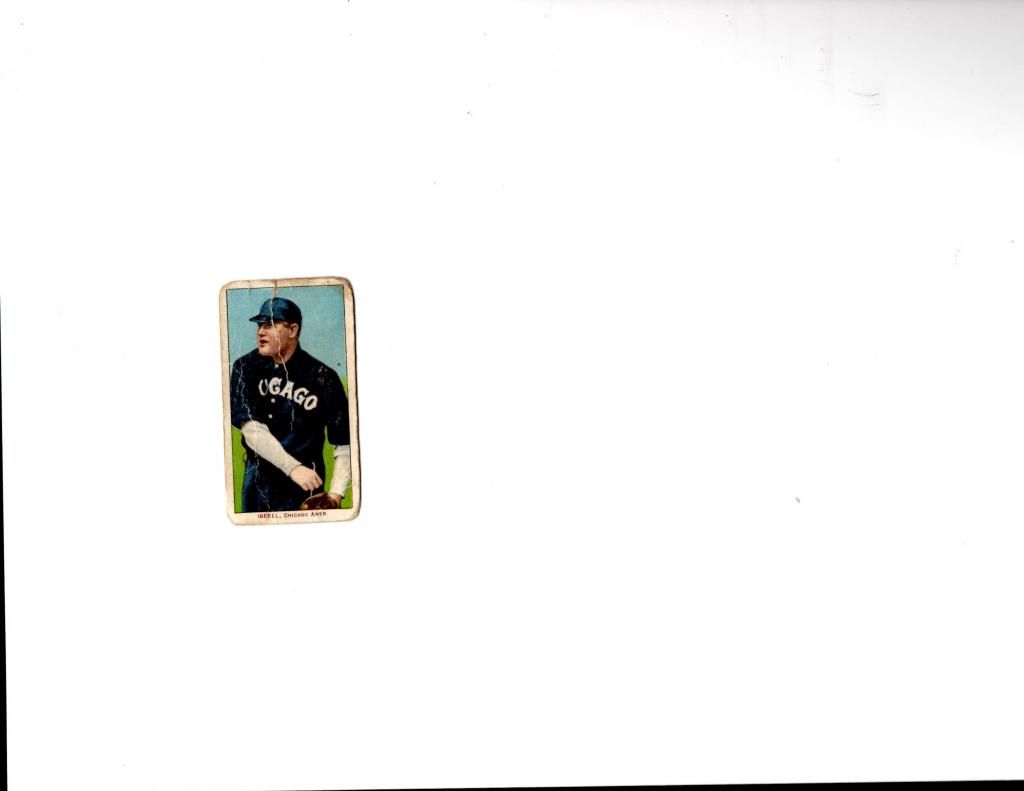

Frank Isbell

William Frank Isbell (August 21, 1875 – July 15, 1941) was a Major League first baseman, second baseman, and outfielder in the 1910s. He played for the Chicago Cubs in 1898 briefly, where he had 37 hits in 159 at bats (.233 batting average). With the Cubs, he pitched and played outfield more than anything else. Thirteen of his seventeen games pitched came with the Cubs. After not being seen in baseball for the next year, he showed up again in 1900 playing for the Chicago White Sox as a full-time first baseman. The American League was not recognized in the Majors until 1901. He played with them until 1909. He batted left-handed, but threw right-handed.

Born in Delevan, New York, Isbell was nicknamed Bald Eagle due to his receding hairline, something he was quite sensitive about. Isbell was a good enough hitter to earn a starting spot on some very good White Sox teams including the pennant-winning 1901 team, managed by Clark Griffith, the 2nd place 1905 team led by Fielder Jones, and finally the 1906 World Series champion White Sox that included shortstop George Davis and pitchers Doc White and Ed Walsh. That team was known as one of the worst hitting teams to ever win the World Series, with only Davis and Isbell hitting above .260 (Davis hit .277, Isbell .279). He also set many other offensive World Series records that year, including doubles and extra base hits in a game. However, Isbell was better known for his outstanding speed, even for that day-in-age. He never beat out his 1901 season when he had 52 stolen bases and led the Majors, but he averaged 37 steals a year and ended out with 253 in his career.

In a 10-year career and 1119 games, he ended out with a .250 batting average with 13 home runs and 455 RBIs. He had 1056 career hits in 4219 at bats. As a pitcher, he went 4–7 with a 3.59 ERA.

Isbell also became notable for being manager and owner of many teams in the Western League. He died in Wichita, Kansas.

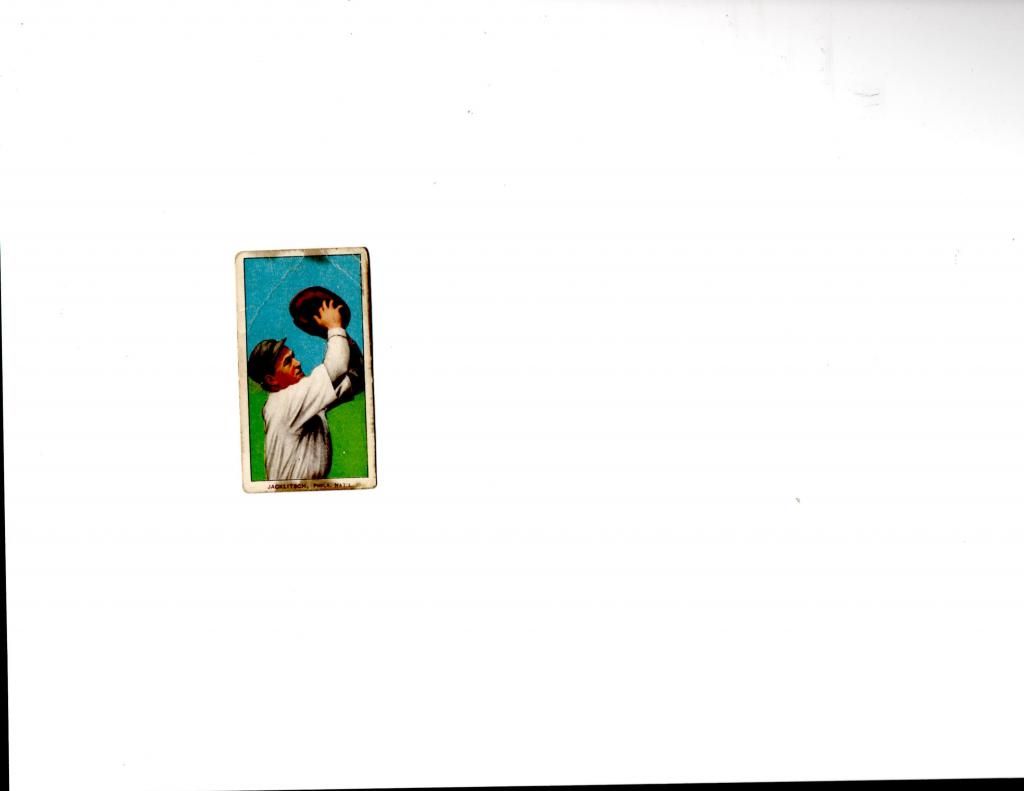

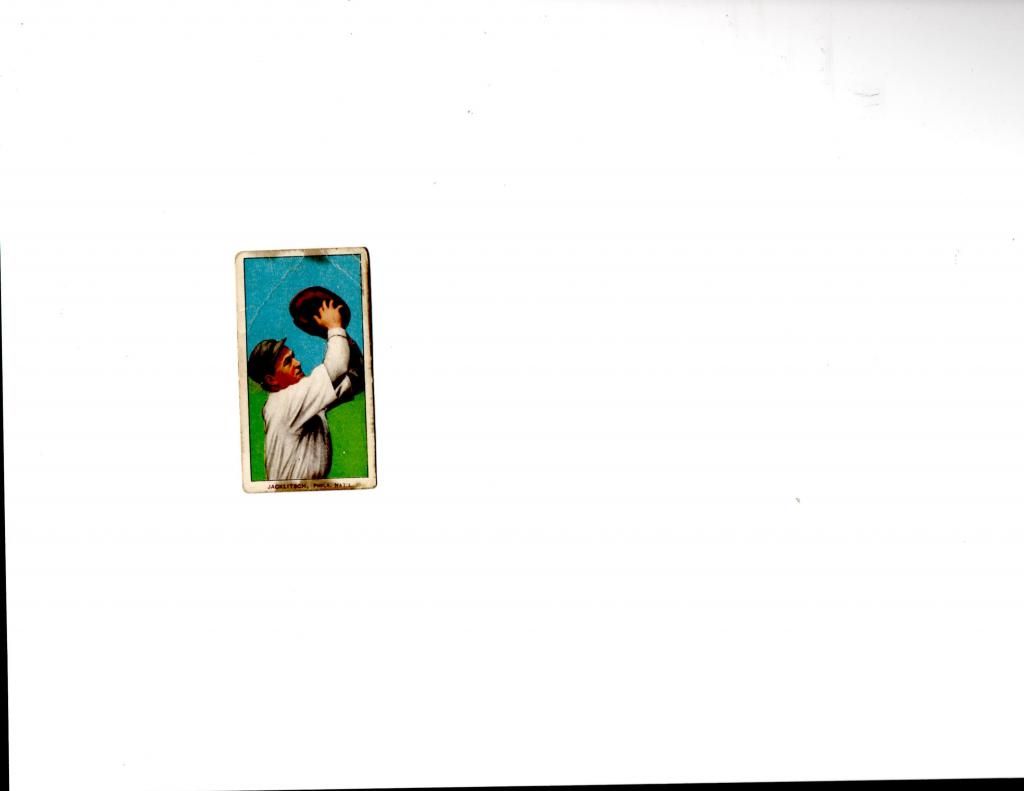

Fred Jacklitsch

Frederick Lawrence Jacklitsch (May 24, 1876 – July 18, 1937), was a professional baseball player. He played all or part of thirteen seasons in Major League Baseball between 1900 and 1917, primarily as a catcher

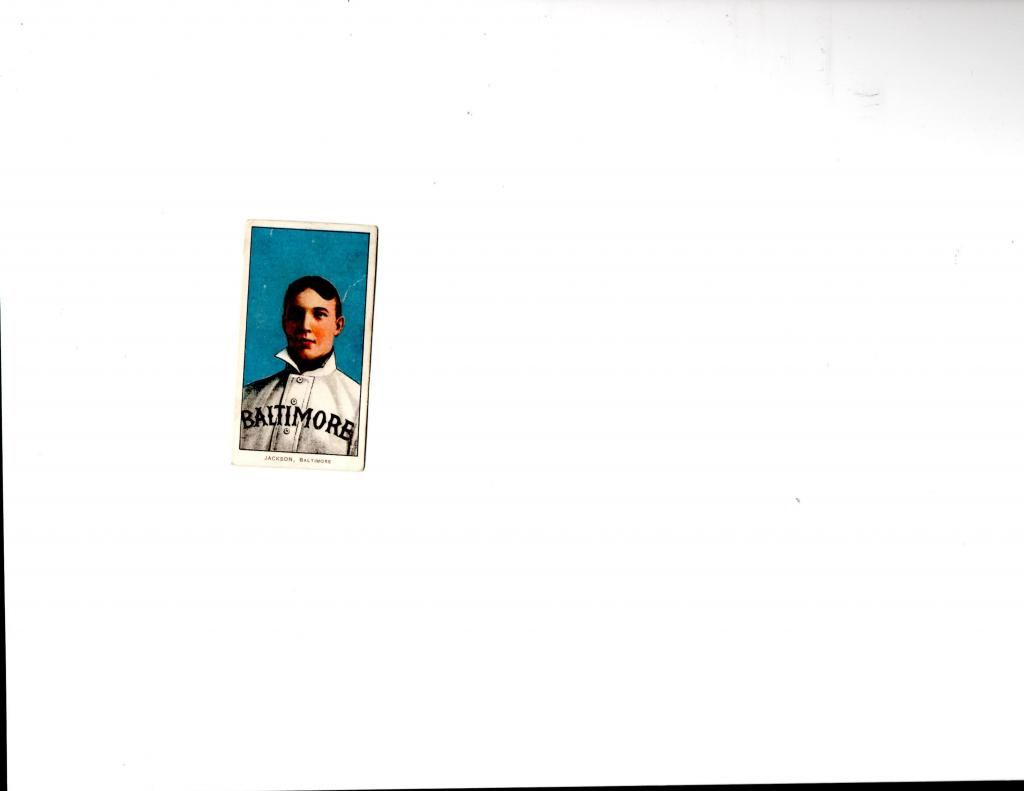

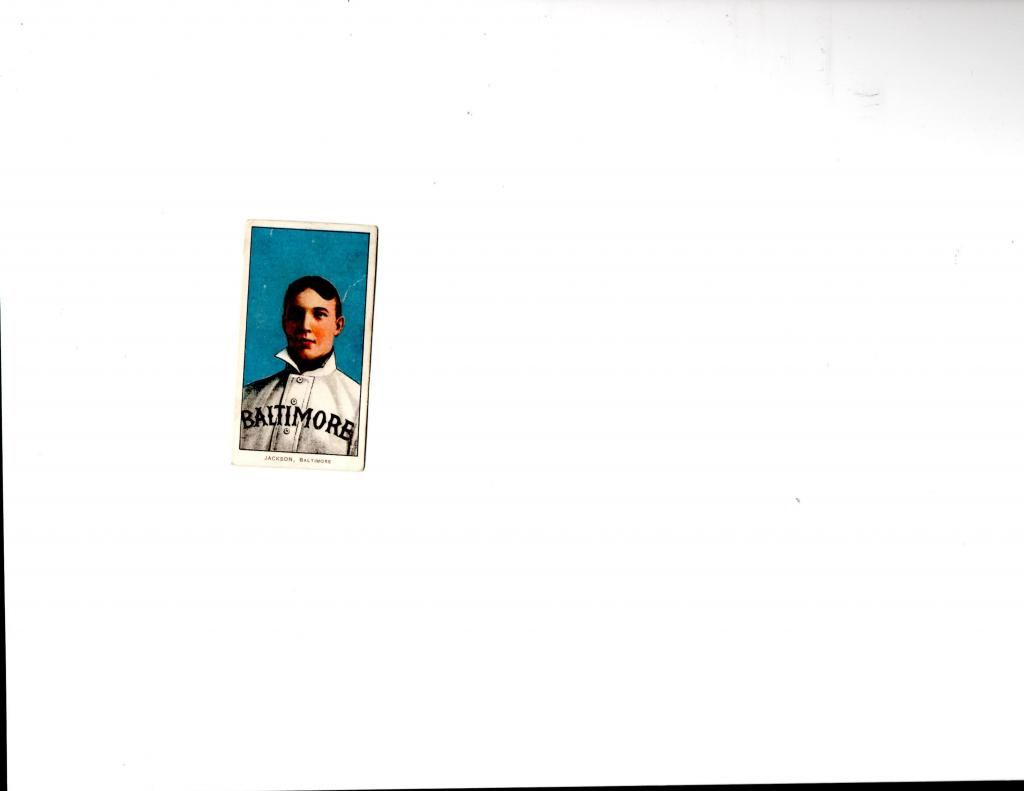

Jimmy Jackson

James Benner (Jim) Jackson (November 28, 1877 – October 9, 1955) was a Major League Baseball outfielder. Jackson played for the Baltimore Orioles, the New York Giants, and the Cleveland Naps in 1901 and 1902, and again from 1905 to 1906. In 348 career games, he had a .235 batting average with 300 hits in 1274 at-bats. He batted and threw right-handed.

He attended the University of Pennsylvania.

Jackson was born and died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hughie Jennings (accident Prone)

Hugh Ambrose Jennings (April 2, 1869 – February 1, 1928) was a Major League Baseball player and manager from 1891 to 1925. Jennings was a leader, both as a batter and as a shortstop, with the Baltimore Orioles teams that won National League championships in 1894, 1895, and 1896. During the three championship seasons, Jennings had 355 RBIs and hit .335, .386, and .401. Jennings was a fiery, hard-nosed player who was not afraid to be hit by a pitch to get on base. In 1896, he was hit by a pitch 51 times – a major league record that has never been broken. Jennings also holds the career record for being hit by a pitch with 287, with Craig Biggio (who retired in 2007) holding the modern-day career record of 285. Jennings also played on the Brooklyn Superbas teams that won National League pennants in 1899 and 1900. From 1907-1920, Jennings was the manager of the Detroit Tigers, where he was known for his colorful antics, hoots, whistles, and his famous shouts of "Ee-Yah" from the third base coaching box. Jennings suffered a nervous breakdown in 1925 that forced him to leave Major League Baseball. He died in 1928 and was posthumously inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

Born in Pittston, Pennsylvania, Jennings was the son of Irish immigrants, James and Nora, who according to Jack Smiles's biography of Jennings, Ee-yah : The Life and Times of Hughie Jennings, Baseball Hall of Famer (page 7 ), arrived in Pittston in 1851.

Jennings worked as a breaker boy (young boys who separated the coal from the slate) in the local anthracite coal mines. He drew attention playing shortstop for a semi-professional baseball team in Lehighton, Pennsylvania in 1890. He was signed by the Louisville Colonels of the American Association in 1891. He stayed with the Colonels when they joined the National League in 1892 and was traded on June 7, 1893 to the Baltimore Orioles.

Jennings' life was filled with several tragic accidents. There was the beaning incident in Philadelphia that left him unconscious for three days. While attending Cornell, he fractured his skull diving head-first into a swimming pool at night, only to find the pool had been emptied.[1] In December 1911, Jennings came close to death after an off-season automobile accident. While driving a car given to him by admirers, Jennings' car overturned while crossing a bridge over the Lehigh River near Gouldsboro, 23 miles southeast of Scranton. In the crash, Jennings again fractured his skull, suffered a concussion of the brain, and broke both legs and his left arm. For several days after the accident, doctors were unsure if Jennings would survive.[3]

The physical abuse and blows to the head undoubtedly took their toll. During the 1925 season, McGraw was ill, and Jennings was put in full charge of the Giants. The team finished in second place and the strain caught up with Jennings, who suffered a nervous breakdown when the season ended.[3] According to his obituary, Jennings "was unable to report" to spring training in 1926 due to his condition. Jennings retired to the Winyah Sanatorium in Asheville, North Carolina. He did return home to Scranton, Pennsylvania, spending much of his time recuperating in the Pocono Mountains.[3] In early 1928, Jennings died from meningitis in Scranton, Pennsylvania at age 58.

Jennings was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945 as a player

Davvy Jones (pharmacist also on the play where 1rst base was stolen )

Born in Cambria, Wisconsin, as David Jefferson, he later changed his last name to Jones. He attended college at Northern Illinois University, and learned to be a druggist before becoming a ball player while living in Portage and Mauston, Wisconsin. Jones would go on to purchase a drug store in Detroit in 1910 during his playing days.[2]

Jones was 21 years old when he broke into the big leagues on September 15, 1901, with the Milwaukee Brewers.

Jones is also known for recounting a famous story in The Glory of Their Times about the early ballplayer/comedian Germany Schaefer. According to Jones, Schaefer was the only player who ever stole first base in a ballgame. The instance evidently took place September 4, 1908 during a Detroit game versus Cleveland. With Davy Jones on third and Schaefer at first, the double steal was on. But as Germany slid into second base safe, the Cleveland catcher held onto the ball. In order to set up the double-steal again, Schaefer took off screaming for first on the next pitch and dove in headfirst in without a play. This stunned the players, fans and umpires, but it was perfectly legal. On the next pitch, the double steal worked. In the same interview, Jones also mentions how, as the lead off batter for the Detroit Tigers, he was the first hitter to face the great pitcher Walter Johnson.

At the age of 38, having retired from baseball and running a successful pharmacy in Detroit, Jones was inserted into one game by an old friend who was managing the ball club, Hughie Jennings. Jones attended the final game of the season as a spectator, and since the contest had no bearing on the pennant race, he and a coach were used in the game. The baseball used in that game is in the National Baseball Hall of Fame collection and is inscribed: "Last ball used in game at Navin Field in last game of season, 1918, caught by Davy Jones. Hit by Shano Collins of the Chicago White Sox. Season ending on Labor Day on account of War." The circumstances of the play in which the ball was involved went unrecognized in the official statistical record for more than 85 years

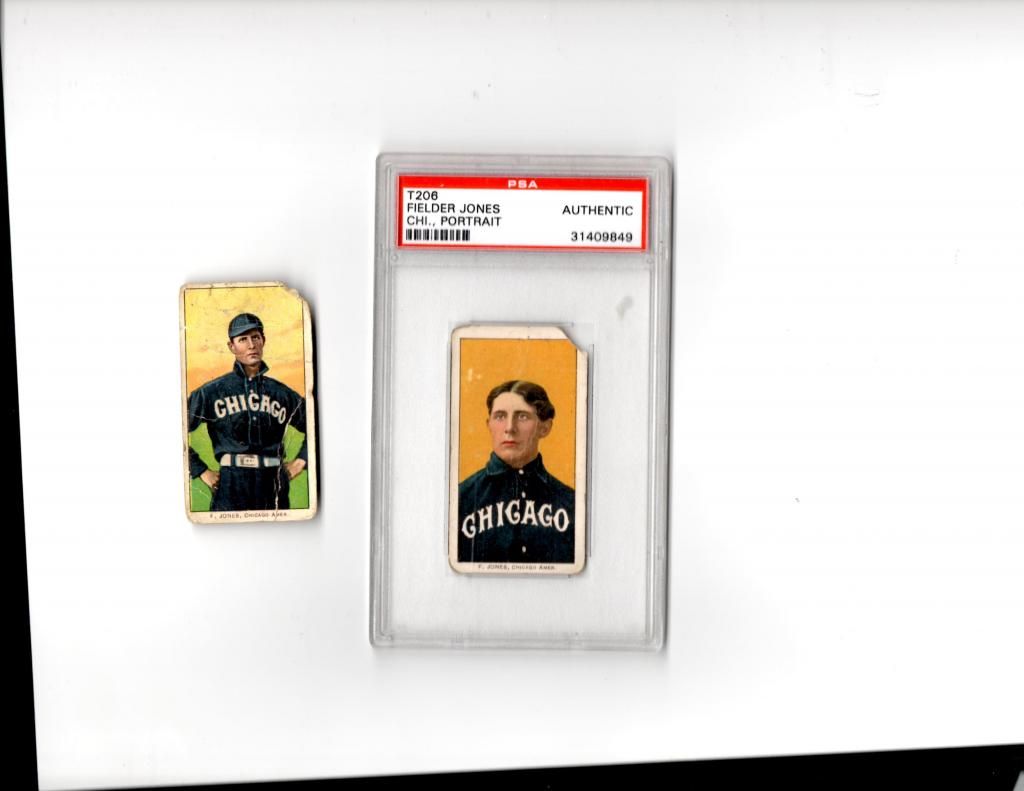

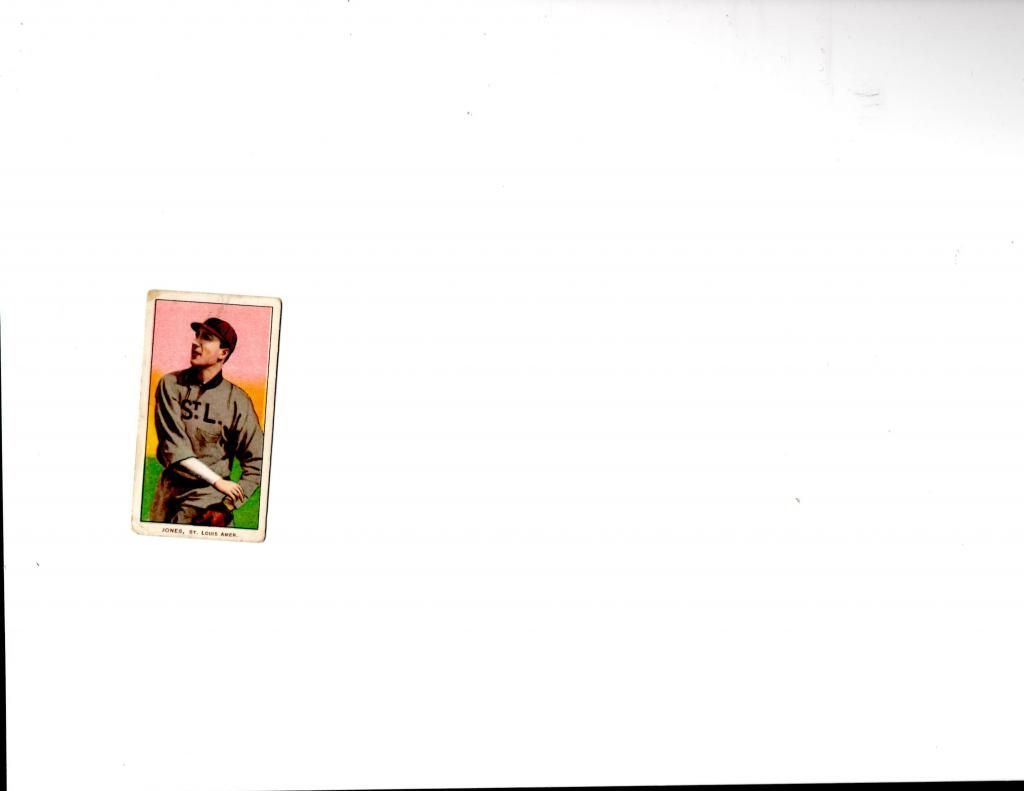

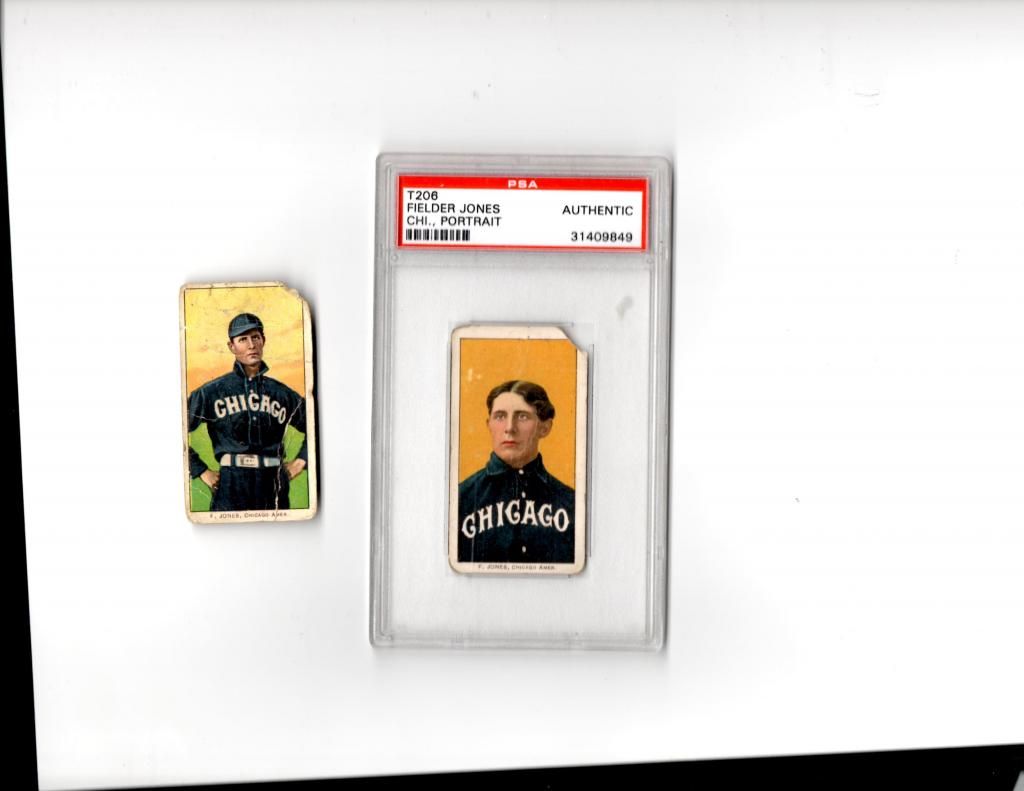

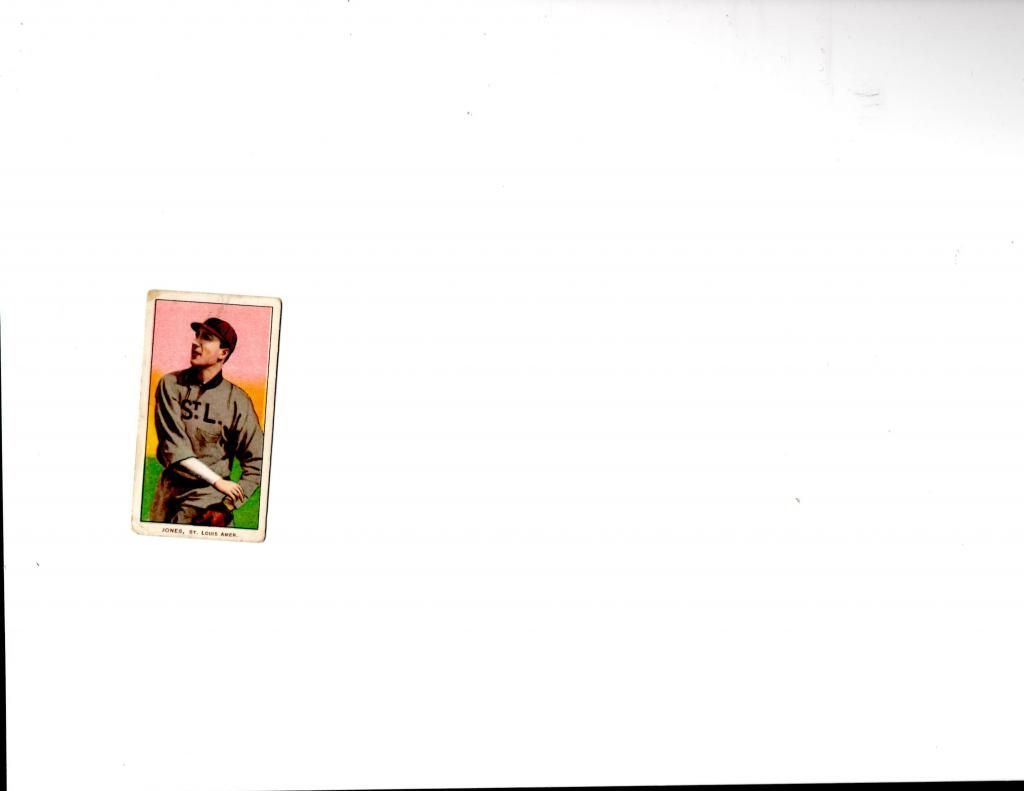

Fielder Jones

Fielder Allison Jones (August 13, 1871 – March 13, 1934) was an American center fielder and manager in baseball. Born in Shinglehouse, Pennsylvania, his playing career began with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms/Superbas in 1896. In 1901, he joined the Chicago White Stockings in the new American League, where he would finish his playing career. Six years after his last game with the White Sox, he joined the St. Louis Terriers of the newly formed Federal League, where he served as a player-manager before the league folded.

Jones managed the "Hitless Wonders" in the 1906 World Series, which was the White Sox' first World Series win. That year, the White Sox had a team batting average of only .230.[1]

He had one last stint as a manager with the St. Louis Browns, but his earlier success with the White Sox eluded him, as his St. Louis teams never finished above fifth place.

He was head coach for the Oregon State Beavers baseball team in 1910, going 13-4-1 and winning the Northwest championship.[2]

He died in Portland, Oregon at age 62

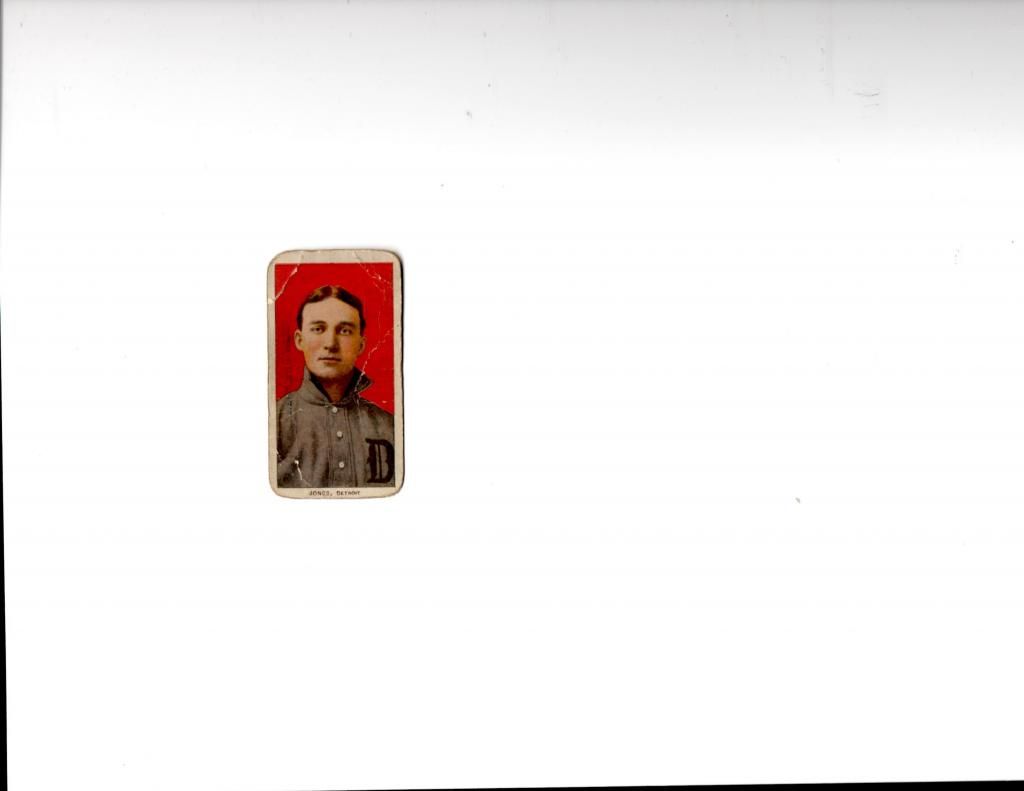

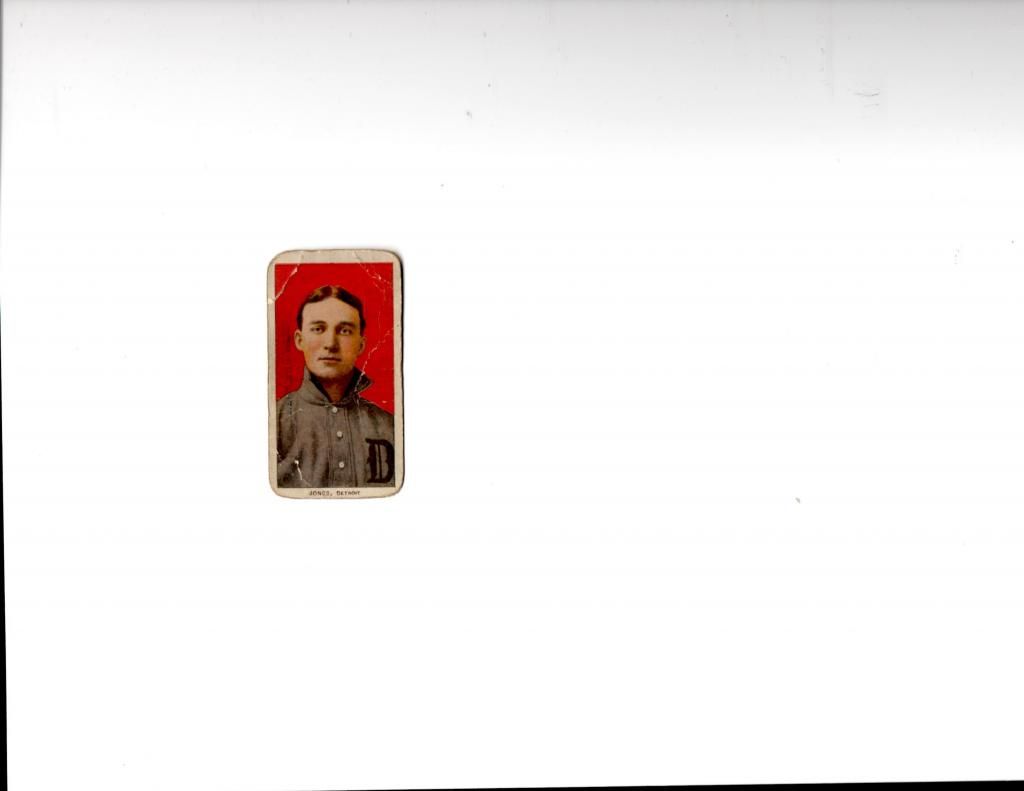

Tom Jones

Thomas Jones (January 22, 1877 – June 19, 1923) was an American first baseman in Major League Baseball. He played eight seasons in the American League with the Baltimore Orioles (1902), St. Louis Browns (1904–09), and Detroit Tigers (1909–10). Born in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, he batted and threw right-handed.

He made his debut on August 25, 1902 with the Baltimore Orioles. With the Browns in 1906, he led the American League in sacrifices (40). In 1908, Jones led the AL in putouts (1,616) and double plays (79). During the 1909 season, he was traded to the Tigers from the Browns for Claude Rossman and played in the 1909 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1,058 career games, Jones batted .251 with 964 hits and 135 stolen bases.

Jones died in Danville, Pennsylvania, at age 46.

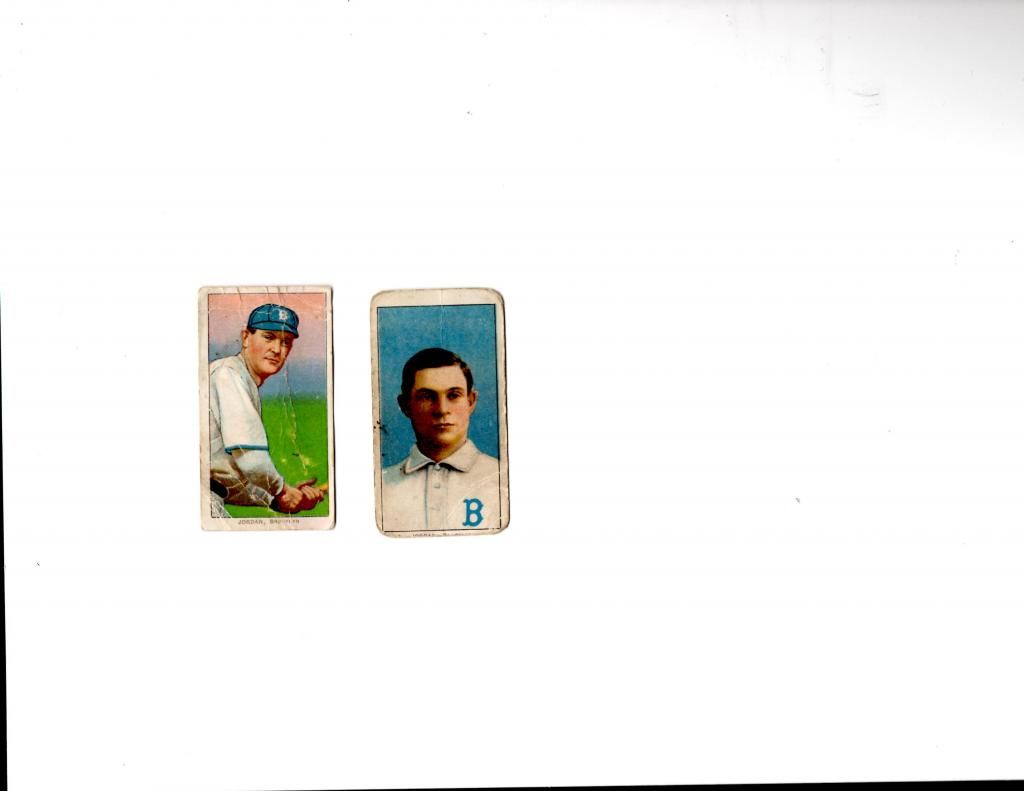

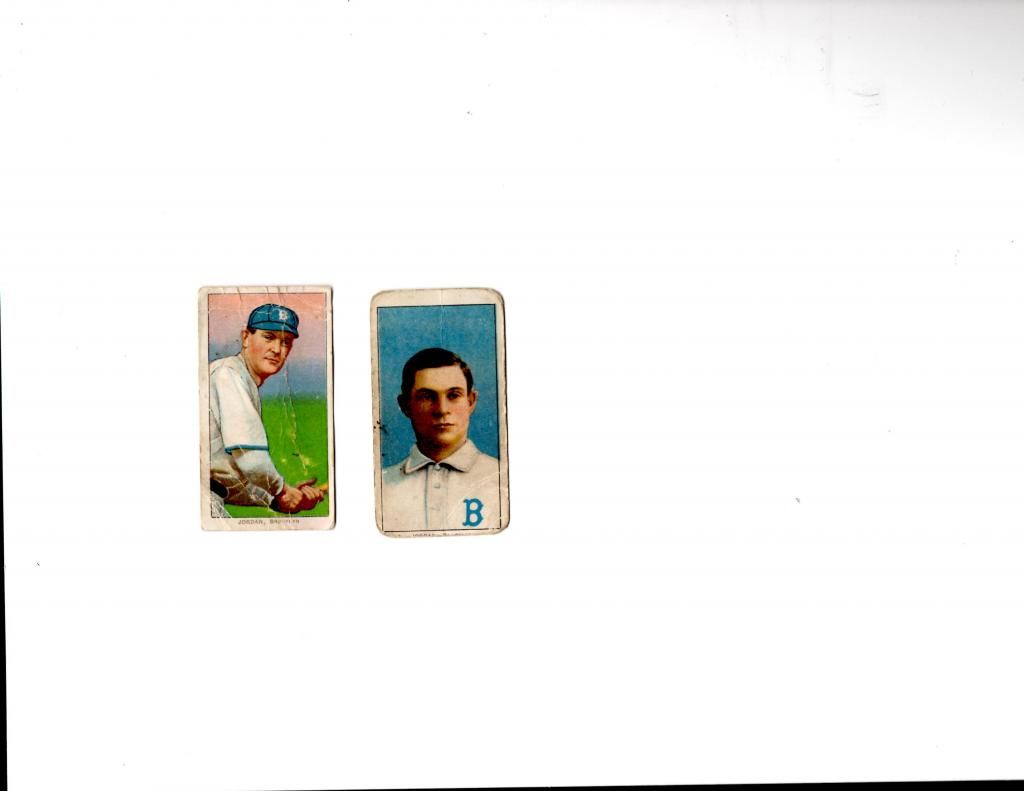

Tim Jordan

Timothy Joseph Jordan (February 14, 1879 – September 13, 1949) was a professional baseball player. He was a first baseman over parts of seven seasons with the Washington Senators, New York Highlanders and Brooklyn Supurbas. He led the National League in home runs twice, in 1906 and 1908 with Brooklyn. He was born and later died at the age of 70 in New York City.

![[Image: roughdraft_edited-1.jpg]](http://i51.photobucket.com/albums/f354/blayneroessler/roughdraft_edited-1.jpg)

Posts: 7,606

Threads: 512

Joined: Nov 2011

02-15-2015, 10:49 PM

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Tim Jordan

This thread is the most fun thread since I've been a member of the Forum!

Thanks, Wayne, for all this amazing information. Stuff like this keeps the memories of your Dad alive.

![[Image: Ch4Mt.png]](http://i.imgur.com/Ch4Mt.png)

I guess if I saved used tinfoil and used tea bags instead of old comic books and old baseball cards, the difference between a crazed hoarder and a savvy collector is in that inherent value.

Posts: 6,047

Threads: 182

Joined: Apr 2009

02-16-2015, 07:00 PM

(This post was last modified: 02-16-2015, 11:08 PM by waynetalger.)

RE: the famous 1909-11 T-206 with stories and scans Abbaticchio to Tim Jordan

Thank you Mitch, I wish he was still around to tell me some of the stories his Dad told him. I have forgotten much of the WW1 that he served in other than a Mule Skinner. I did promise him I would finish the set some day now I am back to working on that promise.

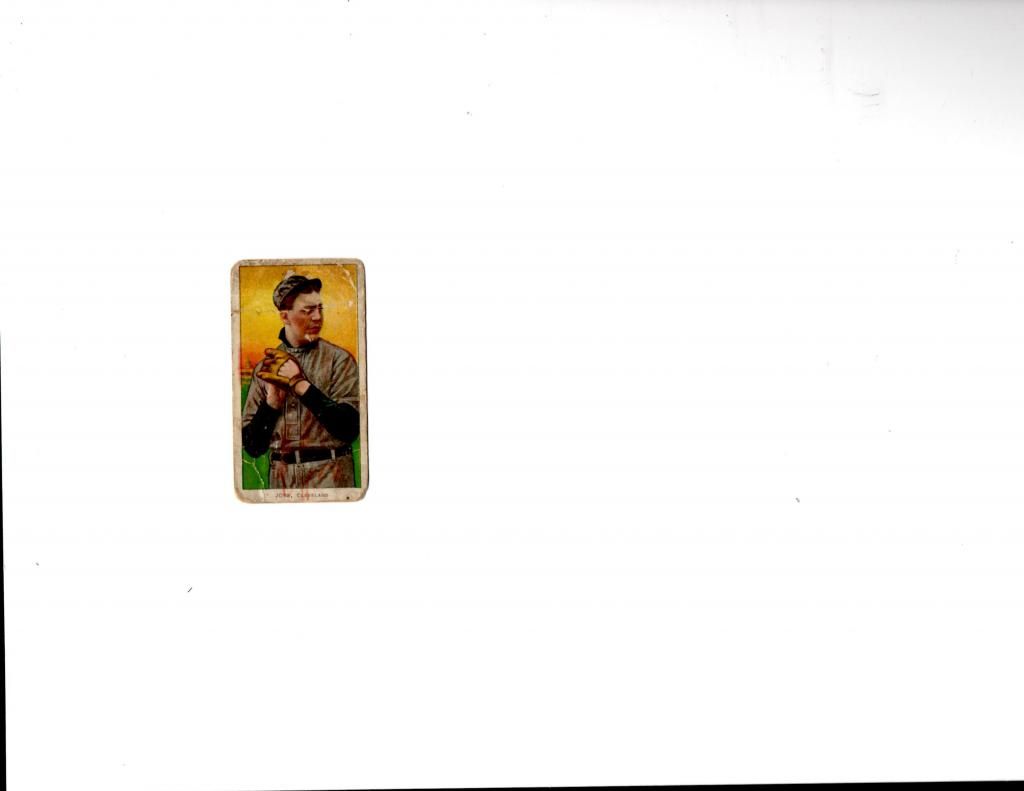

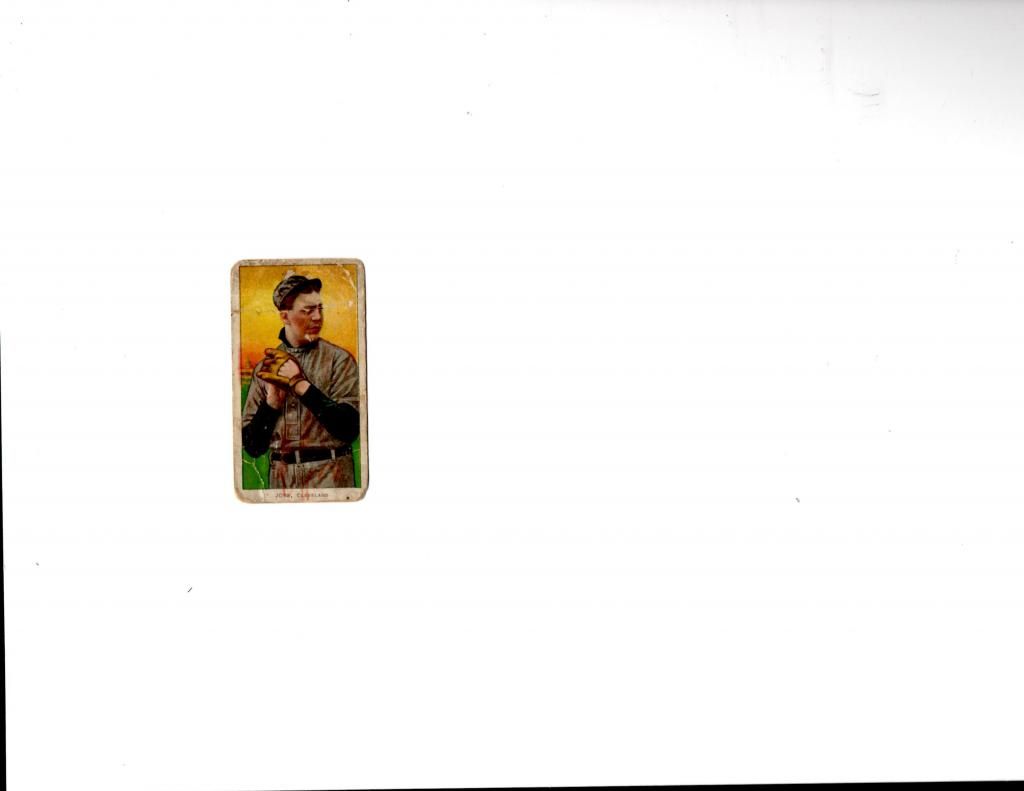

Addie Joss ( Next time you watch an allstar game think of Addie Joss)

Adrian "Addie" Joss (April 12, 1880 – April 14, 1911), nicknamed "The Human Hairpin,"[1] was an American pitcher in Major League Baseball (MLB). He pitched for the Cleveland Bronchos, later known as the Naps, between 1902 and 1910. Joss, who was 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) and weighed 185 pounds (84 kg), pitched the fourth perfect game in baseball history. His 1.89 career earned run average (ERA) is the second-lowest in MLB history.

Joss was born and raised in Wisconsin, where he attended St. Mary's College and the University of Wisconsin. He played baseball at St. Mary's and then played in a semipro league where he caught the attention of Connie Mack. Joss did not sign with Mack's team, but he attracted further major league interest after winning 19 games in 1900 for the Toledo Mud Hens. Joss had another strong season for Toledo in 1901.

After an offseason contract dispute between Joss, Toledo and Cleveland, he debuted with the Cleveland club in April 1902. Joss led the league in shutouts that year. By 1905, Joss had completed the first of his four consecutive 20-win seasons. Off the field, Joss worked as a newspaper sportswriter from 1906 until his death. In 1908, he pitched a perfect game during a tight pennant race that saw Cleveland finish a half-game out of first place; it was the closest that Joss came to a World Series berth. The 1910 season was his last, and Joss missed most of the year due to injury.

In April 1911, Joss became ill and he died the same month due to tuberculous meningitis. He finished his career with 160 wins, 234 complete games, 45 shutouts and 920 strikeouts. Though Joss played only nine seasons and missed significant playing time due to various ailments, the National Baseball Hall of Fame's Board of Directors passed a special resolution for Joss in 1977 which waived the typical ten-year minimum playing career for Hall of Fame eligibility.[2] He was voted into the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1978.

Addie Joss was born in Woodland, Dodge County, Wisconsin. His parents Jacob and Theresa (née Staudenmeyer) worked as farmers; his father, a cheesemaker who was involved in local politics, had emigrated from Switzerland.[5] A heavy drinker of alcohol, he died from liver complications in 1890, when Joss was 10 years old; Joss remained sober throughout his life as a result of his father's death.Joss attended elementary school in Juneau and Portage and high school at Wayland Academy in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. By age 16 he finished high school and began teaching himself. He was offered a scholarship to attend St. Mary's College (also known as Sacred Heart College) in Watertown, where he played on the school's baseball team.He also attended the University of Wisconsin (now University of Wisconsin-Madison), where he studied engineering. Officials in Watertown were impressed with the quality of play of St. Mary's and put the team on a semipro circuit.During his time on the semipro circuit, Joss employed his unique pitching windup, which involved hiding the ball until the very last moment in his delivery.

Connie Mack also sent a scout to watch Joss and later offered the young pitcher a job playing on his Albany club in the Western League, which Joss declined. In 1899, Joss played for a team in Oshkosh, earning $10 per week ($283 in today's dollars). After player salaries were frozen by team owners, Joss joined the junior team in Manitowoc, which had been split into two teams, as a second baseman and was soon promoted to the senior squad, where he was developed into a pitcher.[9] He was seen by a scout for the Toledo Mud Hens and in 1900 accepted a position with the team for $75 per month ($2,126). While in Ohio he was considered "the best amateur pitcher in the state."[10] He started the Mud Hens' season opener on April 28 and earned the win in the team's 16–8 victory He won 19 games for the club in 1900.

Before the 1908 season started, the Naps' home field, League Park, was expanded by about 4,000 seats. The Detroit Tigers, Chicago White Sox, and Naps were engaged in a race for the post-season described as "one of the closest and most exciting known.Three games remained in the regular season and the Naps were a half-game behind the Detroit Tigers as they headed into a October 2, 1908, match-up against the Chicago White Sox, who trailed the Naps by one game. Game attendance was announced at 10,598, which was labeled by sportswriter Franklin Lewis as an "excellent turnout for a weekday.The Naps faced future Hall of Fame pitcher Ed Walsh and recorded four hits; they were struck out by Walsh 15 times. The Naps' Joe Birmingham scored the team's only run, which came in the third inning. The tension in the ballpark was described by one writer as "a mouse working his way along the grandstand floor would have sounded like a shovel scraping over concrete."[9] In the ninth inning, Joss retired the first two batters then faced pinch hitter John Anderson. Anderson hit a line drive that would have resulted in a double had it not gone foul. He then hit a ball to Naps third baseman Bill Bradley which Bradley bobbled before throwing to first baseman George Stovall. Stovall dug the ball out of the ground to preserve the Naps' 1–0 lead. With the win, Joss recorded a perfect game, the second in American League history. He accomplished the feat with just 74 pitches, the lowest known pitch count ever achieved in a perfect game. Fans swarmed the field. After the game, Joss said, "I never could have done it without Larry Lajoie's and Stovall's fielding and without Birmingham's base running. Walsh was marvelous with his splitter, and we needed two lucky strikes to win.

For the season, Joss averaged 0.83 walks per nine innings, becoming one of 29 pitchers in MLB history to average less than one walk per nine innings.His season-ending WHIP of .806 is the fifth-lowest single-season mark in MLB history.[18] The Naps finished with a 90–64 record, a half-game behind Detroit. It was the closest Joss ever got to a World Series appearance

Joss attended spring training with Cleveland before the start of the 1911 season. He collapsed on the field from heat prostration on April 3 in an exhibition game in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He was taken to a local hospital and released the next day.As early as April 7, press reports had taken note of his ill health, but speculated about "ptomaine poisoning" or "nervous indigestion. The Naps traveled to Toledo for exhibition games on April 10 and Joss went to his home on Fulton Street where he was seen by his personal physician, Dr. George W. Chapman. Chapman thought Joss could be suffering from nervous indigestion or food poisoning. By April 9, as Joss was coughing more and had a severe headache, Chapman changed his diagnosis to pleurisy and reported that Joss would not be able to play for one month and would need ten days of rest to recover. Joss could not stand on his own and his speech was slurred. On April 13, Chapman sought a second opinion from the Naps' team doctor, who performed a lumbar puncture and diagnosed Joss with tuberculous meningitis.[b] The disease had spread to Joss' brain and he died on April 14, 1911 at age 31.

Joss was well-liked by his peers and baseball fans. Upon hearing of his death, the Press wrote "every train brings flowers" and "floral tributes by the wagonload are hourly arriving at the Joss home from all sections of the country. His family arranged for the funeral to take place on April 17. On that day, the Naps were to face the Detroit Tigers in the Tigers' home opener. Naps players signed a petition stating that they would not attend the game so they could instead attend the funeral. They asked for the game to be rescheduled, but the Tigers balked at the request. American League president Ban Johnson initially supported the Tigers' position, but he ultimately sided with the Naps. Naps owner Charles Somers and 15 Naps players attended the funeral, which was officiated by player-turned-evangelist Billy Sunday.

The first "all-star" game was played as a benefit for Joss's family on July 24, 1911. The Naps invited players from the other seven American League teams to play against them. Visiting club players who were involved in the game included Home Run Baker, Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Sam Crawford, Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, Gabby Street, and Smokey Joe Wood. "I'll do anything they want for Addie Joss' family," Johnson said.Washington Senators manager Jimmy McAleer volunteered to manage the all-stars. "The memory of Addie Joss is sacred to everyone with whom he ever came in contact. The man never wore a uniform who was a greater credit to the sport than he," McAleer said.The game was attended by approximately 15,270 fans and raised nearly $13,000 ($329,039) to help Joss' family members pay remaining medical bills.The Naps lost 5–3.

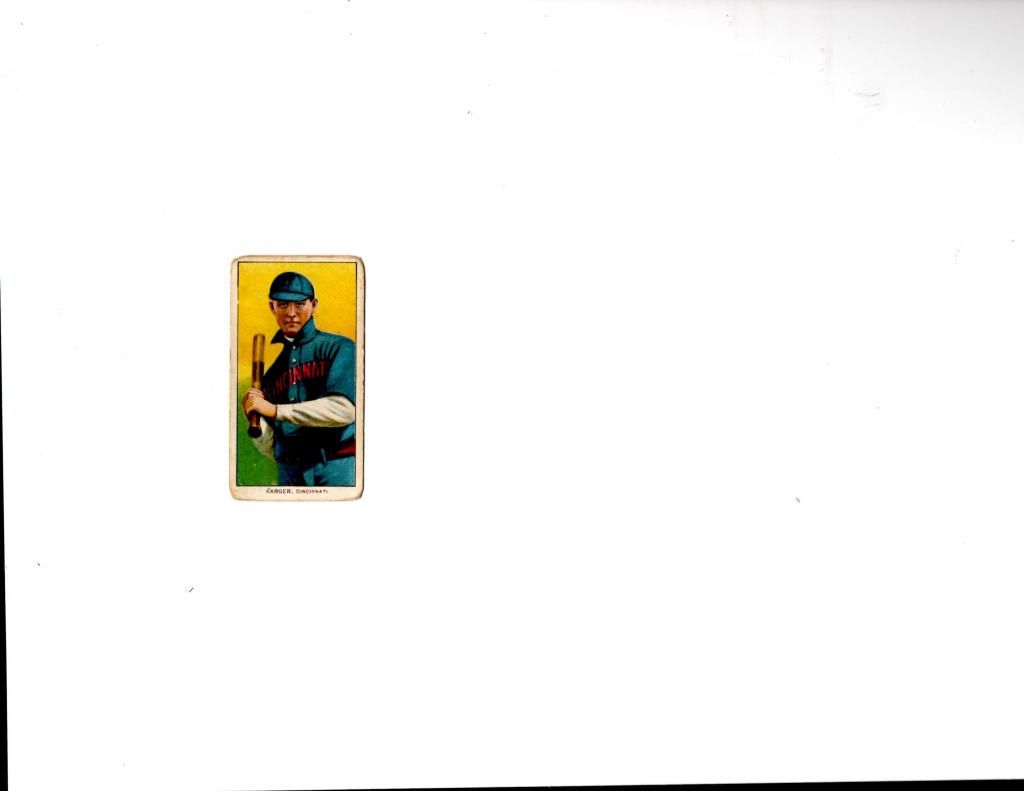

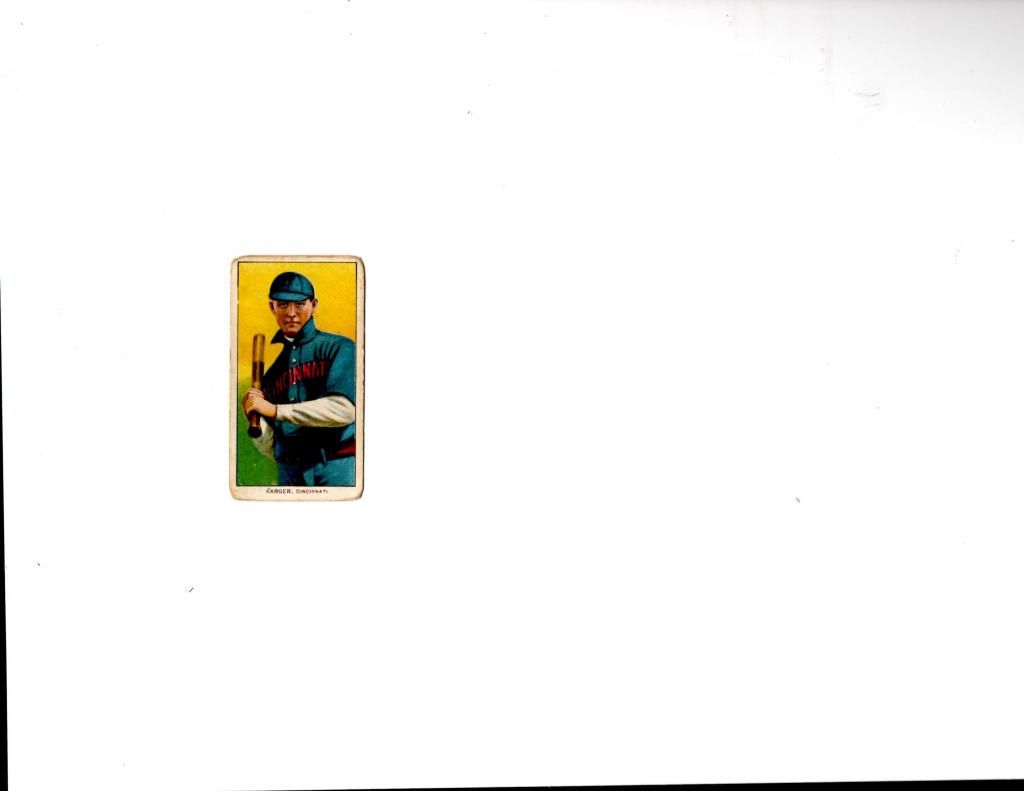

Ed Karger