NFL rushing legends Barry Sanders and Emmitt Smith are still going strong

By Dan Good | Contributing Editor

BALTIMORE – All these years later, and the reluctant superstar and the eager superstar remain grouped together.

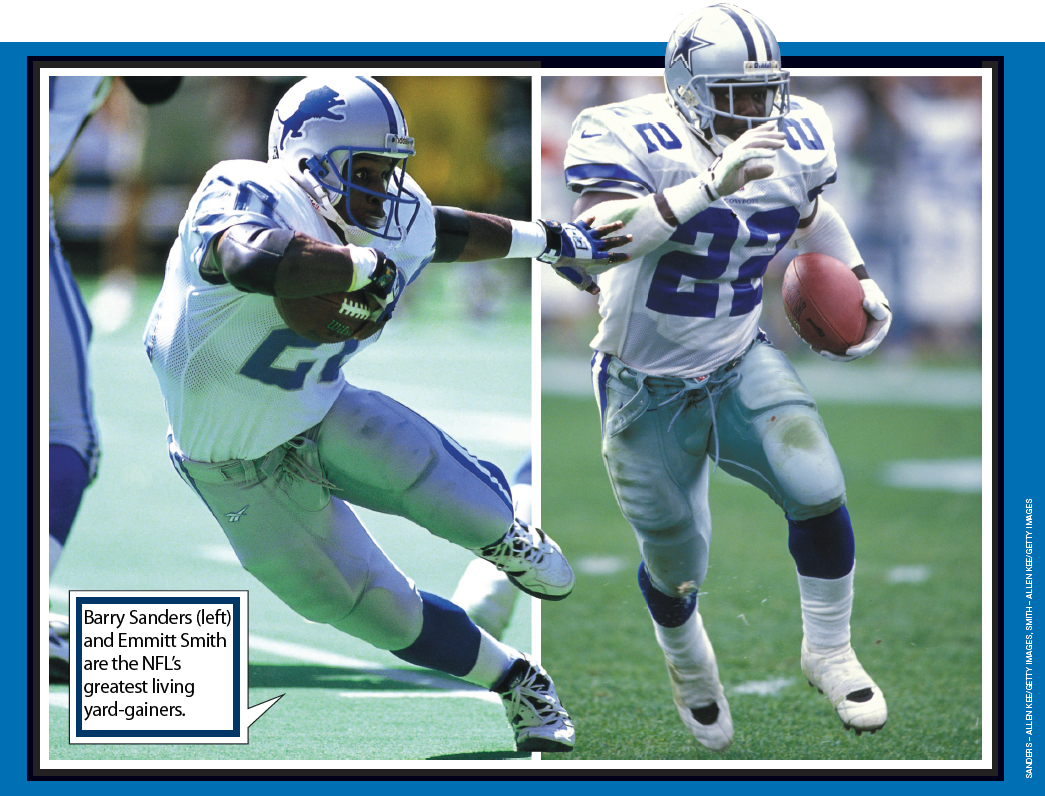

Football legends Barry Sanders and Emmitt Smith dominated defenses of the 1990s, accounting for a combined 19.1 miles of NFL rushing.

The two are the greatest living yard-gainers – known for finesse and power, records and mettle.

Their differences make them unique. Their successes make them stand together.

And here they are in Baltimore, signing autographs on the card show circuit at the 2012 National Sports Collectors Convention. Fans clog between ropes, carrying possessions fit for ink, hoping to leave with added value – along with a story about the time they met a legend.

Barry arrives first wearing soft colors, a short-sleeve shirt and shorts that would work well at a neighborhood block party.

Emmitt’s dressed in black, a long-sleeve shirt unbuttoned to the chest and matching pants, an outfit suited for dancing. Emmitt stands and smiles like he’s always on TV – another remnant from his turn on “Dancing With the Stars.” He won that show once. He’s on again this season.

To see the duo in person takes you back some place, the way your favorite band getting back together or another sequel to a long-running movie franchise might. You study their builds, and you wonder if they could still play football … especially Barry, since you never saw his skills erode with age.

With Emmitt, you try to forget when they did.

* * *

The labels that players earn during their careers don’t always carry, but they do in these cases. Barry remains elusive, as he was for defenders, as he has been since leaving the game in 1999. Sanders walked away from football with Walter Payton’s career rushing record within reach. Since that time he’s mostly stayed out of the spotlight. A card company had to track Barry down in Baltimore so he could sign some cards.

Emmitt, meanwhile, remains a star, just as he was when he played with one on his helmet. His ballroom dance TV show and that twinkle in his eyes tell us so.

For all their differences – and there are many – Sanders and Smith serve as the best representation of 1990s football, an era of sprawling card offerings and jaw-dropping highlight reels, fantasy backs before the fantasy boom.

The NFL hasn’t seen another rushing tandem quite like Emmitt and Barry. Between 1990 and 1997, either Smith or Sanders led the league in rushing each year – four titles for each.

Jim Brown, Eric Dickerson and O.J. Simpson are the only other running backs with four or more rushing titles, but they all played in different eras.

Following the Sanders/Smith Era, 12 different backs have led the league in rushing … in 14 years. Only LaDainian Tomlinson and Edgerrin James have won multiple rushing titles during that time.

Today’s top-tier running backs aren’t playing long enough to match Emmitt and Barry’s extended success, mutability that makes the duo’s gridiron greatness loom even larger.

Athletes of ungodly skill who compete at the same time often get grouped together. Russell and Chamberlain. Mantle and Mays. Ali and Frazier. Such is the case with Barry Sanders and Emmitt Smith. It’s not fair, exactly, but it’s our chance to contextualize greatness, our chance to explain something we may never see again.

Trophies and milestones

Barry Sanders made a lot of defenders grasp at air with his poetic, shifty running style. He also made a lot of people look foolish for doubting him.

One of 11 children born in a working-class Kansas family, Sanders was overlooked by most college recruiters due to his 5-foot-8 height. Too small, the critics said.

But Oklahoma State took a chance. Sanders backed up eventual Buffalo Bills great Thurman Thomas during his early college career.

His junior season, 1988, was all Barry – 2,628 rushing yards and 37 rushing touchdowns, both single-season major college records that still stand. Sanders garnered Heisman Trophy interest as the nation’s best player, a distinction he was quick to dismiss.

“Heisman Trophy? That is all good and fine and dandy and everything, but there’s more important things to consider on our team than that,” Sanders told the Dallas Morning News in 1988.

OSU’s quarterback at the time, current university head coach Mike Gundy, wanted to become Barry’s press agent to help him garner national attention.

“In the Bible, it says you are not supposed to gloat yourself, and he believes in that,” Gundy said.

So Sanders didn’t gloat. He didn’t attract the national TV audience of other Heisman hopefuls.

The statistics did the talking for him. He won the Heisman by a 2-to-1 margin over his closest competitor.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sH-IK2tTL4M[/youtube]

“I’m relieved, but I want it to be known individual goals aren’t as important to me as team goals,“ he said after his Heisman win. “It’s just been hard to see myself getting a lot of credit and watching (my teammates) get pushed back on a shelf.”

Sanders left Oklahoma State after that magical season, and he was selected by the Detroit Lions with the third pick in the 1989 NFL Draft.

Sanders didn’t take long to adjust to professional football, gaining 1,470 yards in his rookie season – only 10 yards less than league leader Christian Okoye.

He could have passed Okoye in the last game of the season. He decided not to. The milestone didn’t matter to him.

The changing hobby

Nineteen eighty-nine was a watershed year for football cards.

The hobby’s dark ages were dominated by Topps, which faced little card competition after the 1960s.

Rookie cards were an afterthought. Less demand and slower technology meant Dan Marino’s Rookie Card came in 1984, his second NFL season. Same with Jerry Rice, who debuted with the 49ers in 1985 but had to wait until the following season for his first pro card.

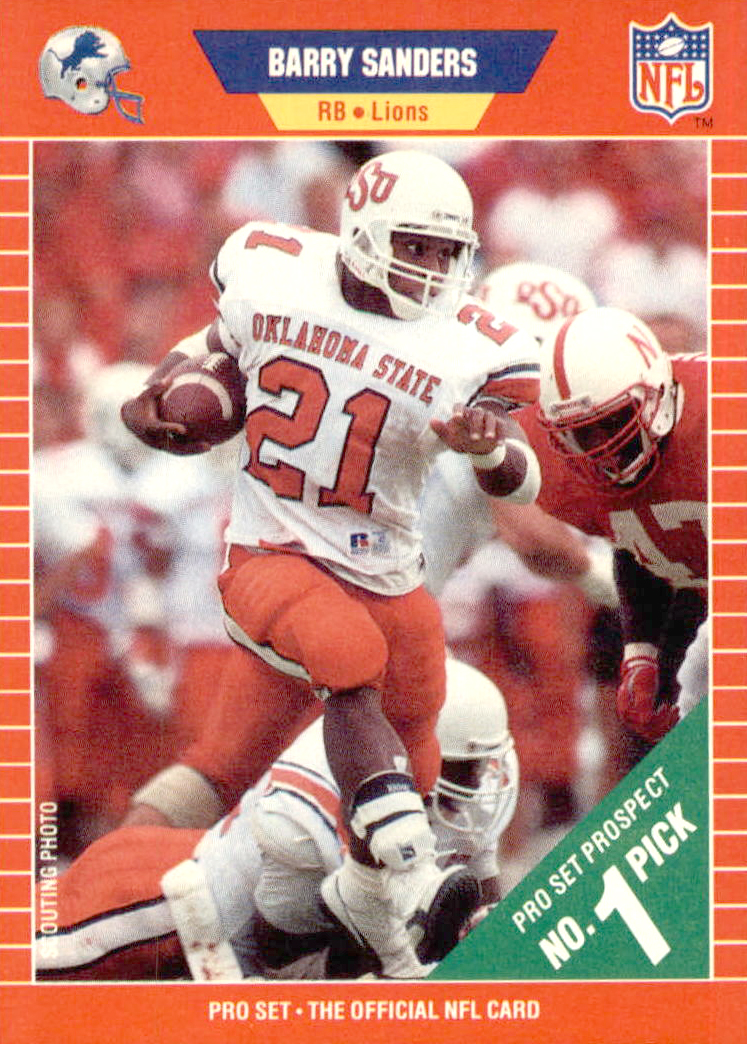

But in 1989, two new companies entered the fold – Pro Set and Score.

Pro Set, based in Dallas, partnered with the league to become the NFL’s official card company (whatever that means). The company’s billboards and TV ads generated collector interest.

John Frye, owner of Dollars & Cents Coins and Cards in Mesquite, Texas, originally couldn’t give away 1989 Score football cards due to the hype surrounding Pro Set.

“The 1989 Score product wasn’t selling, so I put it in the back room of the store,” Frye says.

Pro Set was so popular, it was the only card set listed in the ‘hot list’ for the first issue of Beckett Football Card Monthly, released December 1989.

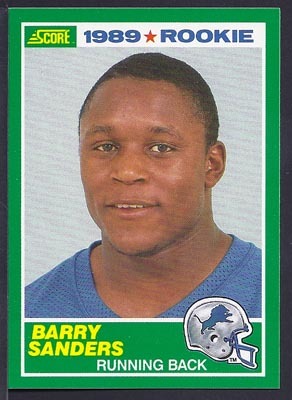

In that first magazine issue, Sanders’s Pro Set and Score Rookie Cards book for the same price: $2.00.

But Pro Set’s success would trigger its demise, with the company’s mass-production and numerous errors leading collectors to pursue less plentiful, more valuable products – especially 1989 Score, the cards that Frye initially couldn’t unload from his store.

Score’s first offering featured simple borders of green, blue and red, with heavy use of portraits and color on the card’s reverse.

The set centered around its rookies, the first looks at new players in pro attire. It didn’t hurt that 1989 offered one of the strongest rookie crops of all-time: Troy Aikman, Michael Irvin, Cris Carter. Thurman Thomas, Deion Sanders, Derrick Thomas, Andre Rison and Rod Woodson.

Card #257 in Score’s first football set shows a 21-year-old stud from Oklahoma State, a “slashing runner with marvelous balance and superb speed” who would transfix the game and transform the hobby.

That card remains Barry Sanders’s favorite from his playing days.

“At the time, you don’t know how far your career will go, how much success you’ll have, and your Rookie Card gains value based on what you accomplish,” Sanders said. “Many players have a Rookie Card, but it’s exciting to see people still collecting mine.”

People certainly still collect Barry Sanders’s Score Rookie Card, with mint-condition copies selling in the $20 range.

Scott Morse, owner of The Stadium, a card and collectibles store in Bay City, Michigan, says whenever his shop acquires a Sanders Score RC, it’s gone in a week or two.

“In terms of the Score Rookie Card, it was something to have,” Morse said. “Out here, that card was special.”

And those forgotten, un-sellable Score packs hidden in Frye’s store?

“I found those packs right around Christmas in 1990 or 1991, all the Score product that nobody wanted, and at that time it sold through the roof,” he said.

Rushing power

Like Sanders, Emmitt James Smith III came from a large family and faced criticism for his genetics.

One of seven children born in a working-class Florida family, Smith rushed for nearly 9,000 yards in high school.

But he wasn’t very tall – only 5-9 – and he wasn’t a speedster. No, power was Emmitt’s game, the power to break tackles and get into the open field. That power attracted recruiters.

Emmitt chose the University of Florida, and within two games he was named a starter. The freshman promptly rushed for 224 yards against Alabama, breaking Florida’s single-game rushing record – which was set in 1930.

“I hope I can get better,” Smith told reporters after the game. “I’ve just got a lot of desire.”

Smith did get better, gaining nearly 4,000 rushing yards in three seasons at Florida. Emmitt left college following his junior season, intent on NFL success.

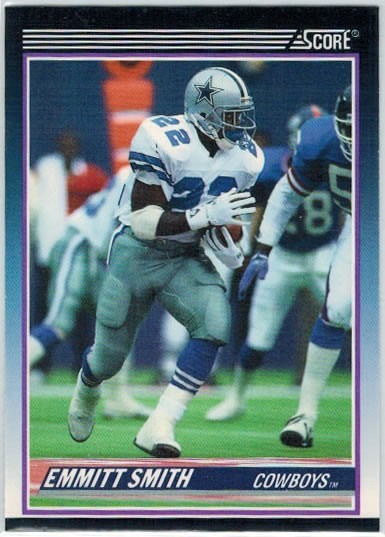

Again, the critics thought Smith was too slow and small, so he slipped to the Cowboys with the 17th pick in the 1990 draft. A holdout during training camp and the preseason kept Smith out of early card releases.

By the time his Rookie Cards appeared in late-season issues, he had rushed for 937 yards, invigorating a Cowboys fan base that had little to cheer about in preceding seasons and dispelling all those stupid ideas that he didn‘t have the right makeup for football success.

‘Pride thing’

Where Barry’s iconic Rookie Card became sought after over time, Emmitt’s most popular Rookie Card, 1990 Score Supplemental #101T, was valuable from its release.

“It’s his hardest rookie card to get, and the only way to get it is to break it out of the set,” Frye said. “1990 Fleer was the same, but for some reason that never really took off.”

Emmitt’s Score Supplemental card shows the rookie – “a runner with great moves, balance and toughness,” as he’s described on the reverse – carrying the ball against the rival New York Giants. The card is condition-sensitive due to the blue borders.

That #101T card also inspired Emmitt to study hobby trends.

“It was a pride thing to watch the card’s value go up,” Smith said.

And up the value went – from $40 in 1992 to $100 in the late 1990s. The card lists for $50 today.

“Your success on the field translates through collectors,” Smith said, “so I never minded that people benefited from the value of my cards.”

Beckett Football senior price guide analyst Dan Hitt said Barry and Emmitt’s most popular Rookie Cards profited from the perception that they were short-printed, at least compared to their Topps and Pro Set counterparts.

“Looking back on it 20 years later, we see that neither is short-printed when compared to nearly all of the more modern sets, so the hobby tends to divide up that large supply into smaller groups according to condition – that’s why grading them remains popular,” Hitt said.

“There is natural demand for both players, these are their most iconic Rookie Cards, and the supply is large enough to get a bump in value if you have a copy that grades out high.”

Zigging and zagging

It’s fitting that Sanders played for Detroit, a scrappy city known for machines that go very fast and very far. As far as running backs go, Barry was a machine – fluid and forceful, graceful and driven, city syncopation in his steps.

He zigged and zagged, his legs churning, his eyes darting, searching for glimmers of daylight.

Sometimes he ran backwards and sideways trying to avoid defenders. Those tactics didn’t always work. But when they did … The seasonal rushing totals remain staggering, even today. 1,470. 1,548. 1,883. 1,553.

Barry’s most memorable season came in 1997, when he rushed for 2,053 yards – with 2,000 of those yards coming in the season’s final 14 games. That stretch of 14 consecutive 100-yard performances remains a record.

After the final game of his MVP season, Barry’s offensive linemen carried him off the field.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W4ULOt5N6V4[/youtube]

The fact that Sanders accomplished so much while playing most of his career alongside mid-level talent – his teams had a 78-82 regular season record – makes his successes stand out.

Scott Morse, owner of The Stadium, a card shop in Bay City, Michigan, appreciates Sanders’s sportsmanship. He didn’t spike the ball. He didn’t complain. He didn’t get into trouble off the field. He stayed spiritually grounded.

“Barry Sanders was as classy an athlete as you can be,” Morse said. “His skills made you want to buy his cards, but the person he was did the same thing. I don’t think that can be lost, how special he is.”

Emmitt Zone

‘How ’bout them Cowboys?’

The early 1990s Dallas Cowboys were brash and bold, with enough swagger to embody the team’s long-running nickname, ‘America’s Team.’

America loved the Cowboys. America despised the Cowboys. America respected the Cowboys.

And leading the franchise was running back Emmitt Smith, along with quarterback Troy Aikman and wide receiver Michael Irvin. The three were nicknamed ‘The Triplets.’

Smith was the perfect star for Dallas, an all-purpose back who ate up yards, scored TDs by the bushel and did everything well – including receiving and blocking, a big-game back on the game’s biggest stage.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KvEXqWcouBg[/youtube]

Emmitt helped the Cowboys win Super Bowls in 1993, 1994 and 1996. Smith was named the MVP of Super Bowl XXVIII, a 30-13 victory against the Bills in which he rushed for 132 yards and two touchdowns.

All that winning breeds confidence, and Emmitt was known for ripping off his helmet after touchdowns. Emmitt Zone snap-back caps and letter jackets were popular. He appeared in a number of national commercials, pitching products such as Reebok and Right Guard (showing Emmitt at a dog show, of all places).

But Smith also parlayed his star power into community involvement and charitable efforts, aspects of his fame that stick with Frye.

“He’s still popular with fans,” Frye said. “You’ve never heard anything bad about him.”

Frye still keeps two binders of Emmitt Smith’s cards visible in his store, and every few days a collector will flip through the pages, scanning the cardboard memories.

Football card boom

Emmitt and Barry’s rushing dominance coincides with the football card boom.

After Score and Pro Set released their first sets in 1989, other companies jumped at the chance to produce league-licensed cards. Fleer and Action-Packed’s first full football card sets came in 1990.

The NFL Players Association could have licensed two additional companies that year, but decided not to for fear of flooding the market.

New companies followed in the years to come – Upper Deck, Pacific, Wild Card, SkyBox, Classic, Collector’s Edge, Playoff, Donruss and Score Board. Even NFL Properties released football cards, including a set called GameDay with cards that were more than 4 1/2 inches long, the same size as Topps’s famous 1965 ‘Tallboys’ set.

Sanders and Smith’s inclusion in products gave card companies something to offer collectors, the assurance of star power – and hopefully, but not always, value.

“I’m sure that stars such as Barry and Emmitt contributed to all the cards of the 1990s,” Morse said. “People wanted their cards, and they wanted different cards of them.”

During the height of their careers, Smith and Sanders both appeared on about 500 different cards each year. They’ve been featured on 225 cards together.

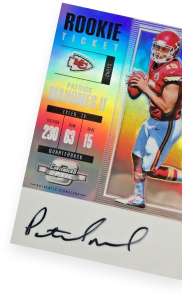

As the rushers’ careers unfolded, the cards became more sophisticated. Base and parallel-driven sets made way for short-prints, autographs and game-used gear.

The companies producing cards changed, also. Some of the companies folded. Others merged.

Only Topps and Panini currently produce NFL-licensed cards – but where companies of yesteryear released one or two sets annually, Topps and Panini offer dozens of card sets of varying price points, making 2012 a much different hobby climate than that of the 1980s or 1990s.

Today’s card releases are also rookie-driven. While Sanders has three Rookie Cards and Emmitt has five, 2011 rookie Cam Newton appears on 34 Rookie Cards. Some of those cards are worth hundreds – even thousands – of dollars. Some of Newton’s rookie cards are worth fast food lunch prices. Depends on the product and scarcity and added value.

All of that variety makes it unlikely that any of Newton’s rookie cards will match the enduring hobby presence of Barry or Emmitt’s iconic rookie issues.

“For current rookies, it’s hard to pick out one specific Rookie Card that’s more special than the others,“ Morse said. “The high-end brands are out of reach for many collectors.”

Reminders of childhood

The faded yellow box is buried in a stack of junk wax.

“All new II,” the flap reads, describing a promotion for a trip that expired two decades ago.

1990 Pro Set, Series 2. The heart of the football card boom. If you’re looking for value, this isn’t your first or best choice. But for sentimentality’s sake, Pro Set remains king.

1990 Pro Set, Series 2. The heart of the football card boom. If you’re looking for value, this isn’t your first or best choice. But for sentimentality’s sake, Pro Set remains king.

You rip into the plastic packs, looking for passing reminders of childhood. The first card shows Jerry Rice outrunning a defender. The next card shows Don Beebe going high to make the catch.

Reggie White in a three-point stance … Junior Seau, all smiles … Some of the cards strike different chords than they used to.

Some of the cards are ridiculous or awfully dated. “The NFL goes international: World League set for spring debut,” reads the front of card #788, an NFL newsreel.

Another newsreel card, “Team shop opens in Tokyo,” shows mascots and cheerleaders and a smiling Japanese boy.

Evidently Santa Claus was a head coach – says so on a “short-printed“ insert.

And then there’s Andre Rison’s “goof” card, signed on the reverse by Pro Set President Ludwell Denny. This might be the only time in sports card history that a company drew attention to an error. Usually you issue a corrected version or let the error stand, hoping the problem goes away.

Four Reggie Robys and three Paul Tagliabue Berlin Wall visits later, you strike pay dirt: 1990 Draft, First Round. Emmitt Smith, RB, Cowboys.

This Emmitt Rookie Card is worth $5 today. The card shows a side profile of Emmitt running against a wall of defenders, the ball cradled in his arm.

On the reverse – the mustache! The fade! For Smith, that card was issued half a lifetime ago. You can see it in his hair.

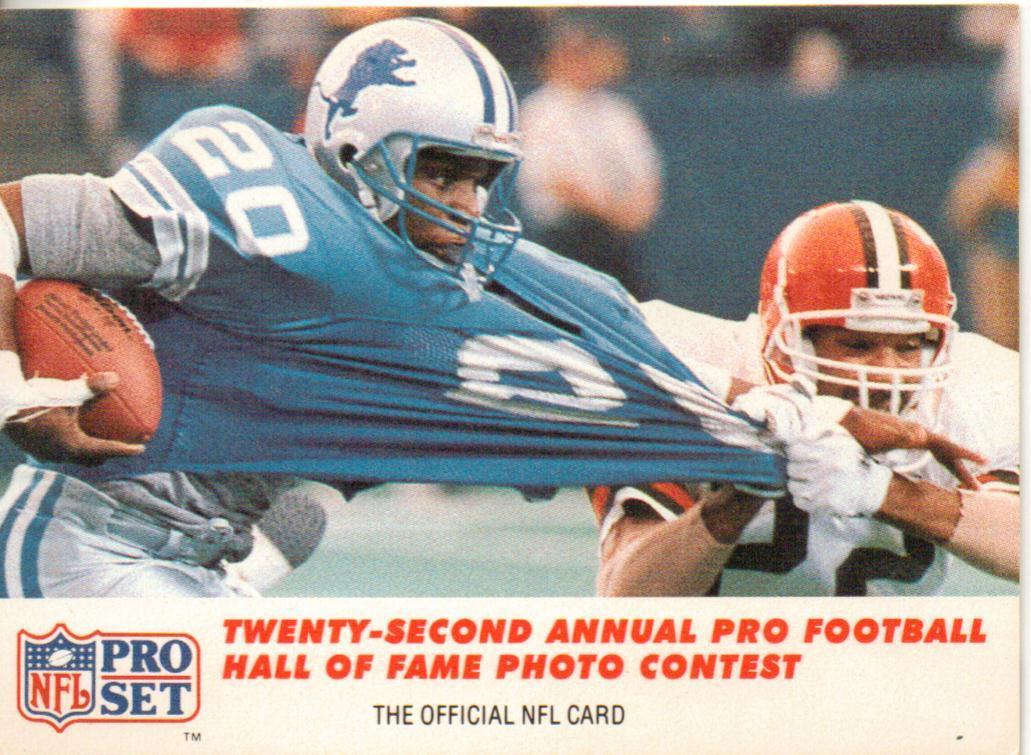

Another card from the set catches your eye, this one from the Hall of Fame photo contest subset. The photograph – taken on Thanksgiving, 1989 by Chris Boyd of UPI-Detroit – shows Browns safety Felix Wright trying in vain to tackle Barry Sanders.

Wright is gripping and yanking Barry’s jersey, stretching the fibers to their limit. He’s pulled the jersey about two feet in front of the runner’s body, to the point where Barry’s numbers ‘20’ are warped, disfigured by creases and protraction.

You’d expect Barry to have some reaction to Wright undressing him at midfield, but Barry’s face looks as though he’s just gotten the handoff. Stone cold, eyes ahead, teeth chewing his mouthpiece, cool as a cucumber.

Cardboard immortality

The beauty of sports cards is that they preserve moments, the slabs of cardboard serving as windows to yesterday.

Design and coloring and thickness and surfaces and smell all provide clues about the card‘s era, a mini-time capsule for constant reflection.

The cards were new at release, giving the players cardboard immortality. Barry will be forever smiling on his Score Rookie Card. Emmitt will be eternally running on his.

You get so used to seeing these collectible instants, that age’s true grip – a grim reminder on the sports legend autograph circuit – makes you pause.

Many of the past athletic champions are hunched and bald and sickly. Minds wander. Hair thins and grays and disappears. The yesterdays pile up.

Our favorite players’ aging serves as a mirror through which we measure our own growth.

You look for callbacks to provide a sense of normalcy. Seeing Baseball Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson makes you smile. He’s 53 now, but he still looks like he could slip on an Oakland Athletics jersey and swipe some bases.

Witnessing Emmitt and Barry in person evokes similar emotions. Both are still cut, still featuring similar dimensions to their youth.

Both look like they could rush for 1,000 yards today. You try to ignore the math and logic that says otherwise, how they’ve each been away from the game for roughly a decade.

But then you notice hints that things are different now. Barry’s face is fuller. Emmitt’s beard contains flecks of gray.

That’s what happens when people enter middle age. The running backs are 44 and 43 years old now.

Barry is a football dad. His son, Barry J. Sanders, is a freshman at Stanford University. Big Barry writes about little Barry online sometimes.

“Life is an adventure. This week my son graduates high school and starts his own adventures. So proud of you, BJ,” he wrote on Twitter in May.

Basking in the moment

Yes, Barry and Emmitt are on Twitter. Their postings provide glances into the gridiron greats’ lives. Golfing. Family responsibilities. Hobnobbing.

Barry’s page shows birthday cakes and EA Sports events, scooter rides and football-sized steaks.

Sanders wearing a cowboy hat makes you smile.

And there’s Barry and his son with pop/rockers Maroon 5. Barry is located in the center of the photo, the football legend draped in a beige trench coat, the bandmates’ smiles exposing star-struck inner children.

Emmitt, meanwhile, posts charity information and “Dancing with the Stars” updates. His Twitter photos show 20-year Cowboys reunions and White House visits.

He looks proud at his stepdaughter’s Sweet Sixteen party. Bow Wow was there.

Emmitt also enjoys sharing inspirational quotes.

“Emotions like fear and doubt have only as much power as you give them,” he wrote in August.

Barry and Emmitt took to Twitter after their afternoon signing autographs in Baltimore.

“Thank you Baltimore. That was a fun quickie,” Sanders wrote.

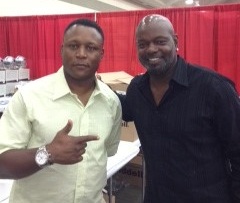

“Hanging with my man in Bmore today!” Smith wrote, posting a photo of the pair online. The photograph shows Barry and Emmitt together, arms around one another’s backs. Barry is pointing at Emmitt, a silver watch coiled around his wrist.

Emmitt’s wearing his megawatt smile, basking in the moment with an old friend.

Emmitt vs. Barry

While athletic contemporaries such as Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain were known for their head-to-head battles, the same can’t be said for Emmitt and Barry.

They only played four career games against each other.

Their teams weren’t natural rivals.

Since they both played on offense, they weren’t even on the field at the same time.

No, the rivalry was one of one-upsmanship, an arms race of leg strength, a battle born in stat columns and “NFL Primetime” clips.

When Emmitt’s Cowboys and Barry’s Lions faced off, Barry’s teams – yes, Barry’s teams – won three of those four meetings, including a 1992 playoff game that Detroit won 38-6 (Erik Kramer threw for 341 yards and three TDs in that game).

The most memorable match-up between the two backs came on a Monday night in September, 1994 – the national stage, two heavyweights swapping punches.

Smith rushed 29 times for 143 yards, including a fourth-quarter touchdown that sent the game into overtime. He also amassed 49 receiving yards.

But Sanders owned the night, dancing and jerking for 194 rushing yards, sloughing off would-be tacklers as if they were sweat beads. Barry’s Lions won on a field goal, 20-17.

That Monday Night Football game stood out to analyst Joe Theismann.

“There’s no question in my mind that game was personal,” Theismann told Beckett in 1996.

The tug-of-war continues between the competitors. Earlier this year, Emmitt and Barry engaged in a Twitter contest, a race to 150,000 followers.

Emmitt won. He was always better with those sorts of things.

Who’s better?

So who’s better: Emmitt Smith or Barry Sanders?

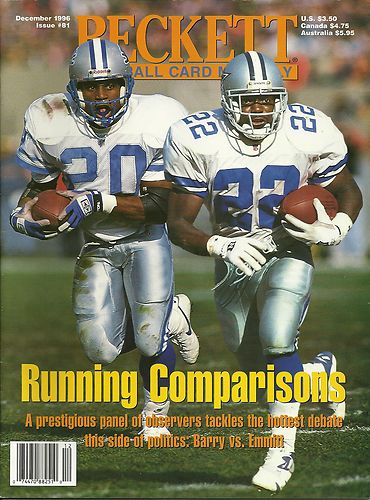

The debate is endless and futile, a circular conversation about talents and drawbacks involving two of the best running backs in NFL history. A 1996 Beckett Football Card Monthly cover story was devoted to the topic, with experts such as John Madden and Tom Jackson weighing in.

“(Sanders) is like Russian roulette – any play can be a touchdown,” Madden said at the time. “That’s the thing defensive players and coaches tell you. Sanders is unstoppable. He’s going to get yardage, and there’s not a thing you can do about it.”

Jackson considered Smith more of a power runner than Sanders.

“They’re actually different in subtle ways,” Jackson said. “Sanders makes guys miss in a flamboyant way, but Emmitt makes guys miss in close quarters, and for the purist, that’s just as artistic as Barry.”

Over 15 years later, and the debate continues – a debate that Smith is quick to dismiss.

“I don’t really take stock in the conversation over who’s better between me and Barry,” Smith said. “How do you measure greatness? By saying one player is better than another, it diminishes the other player’s accomplishments. Each player has different circumstances. Some athletes remain healthy throughout their careers, while other players suffer from injuries. Some athletes are lucky enough to play on great teams, while other teams don’t have as much success.”

Walking away

Barry Sanders was tired of losing.

The Lions had just compiled another 5-11 record, missing the playoffs again. The final game of that 1998 season, a 19-10 loss in rain-soaked Baltimore, caused Barry to openly sob.

“I was crying because I knew it was over,” Sanders said in his 2003 book, “Barry Sanders: Now You See Him … His Story in His Own Words.”

As the ensuing off-season progressed, Sanders became further disappointed by the team’s personnel moves. He stewed. He withdrew. He weighed his options.

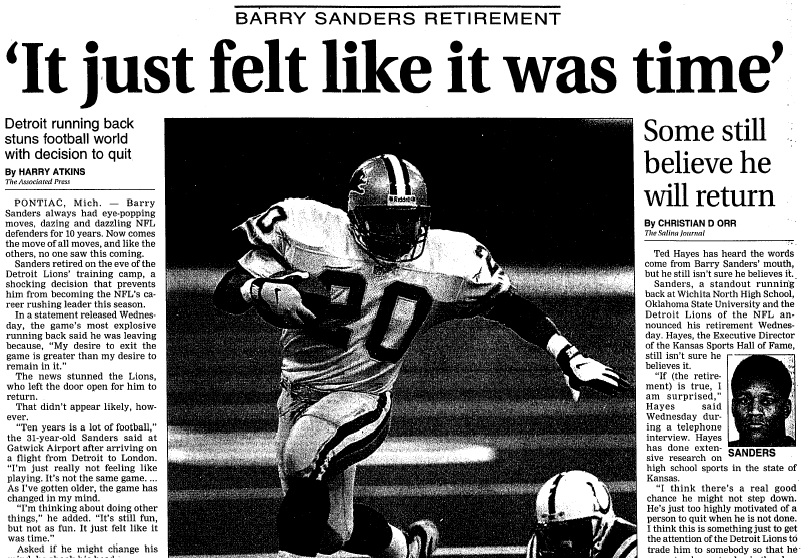

July of 1999. A new season approaching. And Barry, before heading to London, sent a fax to the Wichita Eagle, his hometown newspaper, announcing his retirement from football.

“My desire to exit the game is greater than my desire to remain in it,” Sanders wrote in the faxed statement. “I have searched my heart through and through and feel comfortable with this decision.”

Barry’s retirement sent shock waves through the league. Sanders was 31 years old at the time, still among the league’s top rushers and only 1,457 yards – about one season’s worth – behind Walter Payton for the all-time rushing record.

Fans and sportscasters wondered about Barry’s motives. Was he trying to get traded? Just another superstar on an ego trip?

People waited for Sanders to return to football, to put on the pads again.

He never did. The rusher known for his elusiveness retreated from the spotlight.

“Sometimes you just gotta move on. You can say it was too early, but I’d rather leave early than late,” Sanders said in a 2003 TV interview with the Ford Lions Report.

With Sanders out of the picture, Emmitt Smith became the most likely running back to eclipse Payton’s mark.

“It’s sad for the NFL because they’re losing one of the best backs in the game,” Smith told the Associated Press when Sanders retired. “I wish him well, I really do.”

The new leader

Emmitt Smith broke Payton’s all-time record on Oct. 27, 2002.

Fourth quarter against the Seahawks. A run to the left side. Emmitt skated through the line as the hole collapsed, then lunged forward on a second effort.

16,728 career yards – the new leader.

Smith’s teammates hugged him. Family and friends celebrated on the sidelines. Texas Stadium erupted. Blue and silver balloons rose to the rafters.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8bxK5Iybt4[/youtube]

That game was one of Smith’s last great moments in a Cowboys uniform. After a 5-11 finish in 2002, Dallas released their franchise’s record-breaking running back.

Emmitt Smith signed with the Arizona Cardinals – the Arizona Cardinals! – in March 2003.

John Frye, whose shop Dollars & Cents Coins and Cards is located near Dallas in Mesquite, Texas, said Emmitt experienced a dip in interest with local collectors after he left the Cowboys.

“The only time his popularity declined was after (Cowboys owner) Jerry Jones let him go, when he went to Arizona,” Frye said. “Even today, collectors come into the store sometimes looking for stuff from his Arizona days, because there’s not a lot out there.”

That first season in Cardinals red, injuries limited Smith to 256 rushing yards. He rushed for 937 yards in 2004. But by the end of the season, he was ready to call it a career. Emmitt signed a one-day contract with Dallas so he could retire a Cowboy.

“It’s been a tremendous ride, one that I’ve been very proud of. I think it’s been one that I’ve given everything that I possibly can both on and off the football field,” Smith said at his retirement press conference.

He finished with 18,355 career rushing yards, a record that still stands. The NFL’s active rushing leader, Rams running back Steven Jackson, entered the 2012 season less than halfway to Smith’s career rushing mark.

Getting the itch

After all these years, do the iconic running backs itch to play football again? You ask them the question to gauge their reactions.

“This time of year, I want someone to be putting the pads on, but it’s not for me anymore,” Sanders told Beckett Magazine.

Emmitt is less subtle.

“No, no, no, no, no,” he says, laughing. “No, no no.”

Dancing champ

Even retirement couldn’t diminish Emmitt’s star.

He became a broadcaster. He appeared in commercials. And he danced on national TV – live – something he did for 15 seasons in the NFL, but now with added flair and sophistication. Smith appeared on season three of “Dancing with the Stars” in 2006, bringing energy and polished masculinity to the show.

The new exposure was an adjustment for Emmitt.

“In the entertainment world, your face is a lot more visible. When I was on Dancing With the Stars, my face was on camera for 13 weeks in a row for hours at a time, where in sports you might only appear on camera like that during a post-game interview,” Smith told Beckett.

During the final episode of the DWTS season, Smith opened by dancing the samba to Stevie Wonder’s “Sir Duke,” his biceps bulging in a sleeveless green shirt.

Emmitt smiled, executed his steps and provided a solid frame for partner Cheryl Burke. Judge Bruno Tonioli picked up on Smith’s presence.

“You are blessed with such charm and charisma, you drive people crazy just with the twinkle of your eye,” Bruno said after Smith’s dance. “Hey, you got the twinkle in your toes to go with it.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LEoMfvdJJ4[/youtube]

Emmitt’s twinkles earned him three 10’s – a perfect 30. That night, the running back known for his titles won a mirror ball trophy as DWTS champion.

He’s back on the show again this fall, appearing on ‘Dancing With the Stars: All-Stars.’ His castmates are figure skaters and gymnasts and pop music singers. Emmitt still might be the biggest star of them all.

Football heroes

Barry Sanders remains the reluctant superstar, but some of his reserve has faded. The football legend is more visible now, if only in fleeting glimpses.

Sanders appeared in an intro for a Monday Night Football game last fall, speaking about the Lions over video footage of Detroit.

He also starred in an EA Sports commercial discussing his Heisman trophy, the award he was so ho-hum about in 1988. An outtakes video shows Barry annoying a photographer by continuing to extend his arm in the Heisman pose “I can’t work with this guy,” the photographer says, walking away. So Barry shrugs and hi-fives the trophy.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YeZDo1uJgE[/youtube]

Barry’s in the movies now, too. He played a football coach in the Kurt Russell film “Touchback.”

The movie cameos and video clips represent steps outside of Sanders’s shell. No, they’re not nationally-televised ballroom dance shows or phone commercials with 1980s sitcom character ALF. Barry isn’t Emmitt. Barry isn’t like the other celebrities.

Barry is … Barry.

And Emmitt is … Emmitt.

And as much as the two will always be grouped together, fans still appreciate their differences. So Barry and Emmitt supporters zig-zag through a maze of dividers, waiting for hours in Baltimore to meet their heroes.

A family approaches Smith’s table decked in Florida Gators gear, the parents and children proclaiming allegiance to Emmitt’s college team. Other fans are wearing Cowboys colors. On this August afternoon, the Emmitt Zone is still very real.

At Barry’s table, a boy and his father reach the front of the line. The boy looks to be 9 or 10 years old. He’s nervous, so he leans his head against his father’s chest.

The father puts his arm around the boy. It’s OK, son. Yes, it’s really him.

The boy wasn’t even old enough to watch Sanders play live, so his understandings of the running back come mostly from his father’s stories.

You imagine the father rummaging through an attic or closet to show his son his old football cards, the slabs of cardboard serving as windows to the yesterdays when Barry Sanders and Emmitt Smith ruled the football world.

Those days are gone now, but the cards remain – showing Barry and Emmitt forever smiling and eternally running, football immortality for two players who meant so much when you were young that you want to tell your children about them.

Dan Good has been a journalist for more than a decade. He currently works at the New York Post. You can email Dan here. Follow him on Twitter here.

Barry was twice the player that Emmitt was, and produced more with half the talent around.

great article

Had the honor of watching both players in their prime, as the article stated, Barry had the moves and looked so graceful when he ran. Emmitt was about the power, he would hit a hole and bang he was in the secondary running over Linerbacker and DB’s. Who was the best I don’t know, both were brillant and I thank them for playing the way they did. I still have my emmitt and barry rookies I got in 1989 andd 1990, every once in a while i pull thme and and think of the great games they played.

I always hated the cowboys and by extension emmitt smith but pound for pound there

was no running back tougher than smith.

yes the holes he was running through were wide enough to fit a car but you still gotta give him his due.

the guy played hurt and he ran hard.

all the time.

Barry Sanders 100%

Put Barry on the Cowboys roster and Emmitt on the Lions roster, who gets better and who gets worse?

Not trying to downplay Emmitt Smith’s ability but Barry is absolutely the better back.

So much nostalgia. Thank you for taking me back in time.